#113: ARCHITECTURE DESIGN COMPETITIONS: ARE THEY WORTH IT?

National Congress, Brasilia, Brazil (photo by Andrew Prokos)

The design competition is both an opportunity and a trap, both worthwhile and something from which to run away. Frequently, clients establish a competition where architects are invited to submit free ideas for the hopeful chance of being victorious, winning a commission of a lifetime, and immediately be thrown into the glorious spotlight of worldwide acclaim. But beware.

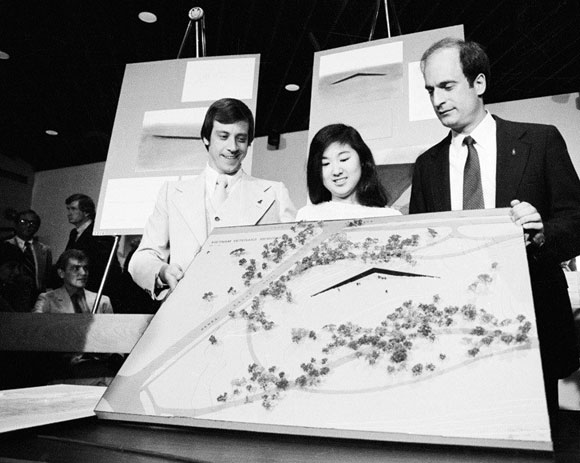

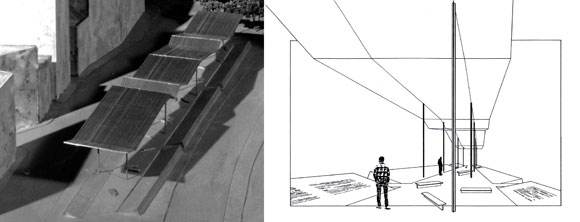

Most design fans know the incredible story of Maya Lin . At the young age of 21, she beat out a competitive field of international architects to take home the winning commission of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. Lin went from an unknown undergraduate student at Yale, to having designed one of the most beloved architectural monuments in history.

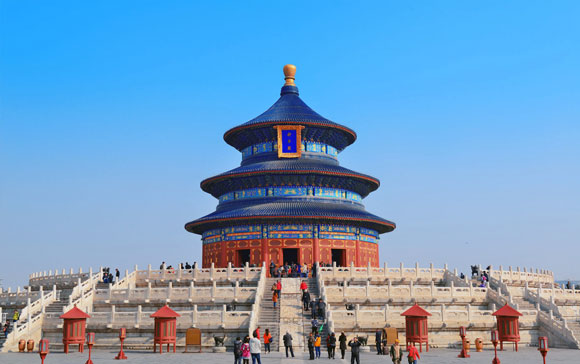

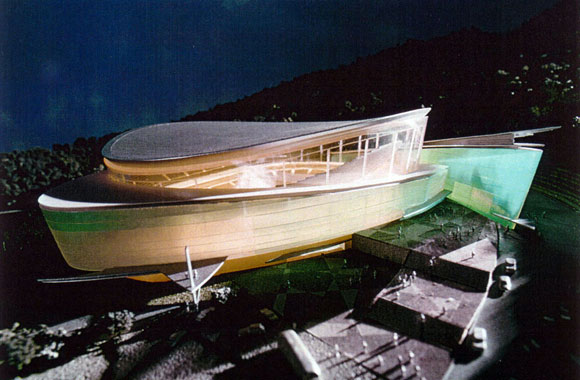

Even for veterans of our industry, the incredible impact of winning can resonate forever. Oscar Niemeyer organized the 1957 competition to design Brasilia in Brazil, and the victory to a team of designers changed lives forever, engraving in every architect’s mind an everlasting image of iconic architecture (photo at top). For me, I have entered a dozen design competitions. Some I won and some I lost. My first international victory was at 29, when I ungracefully stepped into the limelight by winning a worldwide design competition for the city of Hermosa Beach, California.

THE BAD

Most competitions are open to anyone and everyone. Note: The odds are nearly impossible. For Michael Arad’s win of the 9/11 Memorial in New York City, the odds were 1 in 5,201. Additionally, many competitions are looking for free work. Expect to gamble a lot of money and probably lose. I once worked at an architecture firm that spent nearly $500,000 in hopes of winning a contract to design a sports stadium. We lost.

There are invited competitions where the client creates a short list of architects, and each competitor is provided a monetary stipend to compete. As we all learned, this “good faith” payment is short of faith, never covering even a fraction of the time and resources invested in participating in the design competition.

A business colleague once asked me several questions to determine the value of entering an architectural competition.

– How many competitors?

– How much will you spend?

– What are the chances of winning?

– If you win, what are the chances of getting a fair contract with a good design fee?

– If you get a contract, what are the chances that the project will be built?

– If the project gets built, what are the chances that the project will be built the way you envisioned?

My colleague concluded that an architect’s interest in submitting work to a design competition was the stupidest thing he ever heard of.

THE GOOD

As mentioned, a win could jump start a young career or provide a breakthrough in a steady but slow career. No question—winning provides prestige, even if the project never gets built. At our studio, we joked that second place was our target. Then we would have some bragging rights alongside modest prize money, without the headache of trying to get a project built. (Fact: most competition winning entries do not get executed.)

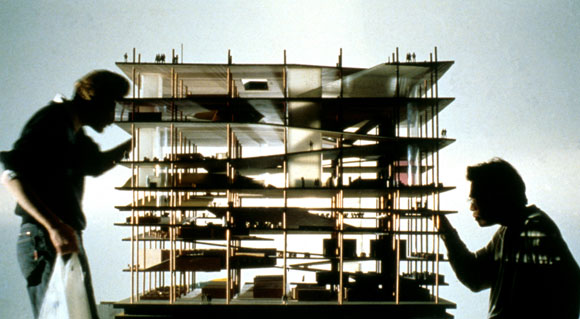

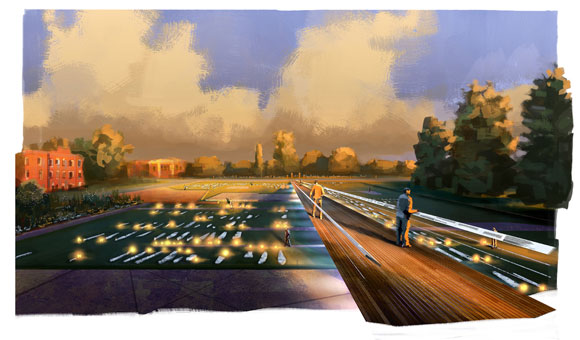

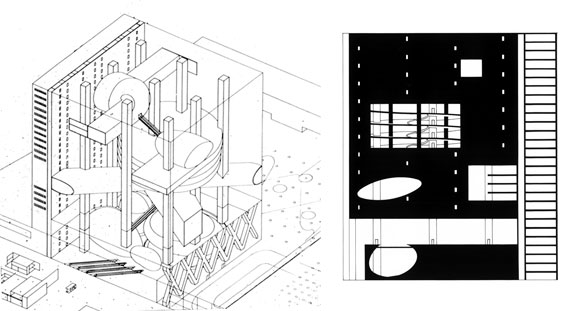

We like design competitions because they are a time for the team to put their heads together and play. Like a jazz ensemble, we brainstorm, improvise, test new ideas, research, experiment. We don’t worry about a client’s confusing and ever-changing desires, conflicting city codes, and budgets and schedules. Instead, we just dream up our most ambitious visions.

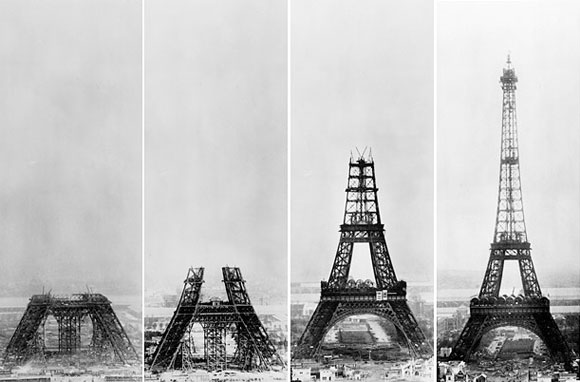

Design competition don’t just inspire a team of participating architects. The risks and results of competitions from winners to losers display the courage and creativity of the best minds in our industry. Even some of the losing entries or unbuilt works have changed the course of architecture.