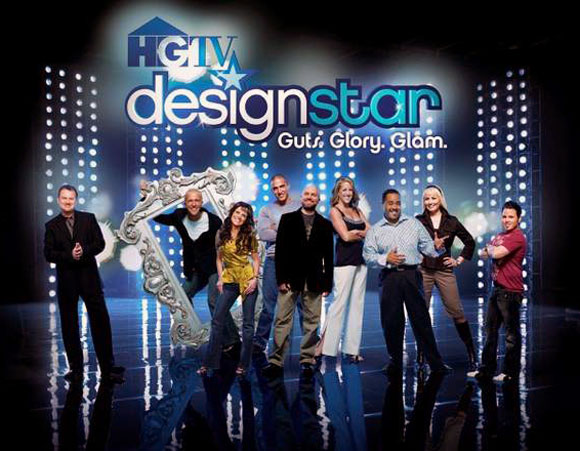

#114: SIX ICONOCLASTS: MARCHING TO THEIR OWN DRUM

The Factory, Catalonia, Spain, by Ricardo Bofill (photo from thisiscolossal.com)

There are the Usual Suspects, and we all know who they are. Featured on our magazine covers, these architects take home the big-name awards, are invited to international competitions, and cash in on their prestigious commissions. Then there are those creative minds that march to their own drum, exploring ideas that resound privately in their head. Rarely in the zeitgeist of the mainstream, these architects flourish in bizarre ways and have tremendous influence.

From Oklahoma to France, from California to Spain, from Alabama to New Mexico, these six artists did and do not follow the status quo. Instead, they sought solutions of ingenious personal expression— sometimes even unsettling forms and imagery.

BRUCE GOFF (1904 to 1983)

As I often enjoy doing with my design work, Goff too finds inspiration in music as well. He leans on Claude Debussy and Balinese music. He also happens to like seashells. Eclectic and unconventional, Goff’s work was sublimely organic—starkly original with never-before-seen forms and unusual materials. Regardless, a world-class institution like the Los Angeles County Museum of Art took a huge risk and scored big with hiring Goff.

RICARDO BOFILL (still in practice)

Bofill’s early works represented some of the most interesting explorations in Post-Modernism. With facile classical skills, this artist added fantasy and twisted plays of scale. For Bofill’s dystopia, see The Hunger Games: Mockingjay. Additional projects are other-worldly explorations into geometry and mind-bending repetition. His reconstruction of an abandoned cement factory transforms dilapidated structures into his personal residence and park, as well as offices for his architecture company (first image).

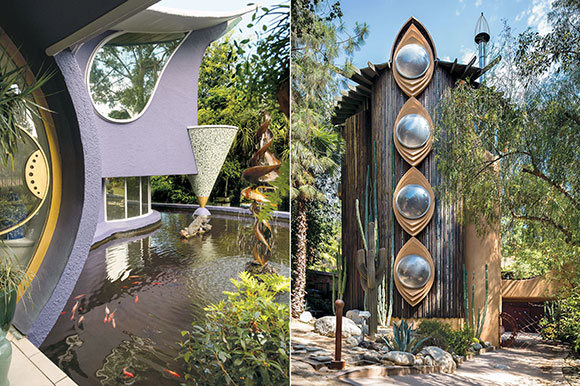

JOHN LAUTNER (1911 to 1994)

This Southern California architect captured the sunny optimism of the region. A student of Frank Lloyd Wright, Lautner similarly stretched the rules of structural engineering as well as spatial relationships. He pioneered new possibilities with poured-in-place, steel reinforced concrete. Lautner was a Mid-Century visionary of brave new worlds.

ANTONI GAUDI (1852 to 1926)

When I visited Gaudi’s work in Barcelona, it was only then that I realized that an architect can indeed build his fanciful visions that seem to appear from a hallucinatory fugue. Like a jazz musician, Gaudi improvises, experimenting with Gothic and Art Nouveau styles, taking engineering risks and aesthetic chances. 140 years later, the world is still dedicated to completing Gaudi’s design of the Sagrada Familia Church, an ambitious vision that was conceived before we even had the technology to execute the design.

SAMUEL MOCKBEE (1944 to 2001)

Look closely at the Lucy Carpet House. By its name, yes: Those are carpet tiles stacked up to make part of the exterior skin. The design used 72,000 worn carpet tiles held in compression by wood beams on top. And the smell, you might ask? The tiles were stored for seven years to prevent off-gassing. The multi-faceted red structure has a bedroom on top of a tornado shelter. Inventive, novel and philanthropic, Mockbee and his Rural Studio often worked with rural, disadvantaged communities.

BART PRINCE (still in practice)

Call it weird—rebellious too. Some would argue that Prince’s work was ugly or better yet grotesque. A colleague of Bruce Goff, Prince’s work was unprecedented and imaginative, whether you saw courageous splendor or awkward shapes. His architecture is a collision of myths, dreams and nightmares, laced with raw materials straight from the shelves of your local hardware store.

Ayn Rand promoted the Roark-ian ideal through her Objectivist view that “the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his only absolute.” Does this apply to my six iconoclastic architects above? Let’s just say that Individualism has it merits, as these architects value self-reliance in the creative process–as they cherish their artistic freedom