#130: TO DRAW OR NOT TO DRAW—THAT IS THE QUESTION

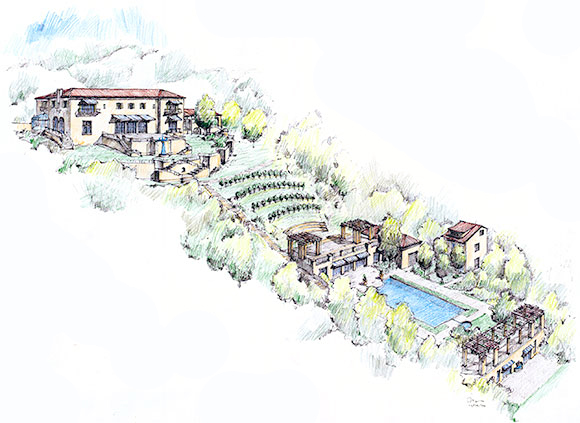

Hand sketch with colored pencils of Villa Sunset, Beverly Hills, California, by Martin / Poon Architects (drawing by Anthony Poon)

To capture the spirit of a proposed architectural design, the human hand once held a pencil. For better or for worse, that same hand uses a computer these days.

Long before the advent of technology, architects drew by hand—ink on paper, for example. Sometimes meticulous and detailed, other times expressive and abstract—handmade presentations communicated the design vision for a client.

Drawing was an intuitive process, where a few loose but curated lines could imply the Big Idea. The illustration was not burdened with capturing every last detail. The act of drawing, where the felt tip of a marker tracked along a softly textured surface of vellum, that in itself was an event of artistry and physicality. Yes, an art form.

Come the 60s and 70s, and IBM Drafting System introduced something that forever changed how architects designed and communicated ideas. The Brave New World was Computer-Aided Design and Drafting. The acronym CADD, or simply CAD in recent years, promised a technological future. These days, CADD or CAD sounds as archaic as labeling something “space age” or “high tech.”

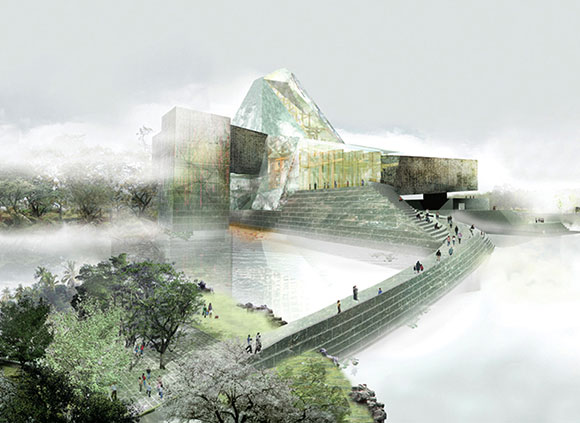

Nonetheless, it wasn’t long after the design industry embraced digital technology that rendering software would allow architects to represent their two-dimensional drawings as images suggesting the real thing—as if the project was built and someone took a photograph.

But the early versions challenged clients (here and here). With the pretense of a presentation image looking sort of like physical reality, the clients stared too closely at the computer-produced rendering. High gloss images were produced to convincingly sell the design idea. Architects expected clients to be thrilled by the fetishized images washed in idealized sun and reflections, over saturated with colors and faux material. Unfortunately, circular conversations went like this.

Architect: “Here is what your building will look like!” A computer rendering is proudly presented.

Client: “Wow, it looks so real already. What kind of stone is that? I don’t like marble with so much veining. How come the joints are so big? What is the finish on that light fixture? Bronze?” The client starts to get confused.

Architect: “Oh, sorry.” Back peddling quickly, “This is just a mere preliminary concept. Umm, we used the computer to apply textures, shadows and materials, but the software is limited. It probably won’t look like this at all. Oh, yeah, so if you are worried, don’t be. This is just a computer drawing.” Sounding weakly apologetic.

Client: “Then why did you show it to me, if it isn’t going to look like this?”

The next iterative step for computer renderings tripped dangerously into video animations, also known as “fly throughs.” The shortcomings of the early computer renderings were many times worse when trying to provide a short quasi-realistic film for the client—a feeble video tour that was so to present what it might feel like to walk into the proposed new house, viewing room to room. Things did get better though.

These days, the technology behind Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality are delivering architect and clients into exciting, but still to-be-tested, waters. Promising yes, but lots of hiccups to come.

The challenge is this. When the architect and his software represents the design as a realistic photograph, video, or AR/VR, it will inevitably fall short of reality. The answer, whether drawing by hand or using a computer, is to not just capture a physical reality at a sample point in time, but rather, capture the emotion. Instead of trying to show the exact brick pattern in the picture, embody the atmosphere, character, and personality instead.