(DI)STRESSED OUT: LIFE WITH PATINA

My fave pair of jeans, by AG (photo by Anthony Poon)

What is it about our favorite pair of jeans—weathered and perfectly broken in? How about the ol’ leather jacket—worn and faded? The lustrous surface, cracking a little—almost poetically.

But a car. No one wants a car that has been distressed, with a shattered windshield and scratches on the sides. No, we want our cars immaculate. Like new.

Many think of architecture like a polished car. Buildings should look new. Buildings are constantly being renovated, and historic buildings restored to their original sheen.

But why not we embrace a building as worn, like our denim jeans or favorite leather shoes?

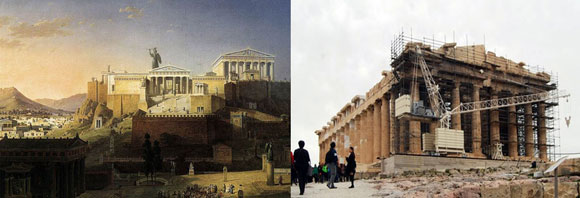

Consider the dreamy paintings of Antiquity, with the gleaming majesty of white temples. Think of how they look today: tired, old, covered in both soot and scaffolding. Most buildings can’t look the same as they did on the first day.

And I argue that they shouldn’t.

Amazon summarizes the book by my thesis advisor, Mohsen Mostafavi, On Weathering: The Life of Buildings in Time. “On Weathering illustrates the complex nature of the architectural project by taking into account its temporality . . . weathering makes the “final” state of the construction necessarily indefinite, challenges the conventional notion of a building’s completeness.”

I suggest that we embrace building materials that patina with inherent beauty. I think of the tag that comes with my jeans, “Variations and changes in color and surface are not defects of the material, but considered to be part of the fabric’s natural beauty.”

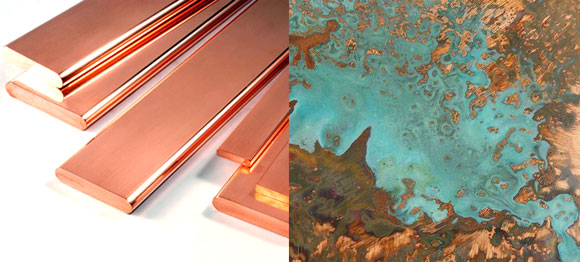

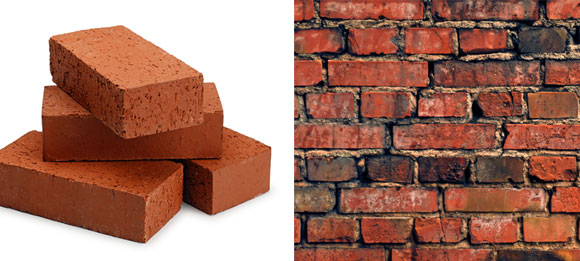

Copper, for example, expresses evolution and maturity, as it starts shiny and bright, deepening to a rich “dirty penny” brown, eventually becoming a vivid and brilliant green. Bricks begin life as a crisply cast block of masonry. Over time, the edges soften and the surfaces crack a little. The standard red color becomes twenty different shades of the hue of origin. Consider the 200-year old brick sidewalks of Boston.

Materials aside, allowing architecture to breathe, express its age and soul, and change even mutate—all this displays character and life, like the worn grooves in a wood service stair. Progress: A caterpillar does not exist only as a worm.