WINDOWS: “EYES TO THE SOUL”

A lot of traditional windows (photo by Andre Goncalves)

“Eyes are the window to the soul,” so said Shakespeare, Da Vinci and many other philosophical minds. Is it just a cliché? How about: Can one witness the soul of a building through its windows?

For light, view and air, windows are basically openings in a building’s exterior wall. Whether circular or rectilinear in shape, whether big or small in size, whether adorned with a classical frame or a minimal contemporary composition, windows are typically a clear and flat sheet of glass.

But today, technology accompanied by an architect’s vision (or ego) have transformed windows far beyond that sheet of glass.

Above and below, both Modern projects (by Rem Koolhaas of OMA) displayed are not shy in exhibiting its internal functions, activities and soul. In Old World architecture, stairs were often expressed primarily by a vertical massive form, such as a stone stair tower. Not so with this modern embassy. Its large abnormal corner window expresses the grand staircase of the upper floors, along with the embassy’s social energy.

This university center is less about windows in the traditional sense of openings in an exterior wall, but rather, these windows are the exterior wall. As giant, full height, edge-to-edge planes of glass, a viewer is greeted with a building eager to expose the full shape of the auditorium atop a student cafeteria. One could say that we have a “naked soul.”

Historically, glass was transparent and flat, and glass meant nothing more than that. With advances in fabrication and experimentation, the varying degrees of the glass transparency/translucency, as well as three-dimensional sculpting, offer new kinds of expression. The conventional idea of “frosted” glass that one might find in a residential bathroom, is surpassed by glass surfaces and forms of all sorts: fluted, mirrored, reeded, scored, and fritted—as well as concave, convex, and other such artistic explorations.

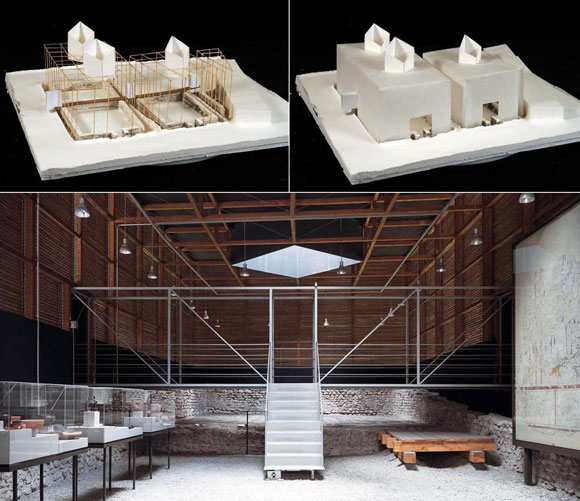

Another kind of window, though not often thought of as a conventional window, is the skylight. A skylight can be utilitarian, nothing more as it lets in natural light. Or a skylight can be sublime. With our metaphor of eyes to one’s soul, who looks into a skylight? Perhaps, the skylight as a window on the roof, is less about eyes looking in or out, but letting the external world grace the inside. Less about seeing a view from a living room window, as one example, a skylight lets the sky in, which is more about how one’s soul can be touched. As Zumthor acheived.

Windows are used for scale, to give a building’s facade a human element. Windows connect the inside to its surroundings, and vice versa. For most, windows are thought of as openings. And as “eyes to the soul,” these openings, outside of the world of architecture, can also be the opening weekend for a movie, the job opening, or a “window of opportunity.” As we look into these windows and openings, into these eyes, we observe souls of all sorts. Whether the souls are uplifted and wonderful, or challenged and confronted, it is this depth in life, as well as the architecture around us, that feeds the human spirit.