#157: “BE WATER, MY FRIEND”

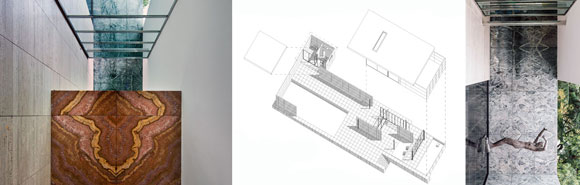

The Building on the Water, Huai’An City, Jiangsu Province, China, by Alvaro Siza and Carlos Castanheira (photo WZWX)

Throughout architecture, the element of water has played an impactful role—whether as a lead actor or the backdrop. Of the many ways water has been employed in design, five come to mind.

1. AS SETTING

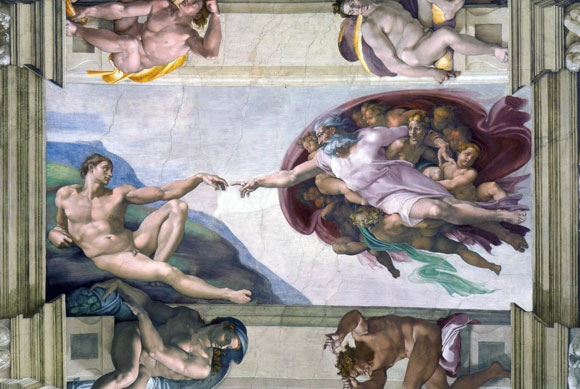

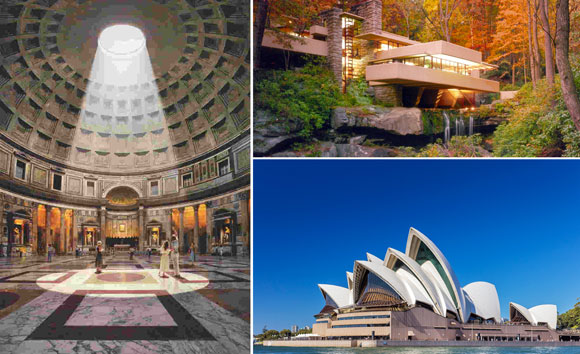

With some projects, water is the venue, the scenery. Such watery backgrounds are so significant, that one can’t imagine these projects without their liquid surroundings—as if a fish out of its water. Picture if you will the Sydney Opera House set within a desert or perhaps, the streets of New York City (here and here).

2. AS SOUND

Water is most often thought of as physical, as moisture we touch. But upon my pilgrimage to the famed Fallingwater, a home built over a waterfall, I learned of water not as wetness, but rather as sound. All the famous photographs of this structure did not prepare me for how loud, even deafening, the rush of aquatic was. Other such varied places, such as the tranquil fountains at Alhambra or the aggressive splashing at Embarcadero Plaza, the resonance of water in motion becomes the aural aspect of architecture.

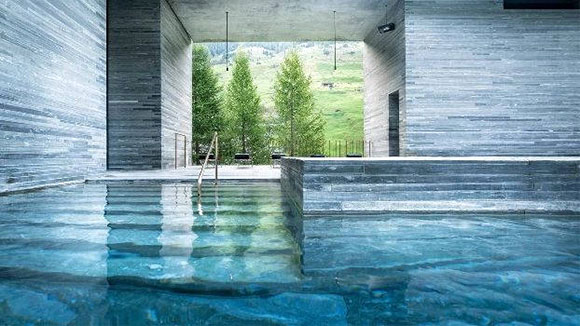

3. AS BUILDING MATERIAL

Akin to wood, stone, steel, or glass, water can also be employed as part of the physical palette of materials. The Blur Building uses water to be an “architecture of atmosphere,” stated the designers. Or what would Venice be if all the waterways were generically concrete and asphalt? At the Therme Baths, the water may be necessary for the functioning of this spa, but this element offers equal strength and boldness to the stone walls of local Valser Quartzite.

4. AS REFLECTION

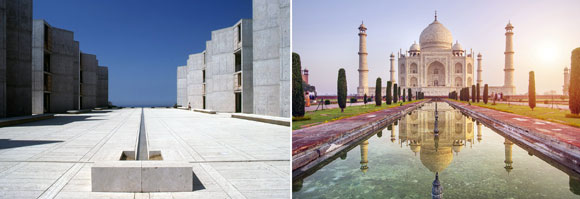

Water can provide a mirror-like surface, one of introspection, intrigue, and/or investigation. Architects have taken advantage of this quality to provide dramatic effects, whether furthering civic identify in Washington D.C., offering the perfect postcard of the Taj Mahal, or creating bizarre appeal in Spain. But the reflecting surface of water is not only fragile but sometimes temporary—shattered by a mere gust of wind or a ripple-causing pebble.

5. AS POETRY

Lastly, the mere use of water can transport a project to otherworldliness, transcending the design beyond that of a mere building. Water can offer a spirituality that approaches the sublime. Akin to poetry, the impact of water here is immeasurable and intangible, but long lasting.

I conclude with one of Bruce Lee’s most profound quote, “Empty your mind. Be formless, shapeless—like water. You put water into a cup, it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle, it becomes the bottle. You put it in a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Now water can flow, or it can crash. Be water, my friend.”

I conclude with one of Bruce Lee’s most profound quote, “Empty your mind. Be formless, shapeless—like water. You put water into a cup, it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle, it becomes the bottle. You put it in a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Now water can flow, or it can crash. Be water, my friend.”