OUR DESIRE FOR NATURE

Park Royal, Singapore (photo from geekchicblogger.blogspot.com)

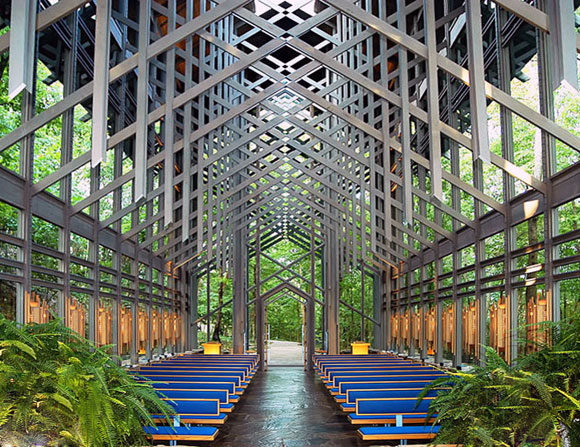

Biophilic Design refers to our instinctive association to nature and the resulting architecture that enhances our well-being. It has been suggested that Biophilic Design offers a healthy and productive existence, as well as happiness and joy.

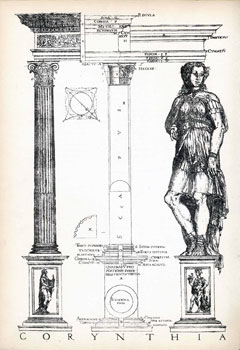

Goals for this prevalent design movement include the generous use of landscape inside and out, abundance of natural and artificial light, organic materials and textures, good indoor air quality and ventilation, and thermal and acoustic comfort—just to name a few. And our biophilia, meaning our love of nature, extends beyond architecture.

Monster companies, such as Amazon, Facebook and Google, use Biophilic Design to offer a healthier, happier and more productive work environment. This we know; so let’s expand our discussion of design and the creative arts, beyond the built environment.

From photography to vintage botanical prints, from classical painters to amateurs—capturing nature in two dimensions have driven artists for centuries.

Similarly, sculptors are drawn to the forces and mysteries of our natural environment. Here, installation artist/sculptor, Patrick Dougherty, combines his love of natural materials with his background as a carpenter.

Looking to the surrounding landscape for ideas, the world of fashion and glamour draws upon themes, patterns and colors in our natural world.

A popular icon of body art, flora/fauna is prevalent in the tattoo culture.

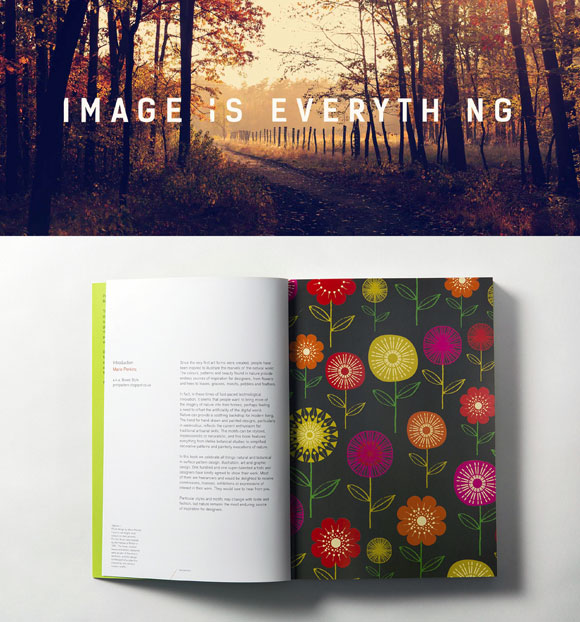

Similar to tattoos, the two-dimensional imagery of nature and its associated visual power provide graphic designers an infinite palette.

In baking a cake, rarely are these flowers real. They are usually just cream, butter and sugar. The origin of this longstanding decorating theme is unknown. Why does a wedding or birthday cake need to have flowers all over it? Why not birds and butterflies?

With his Sixth Symphony, known as the Pastoral Symphony, Beethoven choose to compose in a countryside setting, allowing the comforts of nature, its vibes and currents, to move him to write classical music. Other composers, such as Vivaldi, captured the abstract character of each season through melody, harmony and rhythm.

Whether a painting or a wedding cake, whether a building or a tattoo, Biophilia and biophilic design occupies our every day. In his 1984 book, Biophilia, Harvard professor, E.O. Wilson, introduced the concept, that we all have “the urge to affiliate with other forms of life.” Then he gave it a name, associated it with architecture and design, and we now have the moniker to label our innate love for nature: Biophilia.

Final note. Not everyone chooses biophilic design. In my article, White on White on White , we see that some do not seek a comfy house made of rustic wood and covered in vines. Rather, some individuals desire the modernity of a steel and glass, white house—ordered, abstract, simple, removed from the common traits found in our evolving nature and its living organisms.