#155: WHETHER IT’S MUSIC, PAINTING, OR WRITING, ARCHITECT ANTHONY POON HAS A STORY TO TELL

“The interdisciplinary architect discusses his first novel, the relationship between architecture and music, and designing for everyone. Anthony Poon has a story to tell. Actually, he has many stories to tell—some in written form, others in the language of architecture, music, or painting.” So writes journalist Brian Libby for a recent article in Metropolis. Below are edited and abridged excerpts.

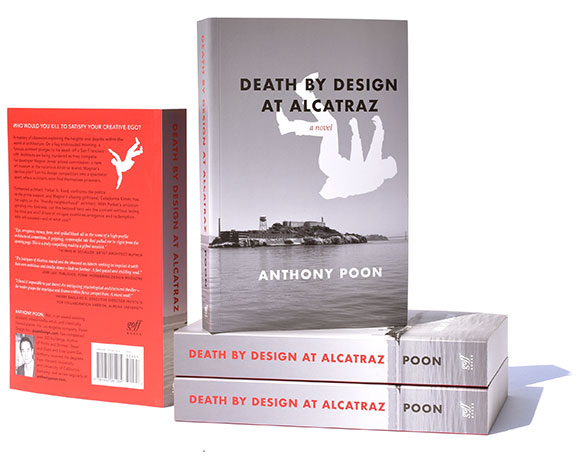

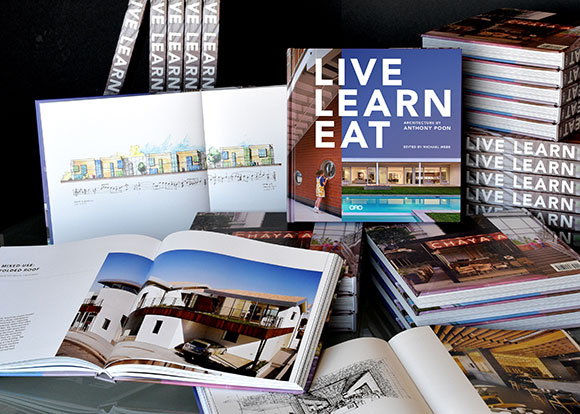

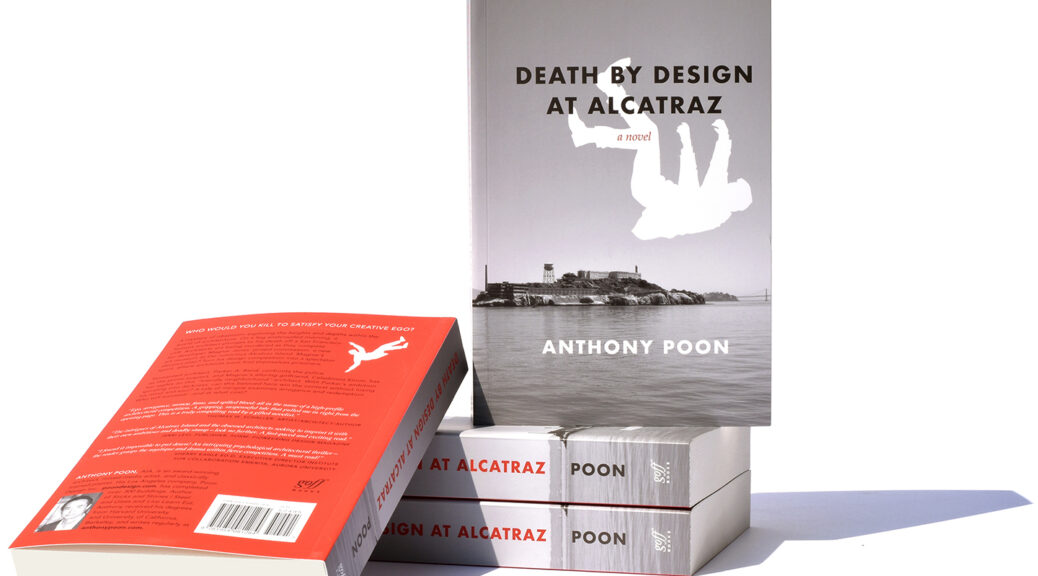

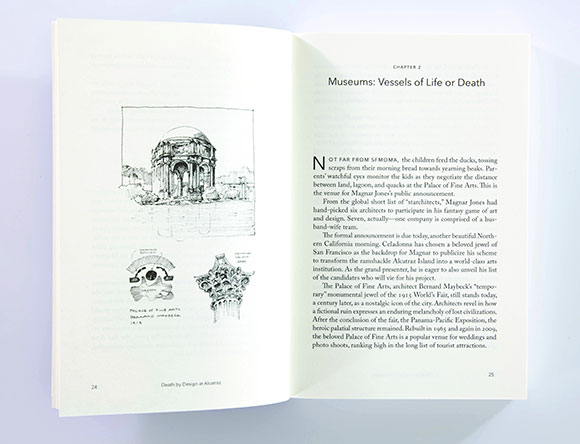

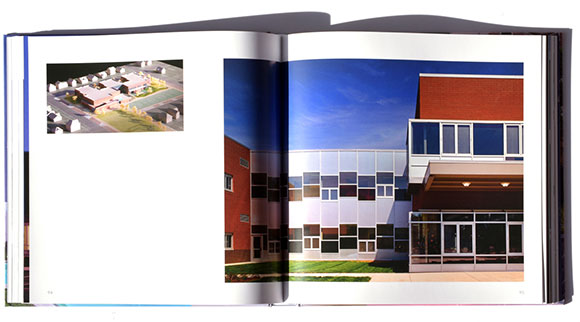

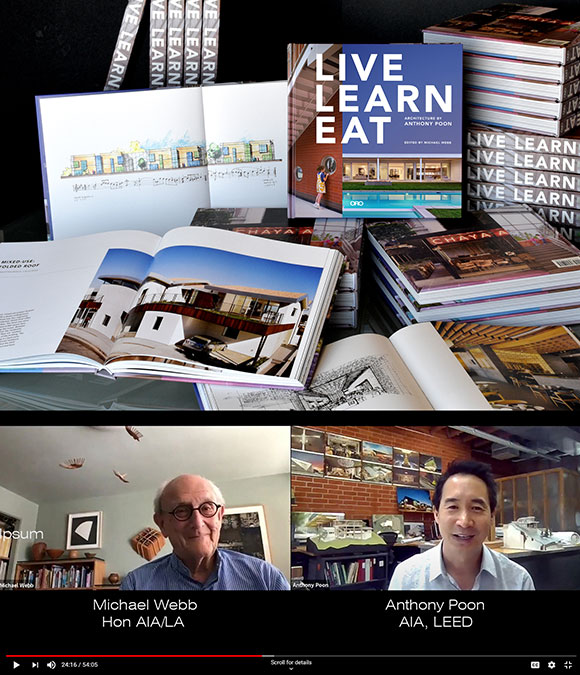

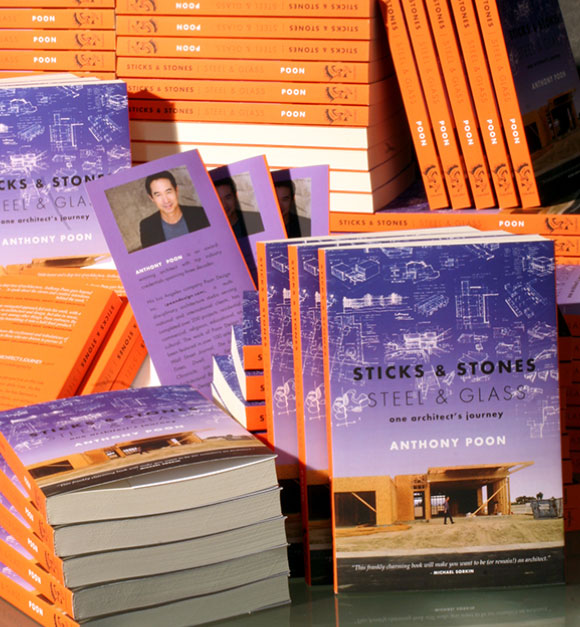

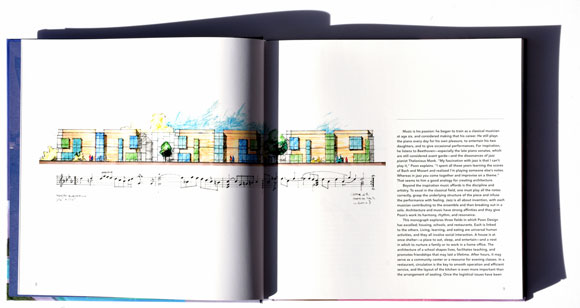

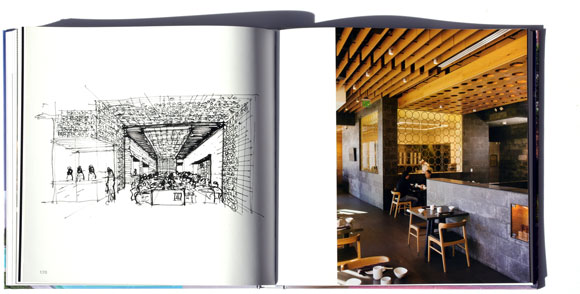

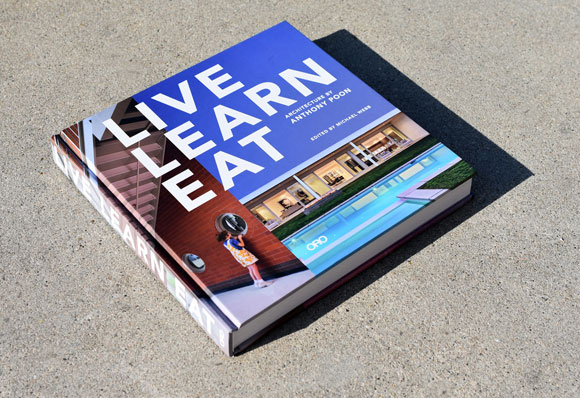

Brian Libby: Poon Design Inc. has completed over 300 projects, as chronicled in the 2020 book Live Learn Eat: Architecture by Anthony Poon. Earlier this year he was named to the American Institute of Architects’ College of Fellows, following national awards for educational, residential and restaurant designs. He’s also a certified Feng Shui practitioner, and recently released his debut mystery novel Death by Design at Alcatraz. Yet books are just one of Poon’s passions. He’s also a mixed-media artist and with a master’s degree in architecture. Poon trained even longer—from the age of six—to be a concert pianist. In 1987, after earning a magna cum laude in architecture and music from the University of California Berkeley, he had to decide between applying to The Julliard School and Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, ultimately choosing the latter.”

The question of rigid composition versus improvising relates to being a pianist. Could you talk about that?

Anthony Poon: Growing up, my training was classical music. It’s this process of aiming for perfection, a flawless performance. Playing a piano sonata—there are a hundred thousand notes, and you’ve got to hit them all correctly. If I got one note off, my piano teacher would say, “That whole performance is ruined.” But I got interested in something beyond technical proficiency. You’ve got to be able to add a voice, a story. I eventually learned about jazz. It blew my mind that these pianists would just sit at the keyboard and make things up.

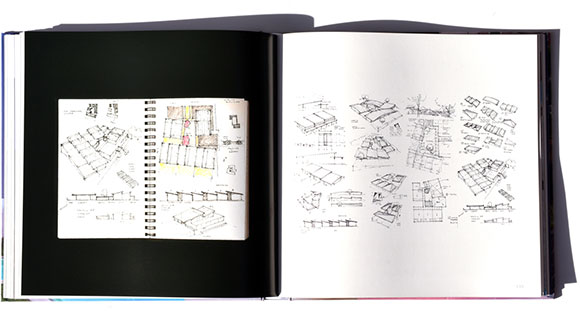

Brian: Your thesis at Harvard was about how jazz improvisation informs the architecture process. What did you learn?

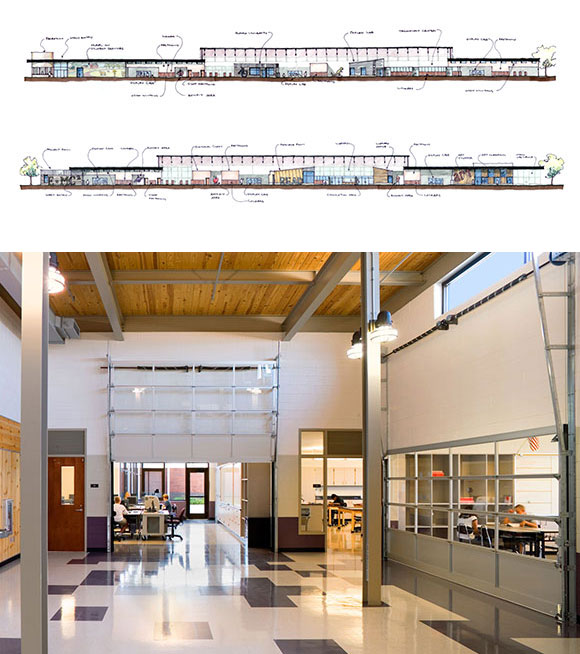

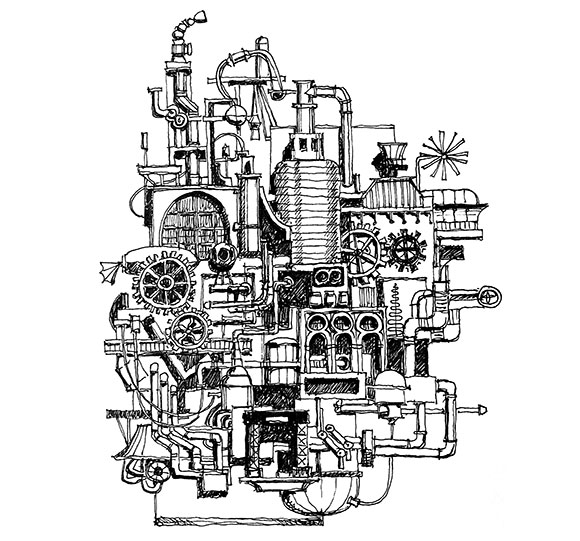

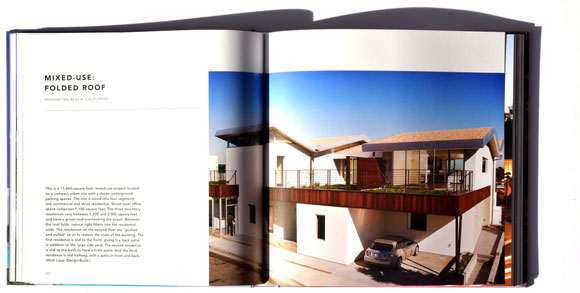

Anthony: Architecture is very methodical. It takes a long time to produce a building. There are a lot of practical considerations: code, budget, square footage. You can’t just whip out a building the way a jazz musician would whip out music. But in the creative process, I always wonder: Why can’t we just grab colors and make an idea? Why can’t we have this sort of jazz-like conversation bouncing ideas and simply grab at this and that, and make it the basis of an entire building design, whether it’s a library, museum, or house?

Brian: Let’s go back to this question of architecture and narrative. Could you talk about the importance of storytelling in design?

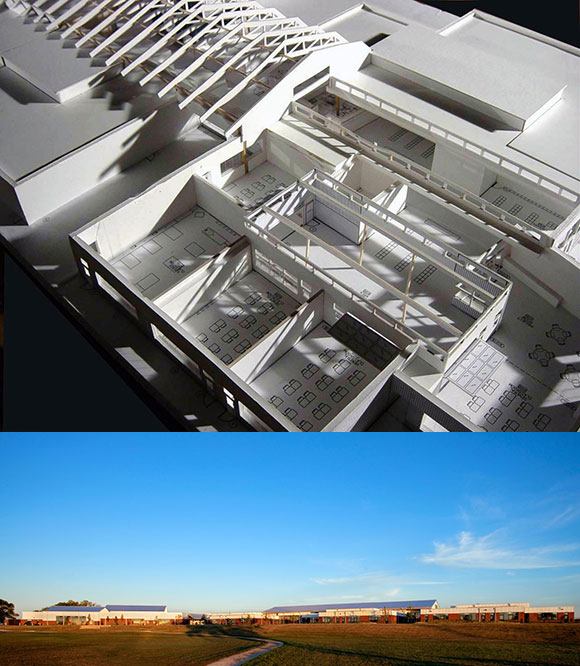

Anthony: It’s all about communication. Everything that I do––painting, music, writing, architecture––is all a language. In architecture, we look to our clients—who they are and what they are—to craft a story. If it’s a family, we want to know how they celebrate the holidays, if the in-laws stay with them, whether they have dogs. For designing a school, we ask: How do the teachers teach, how do the students learn? With an office: what’s the corporate culture, what’s the mission statement? When we do a religious project, there is an entire set of beliefs that need to be expressed in architecture. What’s exciting about music and architecture, and what makes them different from writing, is that they are abstract. It’s kind of open-ended communication.

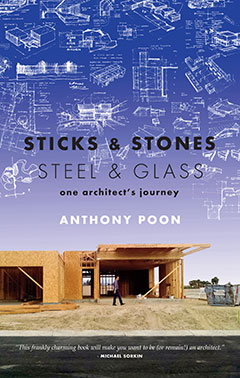

Brian: In your memoir, Sticks & Stones | Steel & Glass: One Architect’s Journey, you write about designing intimate spaces for people.

Anthony: What we talk about at my firm is that good design belongs to everyone. It could be a restaurant or the design of a bench—corporate headquarters or a public school. It’s about harnessing the talents that my team brings, and then reaching as many people as possible.

Brian: Where do you stand on the introvert-extrovert scale? Because architecture, especially when you get to a certain scale, is teamwork. Painting, which you’re also acclaimed for, is a more solitary activity.

Anthony: I’m probably somewhere in the middle but skewing a little towards the extrovert side. Some of these art forms are solo explorations, but I don’t see the art being complete until it reaches the audience. That’s the completion of the artistic arc. With any kind of artist, both introversion and extroversion are tapped. In architecture, for example, the introverted, introspective, self-examining qualities usually launch the design process, and the extroverted side leads a team, sells the idea to a client, and supports the creative ego.

Brian: In Sticks & Stones | Steel & Glass, you described how San Francisco’s Portsmouth Square in Chinatown inspired you. The park dates to 1833, but its 1963 redesign was derided at the time for raising the park to fit a parking garage underneath. What made it special to you and the community?

Anthony: Isn’t it incredible that it is a parking structure and an extraordinary park? The plaza acts like a blank canvas, and the community paints their life onto this canvas. It’s just that kind of wonderful, idyllic place that you don’t imagine would be in such a dense area. I look at Portsmouth Square, not as an architect fetishizing its design, but as what it offers to the community: to have a Tai Chi class at 5:00 in the morning, a wedding at noon, and kids running around in all day. That’s the power of architecture.

A manifesto is quite ambitious. I could also be accused of being naïve to think that I could write a manifesto, whether it’s a paragraph or 100 pages. I think I prefer the

A manifesto is quite ambitious. I could also be accused of being naïve to think that I could write a manifesto, whether it’s a paragraph or 100 pages. I think I prefer the