#207: THE BRUTALIST | FILM REVIEW BY AN ARCHITECT

Library renovation, Laszlo Toth’s first project for his new client, Harrison Lee Van Buren, film still from The Brutalist, 2024

Over time, architects have appeared in hundreds of movies and TV shows—from Paul Newman to Tom Hanks, Michelle Pfeiffer to Sharon Stone, Keanu Reeves to Elliot Page. But this architect trope is rarely integral to the story. With the 2024 film, The Brutalist, we finally have a movie with an architect being an architect. But I raise an eyebrow or two.

Sure this Oscar-winning movie—3 hours and 34 minutes—is grand and ambitious, an epic sweep of heroism and faltering humanity, like many Oscar films. All blubber aside, I question the accuracy of the architect’s portrayal, the fictional Laszlo Toth—loosely based on the famed architect of the Brutalist movement, Marcel Breuer.

Please know this: My movie review is not so much a critique of narrative structure, directorial agenda, and cinematic achievement. Rather, as an architect, it is the details about architecture that vex me.

First, the design proclamations are pretentious, even ridiculous, but perhaps it is accurate for the many architects who fall victim to what is mocked as “archi-speak.” Example from a Harvard architect, “Unlike architecture that seeks to articulate understandings about the nature of things through expressive or metaphoric mimings, this remarkable building yields us actionable space.”

Our hero, Laszlo Toth, spews lines like, “Nothing is of its own explanation. Is there a better description of a cube than that of its construction?”

And “…skylights that can also be viewed as demarcations of units of space…”

Or “For its harmony.”

The chapter titles also encourage teasing.

– The Enigma of Arrival

– The Hard Core of Beauty

– The Presence of the Past

Of the script, Dezeen magazine critiqued, “Like the architecture itself, the conversation is cliched nonsense”

Next, an architect is usually not a general contractor nor a structural engineer. But in The Brutalist, Toth is actually determining the number of construction workers needed and providing construction techniques. Every attorney to an architect will scold said architect for providing liability-stricken “means and methods” for construction. Architects design. The contractor builds. Simple as that.

Speaking of the architecture, apparently no architects were consulted for this film. Perhaps one should have been hired to collaborate with the production designer, Judy Becker—competent and compelling, but appearing to have limited formal architectural training. For a movie about boxing, shouldn’t a boxer be consulted? For a movie about cooking, shouldn’t a chef be consulted.

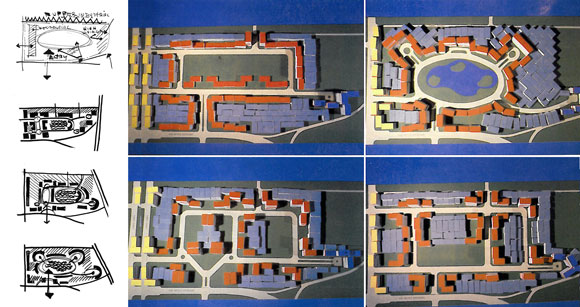

We see familiar references to the work of Louis Kahn, Mies van der Rohe, and Paul Rudolph, but the resulting architecture, particularly the “visionary” community center—Toth’s career breakthrough project—is mildly interesting at its best, clunky at its worst. For that scene of the big presentation, I doubt any architect would walk into a public hearing with such a clumsy-scaled, crudely-made, white cardboard model.

Lastly, if the actor, Adrien Brody, is going to use architect’s drafting tools, he should use them correctly, holding them, drawing with them. It’s like watching a movie where the assassin holds his gun upside down. And I don’t know many colleagues that draw with fat sticks of black charcoal. Artistic-looking on screen, yes, but practical?

I did sympathize with the sensitive, customer-serving architect who gets abused by the self-serving, affluent client—in this case (spoiler alert), literal rape.

I liked and disliked The Brutalist. Though I found fault in the portrayal of Laszlo Toth as an architect, I supported much of his depiction: thoughtful, creative, and bold, but also self-absorbed, uncompromising, and egotistical. Best to sum it up as Fountainhead-syndrome.