SYMMETRY AND THE LIKE

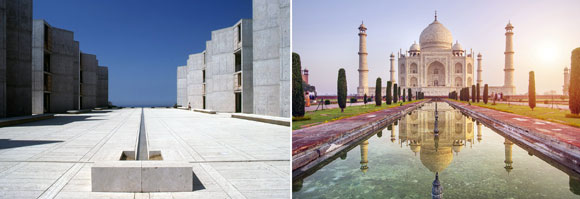

left: Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, California (photo from The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania/John Nicolais); right: Taj Mahal, Agra, India (photo by Getty Images

These images are what we commonly think of as symmetry. What you see on one side is mirrored on the other side. Classical architecture relied on symmetry for powerfully balanced compositions. But for a setting as peacefully symmetrical as the Taj Mahal, I find the architecture more interesting when accompanied by the asymmetry of life.

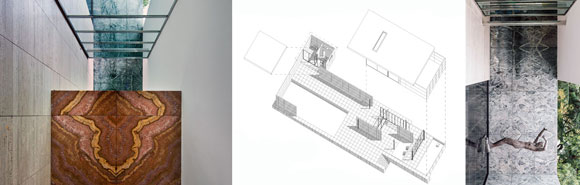

The 1929 Barcelona Pavilion, by Mies Van Der Rohe is hailed as one of the most significant contributions to the Modern architecture movement, with the pavilion’s Minimal walls and lines, blurring inside and outside. This structure is rarely mentioned in the conversations about symmetry. But that is only because we think that symmetry is when the right side is the same as the left side.

From what I learned in graduate school, I argue that symmetry can be such that the top half is the same as the bottom half. Top-and-bottom, not right-and-left.

In challenging traditional symmetry, implied symmetry offers complexity. Here, the balance of symmetry is only suggested, not at all exact. As the eye moves from the vertical axis of symmetry to the right and to the left, the design is forgiving, no longer relentlessly mirrored halves. An architectural feature on one side is not replicated on the other.

Beyond architecture, film director Peter Greenaway enjoyed applying symmetry as a cinematic device. As a young student of classical paintings, Greenaway employed symmetry not just in the set design, but with how the actors moved into the scene and located themselves. Akin to architecture, the result creates classical balance. But in movies, the experience is progressing over time and not as a static building. Greenaway delivers an experience that is harmonious but also disturbingly artificial. Could such compositions of people and objects exist in real life?

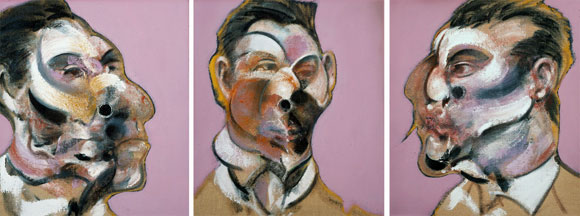

Symmetry in a person’s face is considered to be an underlying trait of beauty and attractiveness. A balanced composition of facial features supposedly delivers a fetching handsome appeal. But exact symmetry in one’s face is impossible. Consider one of Hollywood’s leading actors, often complimented as being good looking. Digitally creating a face using the left side and mirroring it, then as another composition, using the right side and mirroring it, you will see how even the handsome Brad Pitt is not symmetrical. As above, his face only implies symmetry.

These popular TV twins from HGTV exploit their identical look. But the outcome is like a Greenway scene— a contrived and awkward symmetry. Quite creepy actually, if you binge watch the show.

Lastly, this piano is symmetrical in exterior appearance. But inside, it is not. As with life, even things that strive for symmetry, harmony and balance, such things are often asymmetrical and lop-sided—and enjoyably so.