#142: NEW MEETS OLD: INTENTIONAL ACTS OF DISRUPTION

Royal Ontario Musuem, Toronto, Canada, by Studio Libeskind (photo from libeskind.com)

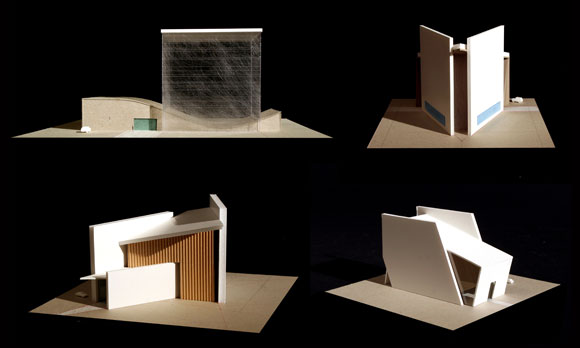

When adding to an existing building, the conventional agenda requests that the new structure match the old. A typical client request suggests that the point of connection between new and old be “seamless.” But there exists a different school of thought, a provocative one. Here, the new structure not only contrasts the old, but the addition is intentionally disruptive.

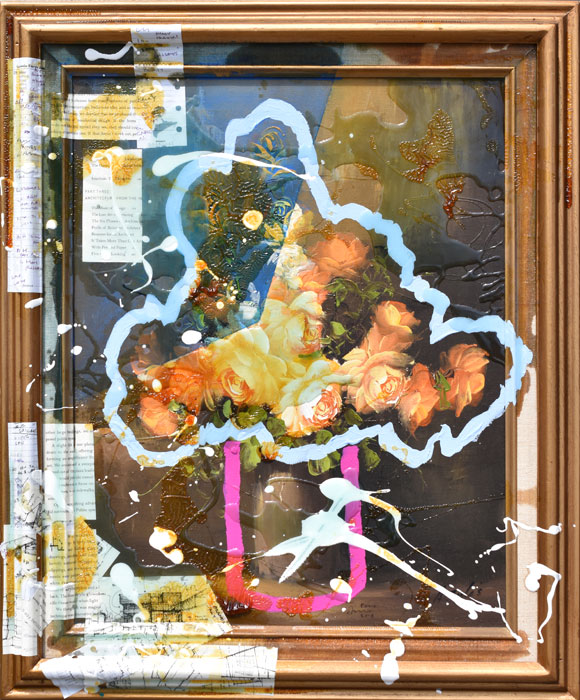

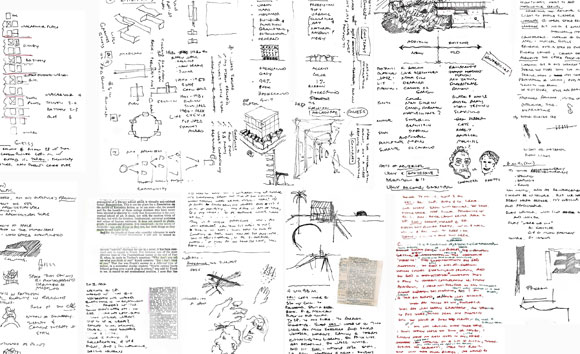

Whether a new hotel wing, library expansion, or guest bathroom, adding onto an existing building results in a form of symbiosis. As described in science, a symbiotic relationship is two dissimilar organisms in close physical association. Architecture may not always be thought of as a living thing. But the way a space breathes with light and air, or when a building comes alive with visitors and experiences, or how a structure houses memories and enlightens the human spirit, architecture is indeed a unique form of organism.

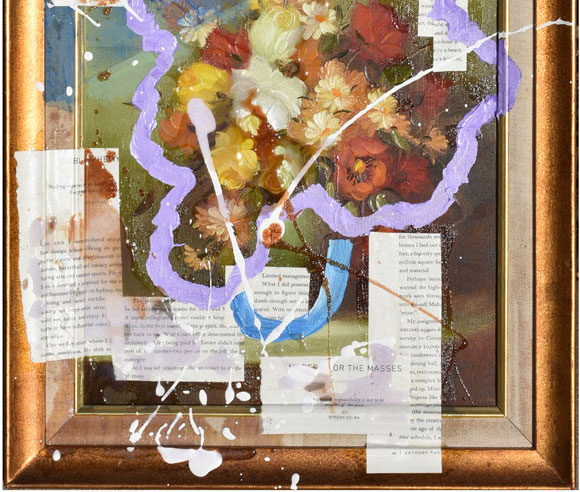

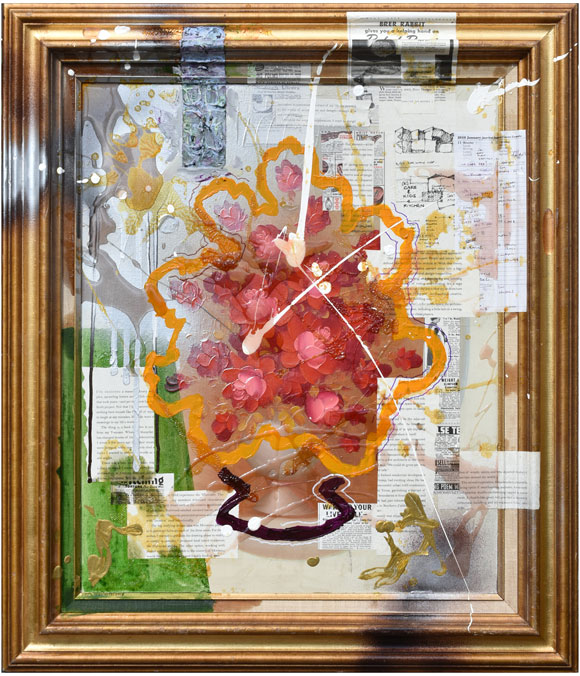

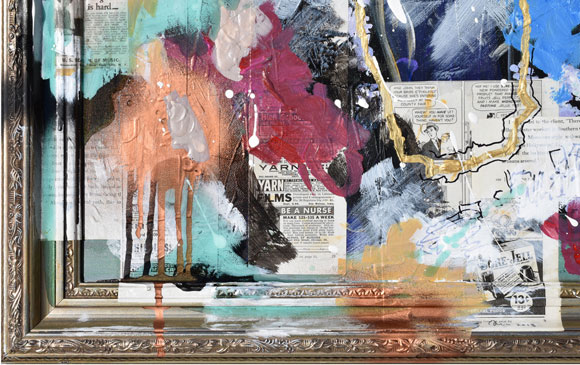

When new meets old, the design can be traditional, even predictable, as in the “seamless” approach, where a visitor can’t tell that a building addition has been delivered. But the design can also be divisive, where the addition exploits the host through a parasitic relationship. With the old building as host, a new structure is an intervention, at times predatorial. This approach creates tension, a vibration between new and old, and results in a fantastical world of the unknown. We don’t just see the two parts, the new and the old. Now, we view a third thing: the relationship between new and old. One plus one doesn’t have to equal two.

In these examples, there exist no seamless transition, no resolution, no settled serenity. The designs are intentionally disturbing and anxious, perhaps a violent act of the architect. Like the grandstanding of creative ego, the hand of such an architect is akin to a street artist tagging a building. Some call it vandalism, and some call it art.

Perhaps it is true that “opposite attracts,” as stated by psychologist Robert Francis Winch in the 50s. Or in this case, having architectural opposites can be deemed attractive. The projects seen here are not necessary outliers. The trend of confronting one’s context in an unexpected way has been around, ever since architects looked at their neighborhoods and believed there should be something new to do, something else. Like the urge to play hard rock music in a tranquil and pristine chapel.

It’s the desire for contrast. From Google: contrast, noun, /ˈkänˌtrast/: the state of being strikingly different from something else in juxtaposition or close association.

Nearly everyone wants to be noticed in one form or another—even introverts. For some, to conform with the faceless masses and banal circumstances is to give up on the ambition to be an individual. We want to be distinctive. And noticed.