#126: LIVE LEARN EAT INTERVIEW PART 1 OF 2: SCHOOLS BY POON DESIGN INC.

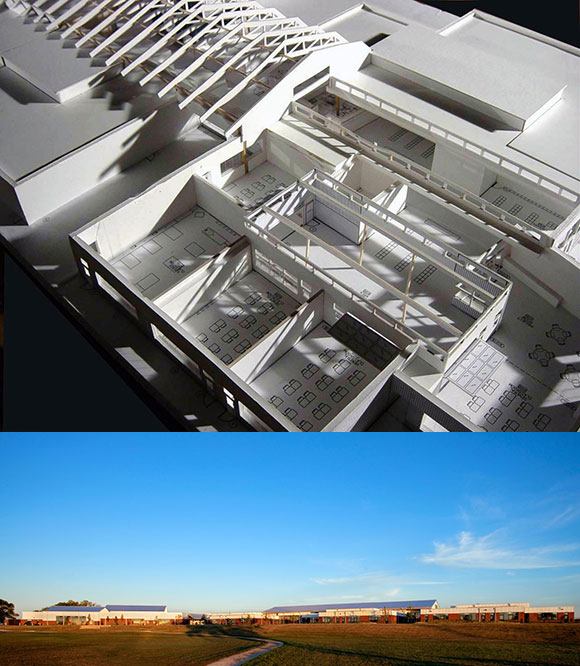

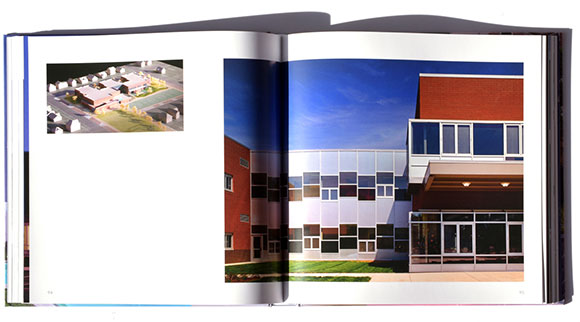

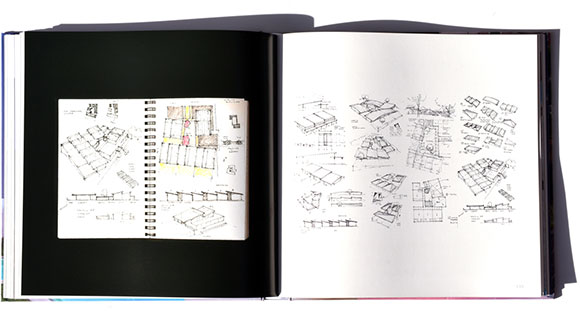

Pages of Live Learn Eat: Greenman Elementary School and Preschool, Aurora, Illinois, by Anthony Poon, A4E, and Cordogan, Clark & Associates (photo by Mark Ballogg)

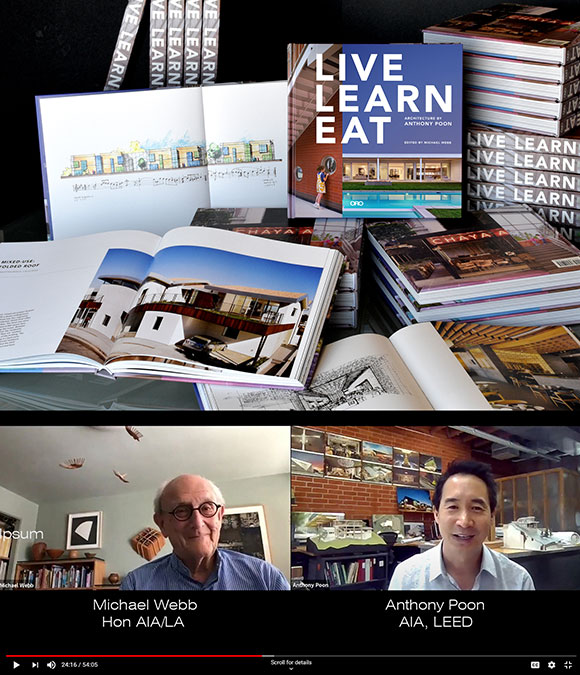

(The complete Zoom interview is here, and edited excerpts are below. The book, Live Learn Eat, is available at Amazon and your local retailers.)

Christine Anderson: Thank you for joining us today for a lively talk about a fabulous new book on the work of architect and artist, Anthony Poon, entitled Live Learn Eat. Our author, the noted architecture and design writer, Michael Webb, knows a good deal about living, learning, and eating—as he has traveled all over the world and has written a new memoir called Moving Around: A Lifetime of Wandering. Let’s take a deep dive into the design world of Anthony Poon.

Michael Webb: Yes, it’s true. I have spent half my life traveling abroad and writing about the best new architecture, but sometimes I make exciting discoveries in my own backyard. As a prime example, I give you Anthony Poon of Poon Design Inc., whom I describe as a pragmatic perfectionist, an architect who obsesses over the details, but has a firm grasp of function and value. I had the great pleasure of writing a monograph on Anthony, Live Learn Eat, which is being published this week. Live Learn Eat explores three typologies in which Poon has designed and excelled; houses, schools, and restaurants. If you think about it, living, learning, and eating are some of the most basic human activities, and typically they promote social interaction. Please join Anthony and I as we discuss his timely and timeless designs.

Let’s talk school design, which is a field in which you’ve excelled. You and a colleague (Gaylaird Christopher) master-planned an entire school district in Illinois, enhancing/rebuilding and/or designing from ground up 18 different schools. What did you learn from that?

Anthony Poon: Our approach to educational projects, PreK to 12 and higher education, focuses on the teachers and students. A lot of conventional school projects start with only the utilitarian program of how many classrooms, how many students in a classroom, square footages, how much storage do you get? Instead, we said, “Let’s look more closely at the educational curriculum and philosophy of each of these schools, and see how we can capture that in our architecture.”

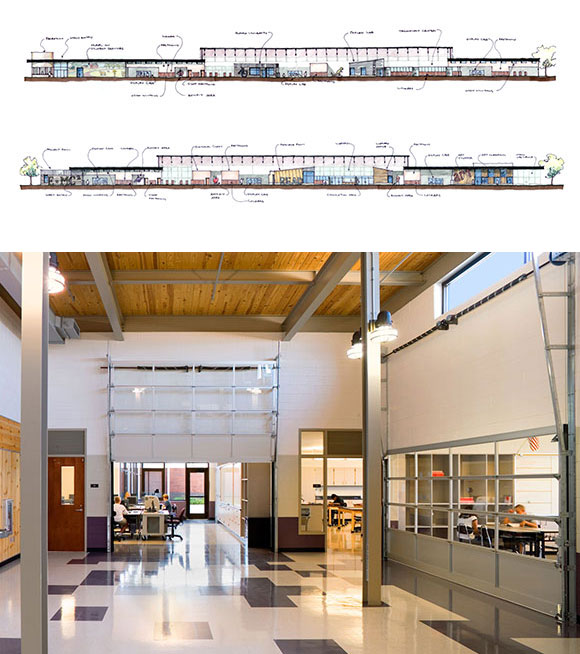

We think of a school design as an open textbook. We believe that every aspect of the building can teach. And we look to the teachers and ask, “How do you teach, and what can we do to support the way the students learn?” So, for example, if this is an elementary school that supports the idea of flexible co-teaching, we would design the classrooms with walls as movable partitions, where two or three classrooms can come together and learn as a group.

We’ve even used floor patterns to teach. For example, to introduce students as they approach the math wing in a high school, the flooring shows mathematical notations. Or as you walk down the hall to the music room, our floor design displays the music score of the high school fight song, which allows students to walk, skip on the notes, and actually hum them, as they walk into the music room. So, it’s looking at every opportunity in the architecture to say, “What are we teaching, how can these students learn, not just from their teachers, but from the actual building itself?”

Michael: Which again, introduces some basic issues of what makes a school building function well, for both the students and the teachers who have different needs, and perhaps parents who come to visit. But there’s always that complexity of interaction between different people, different groups, different students. Talk, if you will, about that, what is at the core of designing the school?

Anthony: It’s an ongoing topic, as we’re talking with some of our educational clients about the future of schools? Of course, there’s the proportion of the classroom and the number of students that would allow for certain physical distancing during this pandemic. But, what we are really looking at is the core ways that a school functions. For example, fresh air has always been relevant in the quality of a classroom. But over the years with air conditioning and mechanical systems, we’ve conditioned these classrooms so tightly that the idea of fresh air—the idea that a student can open up a window and let air in—doesn’t seem to be an option. With where schools are now, the idea of air, as it’s being studied by our office clients and restaurant clients too, is a critical aspect.

Just the way students move through a campus, whether it’s higher education or a preschool campus, is critical to their life at school. The school is the existence that students have as the first entry into being a civil servant and a part of a community outside of their home.

As they move through a school, we want to really map this out, not just in terms of the function and making sure they can all get off the bus and not get overcrowded at the front door and get to the classroom, but study where they socialize, where they form their network of communities. Think of it almost like a mini city. We’re sort of urban planning how people meet, how they react, how they respond to each other, or when necessary, just move along as efficiently as possible.

Michael: I imagine that most school boards are working on a very tight budget and that cost is a very critical factor. Unlike houses, schools get a lot of hard knocks. Students can be very destructive, kind of aggressive. And how do you balance those two things? You can’t use cheap materials, or finishes because they’re just going to look horrible in no time at all. Yet you have to stay within the set budgets.

Anthony: You mentioned our schools in the Chicago area (for example, Greenman Elementary School and Herget Middle School). The publicly funded budgets were reduced, very economical. And you’re right, Michael, if you asked anyone who runs a school, they’ll say it’s one of the most abused buildings. I think the kids haven’t yet learned to care for their environment. So our buildings need to be durable, affordable, and easy to maintain over the next five years, 10 years, even 50 years.

It’s about how you use materials and where you apply them. With one of our projects (Feather River Academy), for example, we used concrete block for the walls—very durable, indestructible actually, and extremely affordable. But if you use that kind of gray concrete block as it comes off the shelf, the school is going to look like a prison. We used different colors, different finishes from smooth and ground face to split face. Then created striking patterns. To soften the concrete block, we added planks of redwood, but up high on the wall, which allowed the wood to stand against anyone who’s looking to vandalize the surface.

Michael: Smaller firms like yours are getting squeezed out of this educational market by large firms. The same in the healthcare industry that specialize and, in fact, are grinding out very similar solutions for very different problems. Talk about the need for fresh thinking and what you can bring to a typology that a big firm is probably not going to.

Anthony: The words “expertise” or “experience” are some things that a lot of clients seek. As we pursue projects, a client might ask to see our last five completed high schools in the last five years, which is a difficult statistic to meet as a boutique design studio, maybe easier to meet if you’re a 500-person architectural corporation. But clients have to also be careful that “experience” from some companies may fall into the trap of a cookie cutter solution, where those architects too quickly go to their library of past design solutions and replicate them for new clients.

That’s the opposite of the way we approach things. We want all our schools, actually all our projects, to be as customized to our clients as possible: to understand each of our clients, what the mission statement is, to tell their story, to talk about their successes and even maybe some battle scars and lessons learned. We will make a project that is unique to every institution and every educational client that we’re working with. We look for clients that understand the value of design. If they are looking for a big firm to crank out a school design, one they’ve seen often and repeated in the district, Poon Design is not the right fit. We’re the one that wants to learn who you are, who your students are, and how your teachers teach. And we want to create something unique to you.