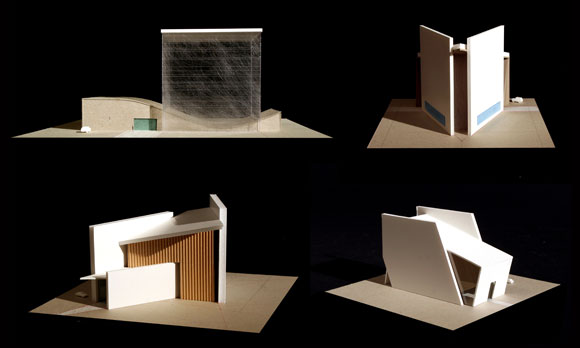

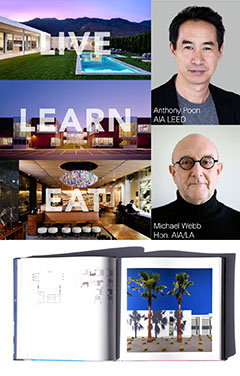

#134: LIVE LEARN EAT INTERVIEW PART 2 OF 2: RESTAURANTS BY POON DESIGN INC.

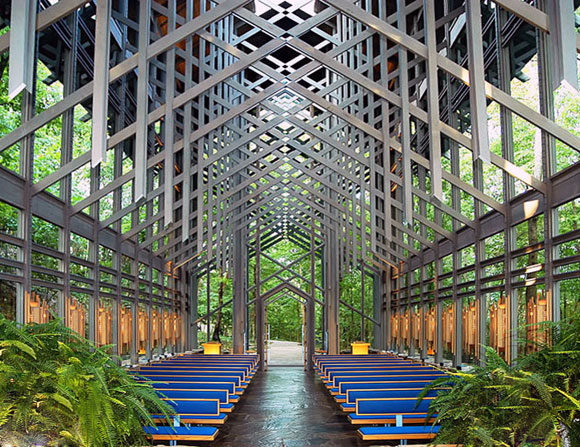

A wall of honed sandstone at Din Tai Fung, South Coast Plaza, Costa Mesa (photo by Gregg Segal)

(The complete Zoom interview is here, and part 1 on school design is here. The book, Live Learn Eat, is available at Amazon and your local retailers. Excerpts below.)

Michael Webb: Let’s finally get to restaurants. You’ve designed more than 50 varied examples, working on both generous and frugal budgets. Like schools, restaurants have to accommodate all their uses in the kitchen and dining area, and in between. How do you choreograph those movements?

Anthony Poon: That’s a good word, Michael, choreography.

All of us who go to restaurants spend time in the dining room, at the bar, or the outdoor patio. Behind the walls is a tremendous amount of activity. Roughly 50% of a floor plan goes to the back of house. It’s like a theater where one sees the play—sees what’s presented to them at the front of the stage—but they are not explicitly aware of all the activity going on behind stage, all the people running around. In the case of restaurants, there’s dozens of people in the kitchen with 30 cooktops, waiters dashing around, dishwashers, circulation moving everywhere—all while trying to present the most elegant dining experience for the user.

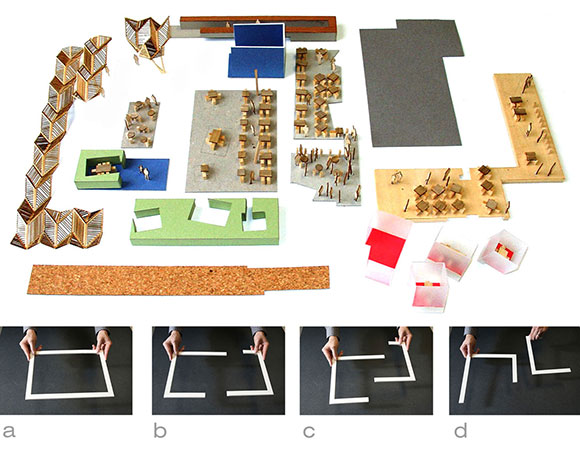

We choreograph all this—like a football coach with his green board, drawing X’s and O’s in chalkboard lines—to understand how a waiter needs to move from spot A to spot B, and not conflict with diners coming in for their nice anniversary dinner. There’s quite a lot of planning before we even get to choosing, for example, light fixtures and materials.

Michael: A lot of this is both physical, but also intangible. Restaurants define themselves by their cuisine, their service, and the atmosphere, the feel of the place, the acoustics, the way that everybody dresses. There are places that are super casual, others that are more formal. How do you bring all those things together in a seamless whole?

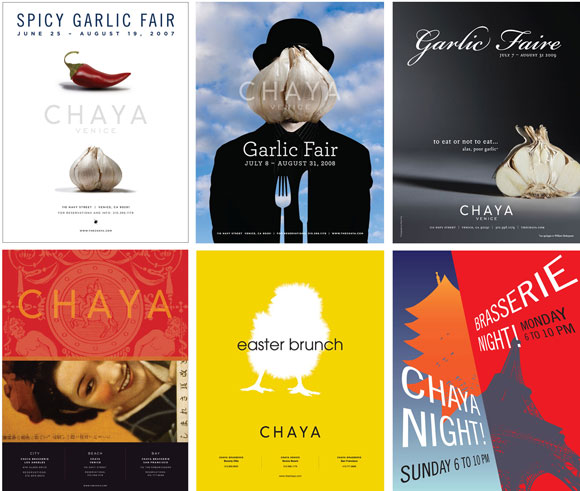

Anthony: We offer to our restaurants what we call comprehensive design. It starts with looking at the type of cuisine and the service model. It might be the handcrafted sandwiches of our client, Mendocino Farms. It could be the world famous dumplings of the Chinese restaurant, Din Tai Fung. We look to how their ideas can be represented in the architecture, but space-making goes far beyond architecture. For a lot of our restaurant clients, we have designed the architecture and the interior design, of course, but also bring in landscape ideas and lighting design. Also, we custom design furniture, and handle graphic design, the branding, website, and for some clients, even evaluate their uniform design.

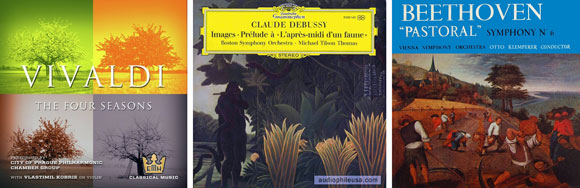

And then comes the music. Architecture is more than the experience you feel as you walk into a restaurant. As a musician, I believe that music is part of that architecture. I don’t know how many times I’ve been in a restaurant and the general manager has plopped in his iPod, and it’s just playing his playlist, a selection of music irrelevant to the style and flavor of the dining room.

At Poon Design, we feel that music should support the ideas of the chef. It’s the same way that some might say, “Let’s look at the way sunlight moves through the day, through the windows, through the restaurant.” We ask the same thing. What kind of music should be playing at lunchtime when the professionals arrive? At happy hour when everyone’s celebrating the end of an exhausting workday? What’s the appropriate music for fine dining? As a crowd winds down for late night drinks or dessert, what’s the kind of music for that? We think of music the same way we think of lighting design, the same way we pick the fabric for a banquette, or the wood stain for the tabletops. It’s all a comprehensive, integrated experience.

Just one last aspect, Michael, you’ve mentioned the acoustics. That plays into the quality of experience as well. I’m sure many of you have been to restaurants where you sit three feet from your friends, and you can barely hear their voices, because there’s such a loud ringing in the restaurant. Finally, you leave the restaurant after 90 minutes realizing your throat is sore from having yelled so much, and your ears are ringing from all the reverberation.

Part of the quality of the restaurant architecture is not just what it looks like but what it feels like—to all the senses. For music, that’s the ears. But we have to also bring our technical experience with acoustic engineering to control the sound, give a wonderful environment that is not just visual, but that is physical, that is aural.

Michael: I’d been told that restaurants actually welcome noise, because people drink more and eat faster, and therefore, the turnover and the profit is greater—that there is actually a kind of country movement against quiet acoustics of the kind that existed when there were carpets, upholstery, curtains, and all the old-fashioned things that we remember from long ago in restaurants. Now it’s all hard reverberant surfaces.

Anthony: All of our restaurants clients want their spaces to have a certain buzz—a kind of energy sounding through the room. No one wants to walk in and feel like it’s the university library where it’s too quiet. People go to restaurants for social contact, to be amongst a community of people, similarly to the difference between watching a movie at home on Netflix vs. going to a theater with a large group. There are people you might not even know, but that’s a certain valuable social experience.

Most restaurants will want music playing with a certain hum of sound, but it’s about controlling that, like playing the restaurant as if it’s an instrument. Like a musician, you tune it to the right feel. Some restaurants want a certain hyper energy during happy hour, where there’s loud music and a pulse. Other restaurants want that elegant, fine dining experience.

We start by looking to the restaurateur and asking them, what is your experience? Then we tune it to what they want as an identity, an acoustic identity. Just as a quick lesson, we explain to our clients what we call the ABC of acoustic design. A meaning absorb, B meaning block, and C meaning cover.

We choose materials to absorb what we want to absorb. You mentioned carpet. That’s a great material, but of course, very hard to maintain. There are so many other materials that could be used to absorb sound.

Block is about blocking out the sound no one wants to hear. No one wants to hear noises from the kitchen and washing dishes. So we want to block that as well as other back of house sounds—the restrooms, or the cars outside.

Cover is thinking about what sounds you want to cover and what you want to let in. If you’re on an outside patio on a busy street, you may want to cover the sound of cars honking, but you might want to pick up some of the energy of the city. You can cover unwanted noise with music. You can cover that with a fountain.

Michael: One of your star clients in Southern California was Din Tai Fung, who you mentioned earlier. The global chain that moved from its original place in Taiwan. Why do people line up for hours to get in? And what do they expect when they get in?

Anthony: People have waited several hours, even as much as five hours in the San Francisco location to get in. Visitors are expecting a lot, not just from the quality of the food, but also the experience, the service, and of course, the interior design and architecture. We’re proud to be the architect for the restaurant institution that the New York Times have named “one of the top 10 restaurants in the world.”

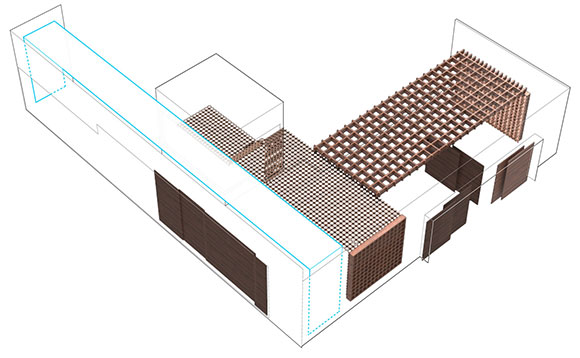

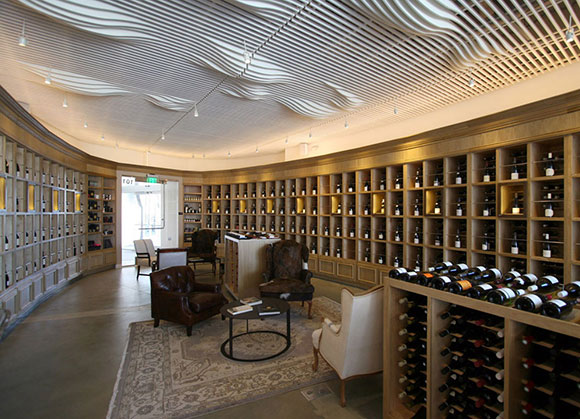

Design-wise, there were two main themes. The first: Din Tai Fung is famous for their dumplings, of which every day, they hand-make roughly between 50,000 to 100,000 dumplings per location. Folded carefully by hand, each fold represents a different artistic style and what the content is within the dumpling, releasing flavors and aromas as it goes into your mouth. We featured the dumpling-making as a theatrical element. As you enter, there is a large glass exhibition kitchen that presents all the dumpling makers as they’re making dumpling one by one, by hand. And the entire restaurant centers around this one activity, this one architectural feature. People come, even people not dining, just to sit there and watch this artistry in real time.

The second design aspect was this: Din Tai Fung is a traditional Chinese restaurant with cuisine and ideas from quite a legacy of family recipes. But this restaurant did not, in our minds, want to be a Chinese theme park, not a Chinese Disneyland. The clients were not interested in golden dragons, red silk cloths, phoenixes, and Chinese calligraphy. So we reinterpreted the legacy, both in aesthetics and in technique.

For example, we studied the traditional Asian, wood, privacy screens. Then we re-envisioned the traditional patterns, modernized them, and gave it a contemporary graphic feel. We took sheets of walnut plywood and water-jet cut our patterns, a new technique, or laser cut metal plates, then powder coated a finish. It’s a way of blending new construction techniques with traditional ideas, respecting Asian heritage and history, but also looking to the future.

Michael: Din Tai Fung can afford to do it in a very sophisticated way, but a lot of restaurateurs are working on a shoestring, and don’t want to burden themselves with a huge overhead before they proved themselves. Even some of the most important restaurants in L.A. has started in a very modest way. And when your clients have a tight budget, how do you make the best use of that?

Anthony: Most of our restaurant clients aren’t the big famous Michelin-rated ones. A a number of our clients have been small businesses—even a first restaurant cobbling together through family and friends, their first budget to launch a restaurant. We have to respect that, to know there are limits, and pick our design battles. We decide where best to spend money, being thoughtful and efficient in using dollars.

It also has to do with the conceptual approach. Mendocino Farms was one of our clients of which we’ve done one then several of their restaurants. We achieved a wonderful aesthetic through their interests in hand-crafted sandwiches within a kind of gastropub feel.

That gave us the opportunity to explore materials in a new way, to use industrial components, or maybe building materials right off the shelf. For example, plumbing parts were used to make the legs of a tabletop that looks cool and also adjustable in height. Or chalkboard paint on the walls with large chalk murals.

For the location near the Grove, each chandelier was made of chicken wire with 400 wooden clothes pins attached. It created a beautiful lighting effect, affordable too, and captures the aesthetic of that restaurant.

Michael: We’ve discussed the three themes of the monograph—homes, schools, and restaurants—but you have many other talents. You’re a classically trained pianist, an accomplished artist, published author, and your eight-person firm has tackled many other commissions from sacred spaces, to graphics, furniture and lighting design. How have you been able to achieve so much with such modest resources?

Anthony: I like to think of the metaphor of the jazz ensemble or maybe the small orchestra. We’re all highly trained and intelligent designers. We bring different unique talents, whether it’s interior design, lighting design, or construction expertise, maybe a graphics person. Everyone at Poon Design has multiple interests outside of the architecture field too, from photography to writing to studying history. We even had a literal rocket scientist on our staff for five years, who studied architecture at UCLA.

We assemble together all these talents and work organically. Our studio is a collaboration of everyone putting ideas together, bouncing off each other—similar to some of the ideas that jazz music represents, such as improvisation and spontaneity. I think it’s that kind of freedom and thinking that allows a smaller team to set forth some pretty big ideas.

Michael: What are your ambitions for the next decade, once we’re through the pandemic?

Anthony: We’re hoping to continue our design ambitions on a larger scale. We already work on projects from schools to restaurants, sacred structures, churches, mixed-use, and cultural projects. And it’s all for a sense of community, neighborhood, equality, and equity. We will continue what we do, but for a broader civic audience, and touch as many people as we can, as many participants of the public that want to engage good architecture and design.