#147: TRIBUTE: RICARDO BOFILL (1939-2022) AND THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE FANTASTICAL

La Mazanera, Calpe, Alicante, Spain (photo from ricarobofill.com)

A titan amongst us architects has left this world: Ricardo Bofill. In the zeitgeist of art, design, and individualism, it feels as if Atlas finally shrugged.

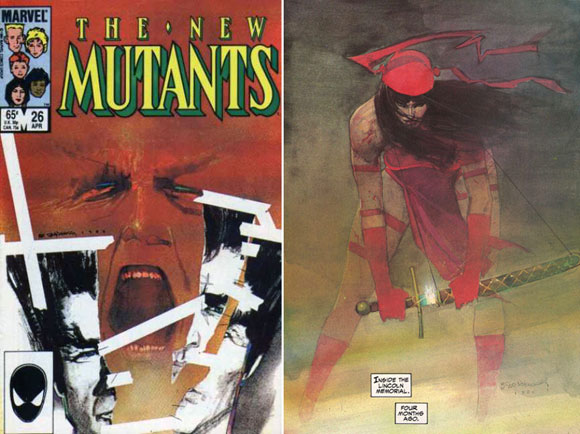

In 1986 New York City (here and here) I, a young architect bravely stomping the granite cobblestones of SoHo streets, came across one of those suspicious card tables selling random artifacts. The seller and his temporary setting, appearing ready to pack up and run in an instant, had me wonder if his goods were stolen, fake, or both.

A large coffee table book, 12 inches square and one-inch thick, stood out from the scatter of tarnished jewelry, etched dishware, and stacks of art books, old postcard, and dog-leafed magazines. My eye caught, Ricardo Bofill: Taller De Arquitectura, published by the then-giant Rizzoli. I did not know this architect, yet I was drawn to the cover image of a fantastical project (pictured above). I negotiated with the seller a price that fit the few crumpled dollars I had in my big boy pants.

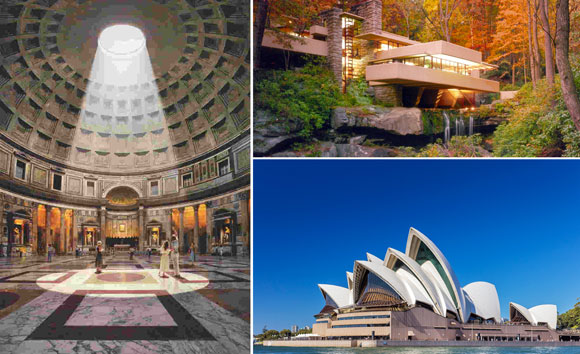

Back at my third-floor, walk-up, Chelsea studio, I devoured the architecture of Barcelona-born Ricardo Bofill—ambitious, utopian, revolutionary. Even controversial. Sometimes called dystopic. His global fame rose in the 70s and 80s with housing designs in France, several blocks large for neighborhoods like Marne-la-Valle. But much of his visionary creations in Spain preceded this recognition, and such earlier work established Bofill as an imaginary and puzzling thinker, akin to countryman, Antoni Gaudi.

His company name, Taller de Arquitectura, literally meant “architecture workshop.” This collaborative enclave of talent explored works of fantasy, concrete classicism, hyper Post-Modernism, organic forms, unprecedented sculptural forms and colors, and prefab concrete system construction—and did so beyond Spain and France, contributing to the urban fabric of the United States, Russia, India, Africa, and China.

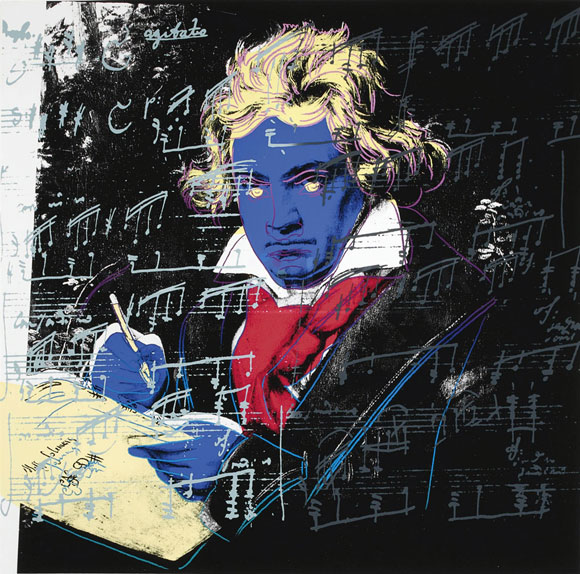

Much like “The Factory,” a culture and workplace of Andy Warhol’s making, Taller de Arquitectura was a cross disciplinary atelier comprising skills beyond architects, interior designers, and contractors, to include psychiatrists, philosophers, mathematicians, and poets. Akin to the makeup of his personnel, Bofill’s influences were eclectic: Wright, Barragan, Kahn, Aalto, Archigram, Japanese Metabolists, as well as artists like de Chirico, Escher, and Magritte. These lists of design references, geography, various philosophies, alongside his 1,000 completed projects indicate a man beyond measure.

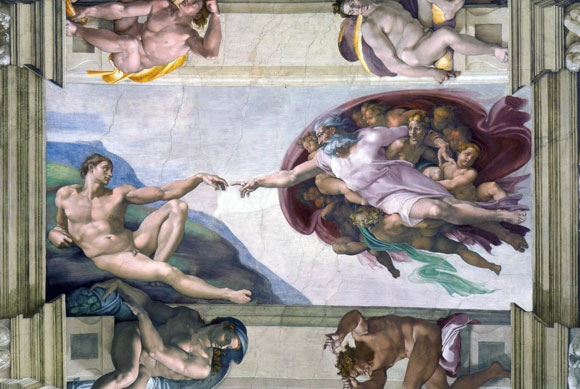

Bofill’s influence spanned across pop culture, films, TV shows, and video games, as his work is seen in movies such as The Hunger Games and in TV like Westworld and the recent Korean hit, Squid Game. In 1975, the President of France, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, labeled Bofill, “the greatest architect in the world,” later embellishing, “the greatest architect since Michelangelo.”

Few architects have established themselves as an artist with such heroic and audacious ideas—drawings that leap out from the pages of Bofill’s sketchbook into the context of major cities as iconic and colossal built work. His courage and creativity will be missed. Like his 30-silo cement factory turned headquarters and home, Ricard Bofill saw the world differently, shaped it to his will, and left monuments scattered around the globe for the rest of us to be humbled.

(photo from us.gestalten.com)