#171: AI: BEWARE AND BEWILDERED

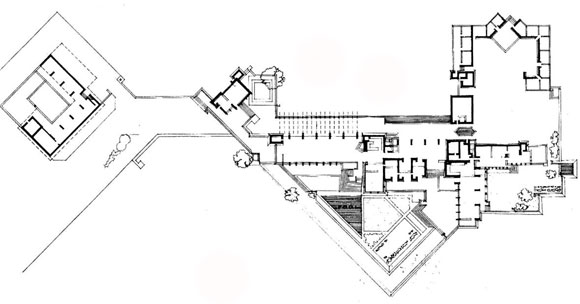

AI design by Manas Bhatia.

Do we need architects to create architecture? With artificial intelligence (“AI”) the answer is yes and no.

Years ago when writing my first book, I stumbled upon an AI app that could, with a click of the mouse, re-write my chapters in the “style of Hemmingway” or “style of Faulkner.” The results were not just entertaining, but convincing. But AI could only re-write my book, not write it from scratch. At least not back then.

Fast forward to today. AI can author screenplays, poetry, and entire novels. The question of whether the work is worthwhile remains the question, as AI delivers increasingly better results every day.

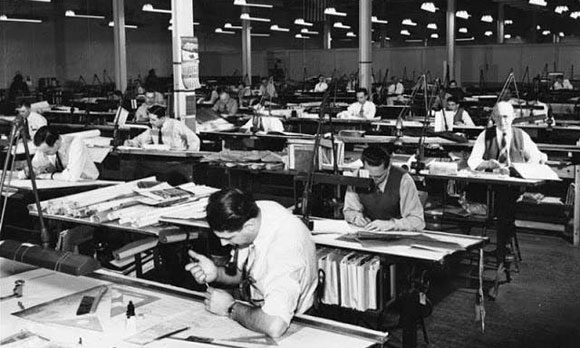

AI has been used in car design, healthcare, and manufacturing. Why not architecture? A decade ago, when AI invaded our creative turf, we responded defensively, “The AI results aren’t good at all” or “AI can’t replace the human hand and the personal touch I have with my clients.” But such reactions are shifting as the more open-minded see AI has yet another powerful tool to augment the work we do—tools like a T-square, AutoCAD, BIM, and 3D printing. So don’t worry: AI will replace you only if you let it.

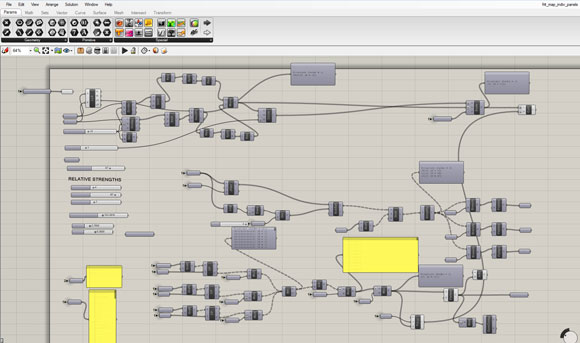

As glamorous and exciting as the design process is, much of architecture is analytical problem solving. With architecture as part science, AI can be ideal for analysis. Let the software perform code research, square footage analysis, cost estimating, quantity tracking, energy modeling, and parking counts.

Regarding the creative process, AI-software requires a facilitator, someone to prompt the program. If you ask AI to design an office space, the result may be a boring office with low ceilings and generic furniture. But if you ask AI to design “a creative office space with cathedral ceilings and Italian work stations,” the resulting design will be more inspired.

But are any of these results actually good? Sure, AI has speed and the capacity to generate options, but its explorations into new shapes and cinematic atmosphere, seems more like stage sets for a science fantasy flick than a livable engaging work of architecture—contrived and extreme vs. authentic and grounded.

At last year’s Colorado State Fair Fine Art Show, a controversy of AI made national headlines. For the digital art category, digital photographers/artists proudly submitted their pieces—painstakingly curated and fetishized. Yet an AI-generated work entitled, Théâtre D’opéra Spatial, took first place. But if there is no artist, shouldn’t this work be disqualified? No human hand was responsible for this striking work of art. Should a computer and its software be eligible to compete? Jason Allen, the “winning” programmer, came forward with no pretenses of having been the artist or author. Despite many questions and debates, the first prize ribbon stood, and a new controversial world of authorship has begun.

What are the ethics surrounding AI? Is there a morality to how and when AI should be used? As architects, we have a responsibility to “protect the health, safety, and welfare of the occupants.” In fact, we are licensed by the state to uphold our responsibilities, and held liable if we fail. Imagine designing a movie theater without the proper exits—and hundreds die in a fire.

So who is responsible for an AI-generated building design? The AI process is not flawless nor neutral, as one would hope science and technology to be. Also, AI lacks transparency. The machinations of AI are not comprehensible to us humans, as there might be biases, prejudices, and stereotypes. Who is accountable? Only our murky future holds the answers.