#131: GOOD OR BAD: THE SUBJECTIVITY OF DESIGN

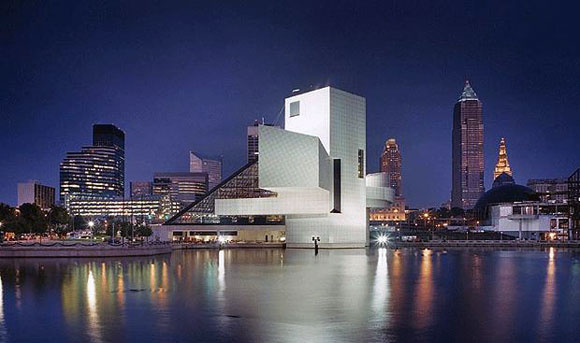

Notre-Dame de Paris, France: Universally considered as good architecture: (Photo by Leif Linding from Pixabay) San Francisco Marriott Marquis, California: “. . . always was and remains at the top of the ugly heap,” from gabriellafracchia.com (photo by Beyond My Ken)

It must be asked: What is good architecture? What is bad architecture?

A 3rd century B.C. Greek adage has become the seminal motto, “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” But who are these “beholders”? And is architecture subjective—to be determined on a case-by-case basis by whoever is beholden, whoever is the random casual visitor?

At a Princeton University panel, I once heard New York architect Peter Eisenman argue that there is, indeed, such a thing as good architecture and bad architecture. He cited one example, and I paraphrase, “If a stair is designed to go up, and the architect makes it to go down, then that is bad architecture.”

When a design is labeled timeless, that generally suggests something good—as in the architecture has stood the test of time. But timelessness is elusive. Someone might think of Mid-Century Modernism as timeless. Other would call it a fad. Another might argue for a classical Colonial style. And in turn, some would call it old fashion.

The American Institute of Architects bestows one project a year with their Twenty-Five Year Award. The AIA states, “The award is conferred on a building that has stood the test of time for 25-35 years and continues to set standards of excellence for its architectural design and significance.” And the winners of this annual award—from I.M. Pei’s pyramid in Paris (awarded in 2017) to Robert Venturi’s Post-Modern house for his mom in Philadelphia (awarded in 1989)—never look the same, meaning there is no explicit link between good and timelessness.

Over 2,000 years ago, the Roman architect Vitruvius gave us three rules defining good architecture:

- Firmatis, meaning durability: should stand up and remain in good condition,

- Utilitas, meaning utility: should function well, and

- Venustatis, meaning beauty: should delight people and enliven the human spirit.

But when I teach, how do I apply Virtruvius’ teachings when grading the work of my students? What is a B plus design vs. an A minus? If the students are designing a hypothetical city hall, I can recognize if the design complies with the required functions, i.e., enough offices, nice big lobby, required restrooms, and so on. But what about the intangibles? Does the work exude civic spirit? Does it stand proud acknowledging the history of the town, as well as look to its future?

Like with classical music, the performance is not good because the player has gotten all the notes right. The goodness comes from what is added after the notes, even in between the notes—such as the interpretation, the communication of something beyond the music.

Good architecture goes beyond its sticks and stones, steel and glass, beyond the number of classrooms in a school or seats in a theater. What is beyond is not up to the beholder or the architect, but things known as culture, progress, evolution, invention, wonder, humor, and amazement. Grasping all this or even some of this, if humanly possible for the architect, comprises good architecture.