JAZZ-LIKE: THE CURIOUS THING ABOUT STYLE, PART 2 OF 2

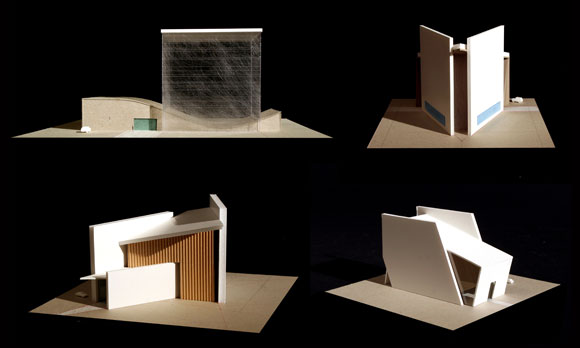

Kit-O-Parts concept model for Chaya Downtown, Los Angeles, by Poon Design

What can architecture learn from jazz? Specifically, what can architects designing buildings learn from musicians creating jazz?

I recently posted my design approach as two parts: Product and Process. In that post, I discussed the ‘Product’ being works of juxtaposition. In today’s post, I explore my ‘Process’ being jazz-like.

Many things bog an architect down, such as calculations that ensure a structure won’t collapse. Budgets, city codes, and construction surprises also burden us. The nature of our day to day design work is slow and tedious. From start to finish, a completed building requires years or decades. Even generations. Whether Rome’s St. Peter’s Basilica or a local wine store, the architectural process is sluggish and overwrought. At times, painfully so.

With graphic design, on the other hand, a logo can be designed and implemented efficiently. In less than a month, boom, the logo appears on a website. (Sorry, my graphic artists’ friends, I know it is much more complicated than this, but in comparison . . .)

In jazz, musicians sit at their instruments, glance at each other, perhaps a wink, then a smile. And boom: music. A jam session begins, and the audience immediately enjoys the sounds and rhythms.

Spontaneity and improvisation are words that describe jazz. In contrast, as a classically-trained pianist, I was taught a mindset akin to architecture, where at great lengths and with agony, each and every move is carefully conditioned and rigorously rational.

When performing Liszt, I wouldn’t just discard the sheet music and riff on an Etude. Or maybe I would, but then it becomes something other than Liszt—and that might not be good. With architecture, I wouldn’t just discard the structural calculations for a hillside foundation and doodle my own geotechnical assumptions. A well-built castle isn’t constructed on sand.

Is there room for speed in architecture? How about intuition? Social psychologist David Sudnow comments on jazz as moving “. . . from no one place in particular to no one place in particular . . .” I wish architecture had this kind of freedom.

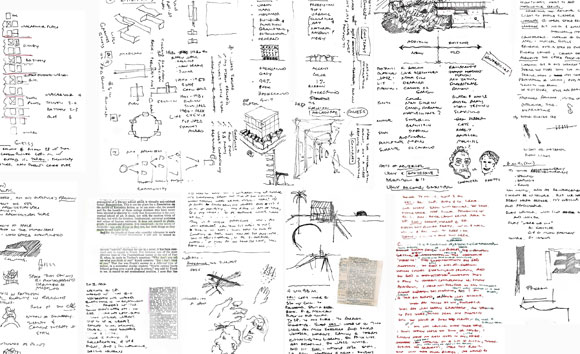

Though I can’t actually be like a jazz pianist playing impromptu, I still try. Every day, I attempt to hand draw ideas freely without the constraints of either a T-square or the laptop. Rather than picking the appropriate shade of olive from the Pantone color book, I use my color markers and pencils. Swiftly and even blindly, I grab at colors, blending in a mad flurry seeking hues of discovery and spontaneity.

Jazz and juxtaposition—two words I might use to describe my work. Very likely, I will replace these two words with different words the next time an interviewer asks me, “What is your style?” In the end, I leave the labeling of the work to the historians, intellectuals, critics, and fans. When I am long gone, I hope my design legacy is given a provocative designation of style.

(For more, see a feature on my process at The Art Issue of LA Home magazine.)