MY FIFTEEN FAVE BUILDINGS

Dominus Winery, Yountville, Napa Valley, California (photo by Anthony Poon)

“Hey Anthony, what is your favorite building in the world?” I am often asked.

I might reply obnoxiously but with reason, “What is your favorite painting, favorite book or favorite ice cream?”

Just as there is no one favorite piece of music, there is no one favorite work of architecture. There are hundreds. But here I try. In this list of some of my favorites (in no particular order), I selected different building types and sizes—from a house to a parliament building, from a public plaza to a winery. I have also included a few of The Usual Suspects.

1: Can a design be both exquisitely silent and majestically heroic? Such is Louis Kahn’s 1982 National Parliament House in Dhaka.

2: In 1929, Mies van der Rohe contributed to the pioneering concept known as the Free Plan. Through a few carefully placed walls and columns, the Barcelona Pavilion gently and epically implies space and journey.

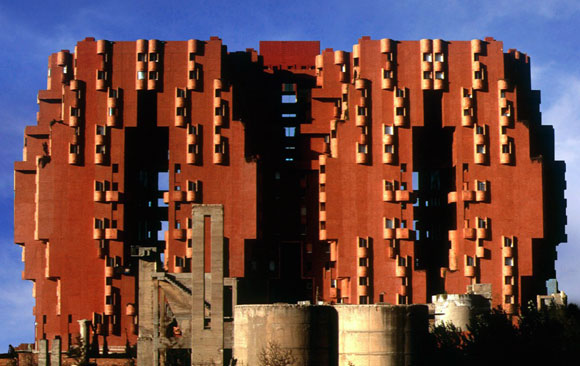

3: Before Ricard Bofill became fascinated with Postmodernism, he delved deep into his mind for fantastical dreamscapes. This 1975 apartment building known as Walden 7, in Sant Just Desvern, Spain, demonstrates what it means to be imaginative.

4. Situated over a station rail yard, Pinon and Vilaplana created a public square, transforming a blank space into one of Barcelona’s most powerful works of urban sculpture and place making, the Plaza de los Paises Catalanes.

5: Even in 1670, there were revolutionaries within a revolution. Baroque architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini twisted the classical world of pure geometry, and designed a chapel in the shape of an ellipse. Upon arriving inside Sant’Andrea al Quirinale in Rome, you are confronted by a twisted perspective.

6: The 2001 Wall House in The Netherlands was constructed three decades after the completed design, and a year after the death of architect John Hejduk. He juxtaposed Corbusian ideas with Cubism and Surrealism, offering one of the most formidable visions of a home.

7: During the design process for Maison Bordeaux in France, the client had a car accident that left him wheelchair bound. OMA quickly changed the 1998 design, transmuting the home office into a room size elevator, open on all four sides—where the three-story shaft is his library, art collection and office supplies.

8: In 1999, Rafael Moneo made two massive structures into leaning ethereal cubes of otherworldliness. For Spain’s Kursaal Congress Centre and Auditorium, Moneo explored prismatic volumes, glowing translucency, and double walls of rippled glass.

9: Some works, such as the Chapel Santa Maria degli Angeli, are pure poetry. Like the hand of God, architect Mario Botta placed this 1996 building gently in the Swiss mountains of Monte Tamaro.

10. It is not only astounding that Herzog & de Meuron wrapped an entire museum with dimpled, perforated, aging copper panels in 2005, but that these architects were able to convince the city of San Francisco that such a curious design idea would be the perfect addition to the beloved Golden Gate Park.

11: There is no limit to the extraordinary creativity of Catalan architect, Antonio Gaudi. Alongside studying the engineering of this ambitious cathedral by building an upside catenary model of stings and chains, Gaudi combined the Grotesque, Gothic and Art Nouveau, amongst many other influences. Since the start of construction of the Sagrada Familia church in 1882, the unfinished project is still underway in Barcelona.

12. Sometimes I think it is just fetishized retail design, but not at Rem Koolhaas’s 2001 Prada store in Manhattan. The street level floor wraps up then sweeps down to the lower level, bringing natural light to an otherwise dark space and creating the grand theater that is fashion.

13: At the early age of 26, Alvaro Siza created one of the most graceful compositions. More than a mere restaurant in Portugal, the Boa Nova Tea House of 1963 sits elegantly in its setting, as instinctively as the surrounding rock outcroppings.

14: Bernard Maybeck’s “temporary” monumental jewel of the 1915 World’s Fair still stands a century later, a romantic icon of San Francisco. With this Palace of Fine Arts, the “fictional ruin” expresses both an enduring melancholy of lost worlds and the ambition for new worlds to come.

15: Exploiting the elemental scenery in Napa Valley, California, Herzog & de Meuron formed the 1998 Dominus Winery with just some rocks placed in steel baskets. And that was the entire idea, the whole building.