#128: BLURRING THE BOUNDARY BETWEEN ART, SCULPTURE, AND ARCHITECTURE

(photo by Hunter Kerhart)

Architecture can—and most definitely should—be artistic. Masterpieces such as both Guggenheim museums, in New York City and Bilbao, Spain, are called “works of art” by pretty much everyone. Interesting that a legendary work of art such as the Monet’s Water Lilies would never be referred to as an exquisite “work of architecture.” Some sculptures on the other hand, such as those by Richard Serra, are indeed called architectural.

Poon Design was honored to be commissioned by two global hospitality brands, the Ritz-Carlton and JW Marriott at the 27-acre L.A. Live in downtown Los Angeles. The Ritz stands proud as one of the highest standards of quality, earning the colloquial adjective that defines sophistication and elegance, “Ritzy.”

At the existing porte cochere and main entrance to the 54-level luxury hotel and residential high-rise, our client challenged us to replace the hundred foot long fence with something innovative. Not only was the existing fence not at all Ritzy, it was more akin to a low end motel—the fence barely better than a commercial chain link screen. Failing dramatically, the 9-foot tall fence was supposed to accomplished several things, most importantly: provide security and privacy to the residents and visitors who comprise high net worth individuals, Hollywood stars, celebrated athletes, and the like.

Alongside creating a unique privacy scrim, the Ritz-Carlton gave Poon Design additional design objectives:

– Present a notable front door for a world-renowned brand,

– Provide security to the residents and their luxury cars arriving at the porte cochere,

– While providing privacy, allow natural light to enter the porte cochere, meaning, not a solid fortress-like wall,

– Screen out the movie complex across the street which brought glaring lights, noisy customers, and trash, and finally,

– Establish a friendly face, but one that can protect the hotel from bystanders, loiterers, and paparazzi—again, but not a fortress-like wall.

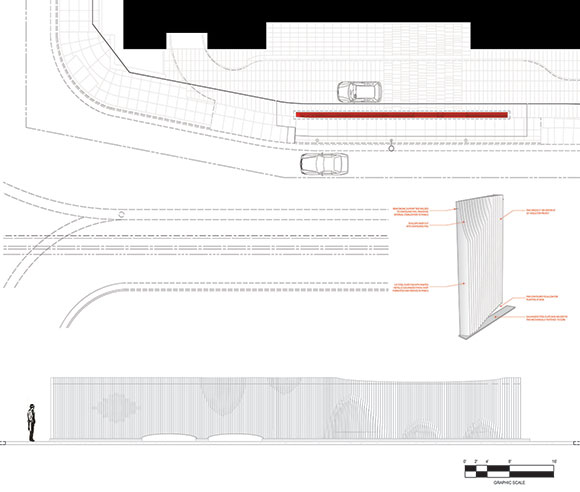

The assignment was a triple-threat challenge of architecture, sculpture, and art. In response, we designed an 87-foot-long statement of contour and texture. Our 260 shaped steel fins at 10’-6” tall guard the Ritz-Carlton, while projecting a distinguished curbside appeal and allowing in dappled sunlight.

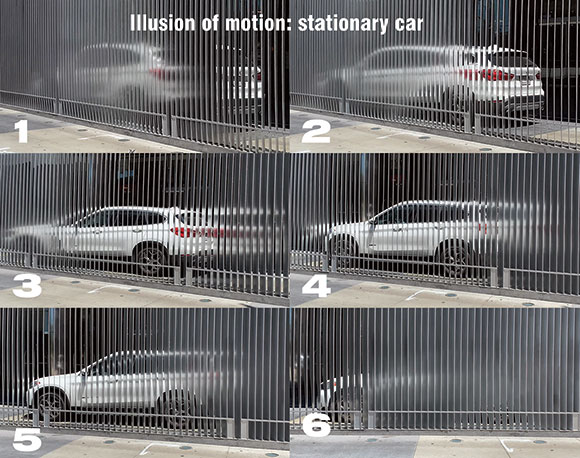

As a visitor moves alongside this wall of ever-changing angled slats, her views, perception and exposure to light constantly and mysteriously change. Even a stationary car on the other side of our wall appears to be in motion.

In addition to the uplights in the ground, the steel’s powder-coated silver surface captures the constantly changing colors of the theater’s flashing signs and lights from across the street, and reflects it back as an everchanging light show.

Is it architecture because it is a mere freestanding wall—an element of a building? Is it sculpture that happens to serve many programmatic functions from security to trade dress? Or is it art because it’s sublime presence surpasses the base purpose of being just a piece of architecture?