#141: SEATTLE HEROES AND ICONS

left to right: Seattle Century Library; Museum of Pop Culture; The Spheres, Amazon (photos by Anthony Poon)

Upon a visit to Seattle, I confronted three different buildings—all leaving a seductive imprint on the city and my memory.

– Seattle Central Library by Pritzker-laureate Rem Koolhaas,

– Musuem of Pop Culture by Pritzker-laureate Frank Gehry, and

– The Spheres at Amazon by corporate NBBJ.

The first two projects are by two of the most famous living architects on the planet. The third is by an anonymous company, one without the trappings of a sole Wright-ian genius which gives way to collaboration instead—for better or worse.

(Three disclaimers: Rem Koolhaas was my professor in grad school; I was employed by NBBJ in the 90s; and I did not have an opportunity to visit the interiors of The Spheres.)

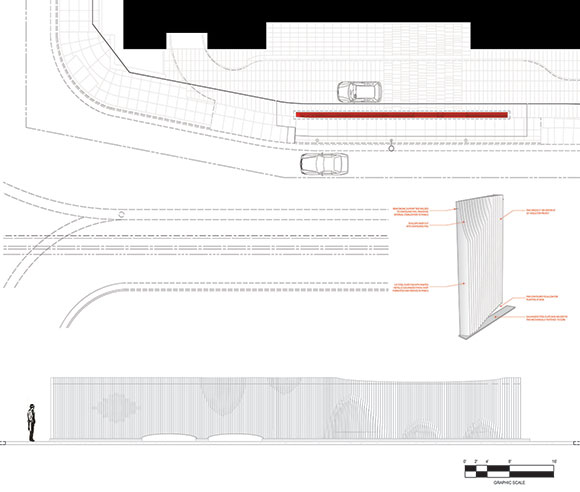

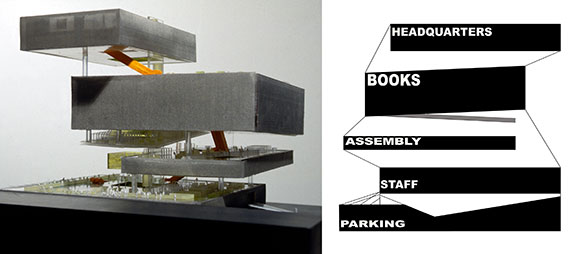

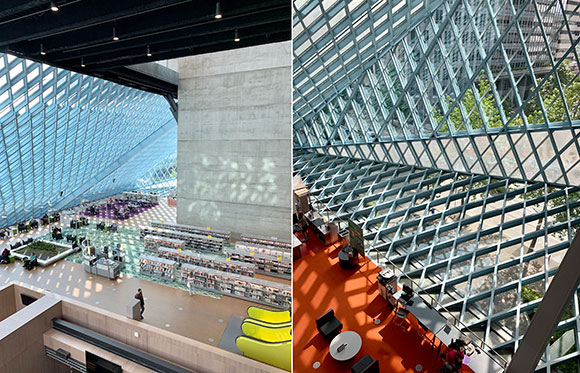

THE SEATTLE CENTRAL LIBRARY

The Seattle Central Library, designed by the Rem Koolhaas and shepherded by local Architect-of-Record, LMN, opened to the public in 2004—the winner of a lengthy design competition. The reviews of this 11-level, 363,000-square-foot building varied.

The international architectural scene claimed the design a heroic success. Others saw a design with a target on its back—and its front too. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer spewed adjectives: “decidedly unpleasant,” “relentlessly monotonous,” and “profoundly dreary.”

I side with the glorious praise hailed from the enlightened world. The library design comprises community spaces that engage the public on many levels, (literally) as well as a civic icon unlike anything seen before.

As Professor Koolhaas taught us in school: Do not design simply in floor plan, meaning, not just one-dimensionally laying out an auditorium next to offices next to restrooms. Instead, design in section, meaning, three dimensionally as one places a library over a five-story high living room, then tucking parking under the auditorium.

The library’s innovative and challenging (yes!) urban form, the diamond-patterned skin of glass and steel, a four-level spiral of books, a complex layering of space and experience, and so on—all this together convinces me that I have walked into one of the most exciting works of contemporary architecture.

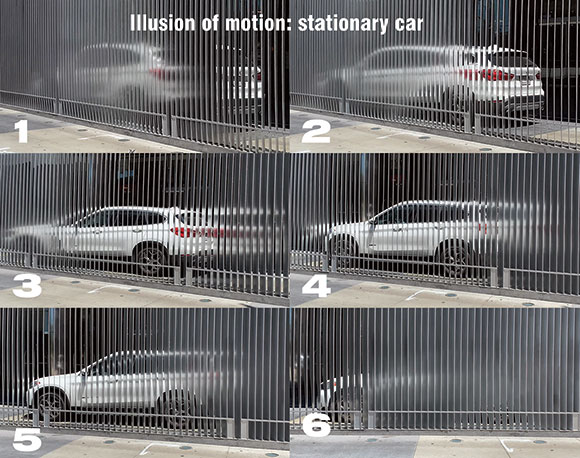

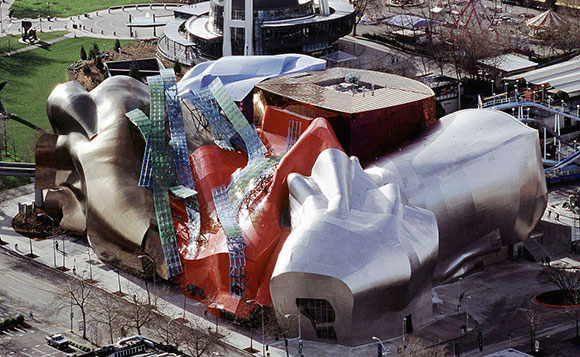

THE MUSEUM OF POP CULTURE

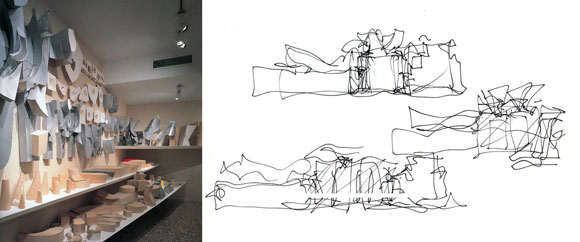

The Museum of Pop Culture, coined “MoPOP,” opened in 2000 under the former name, the Experience Music Project—coincidentally also included the participation of the same Architect-of-Record, LMN. Frank Gehry’s design, though predictable and yet another variation-on-a-theme (nearly a career-long theme) offers passerby’s a composition of great risk and resulting beauty.

According to the client, “When Frank O. Gehry began designing the museum, he was inspired to create a structure that evoked the rock ‘n’ roll experience. He purchased several electric guitars, sliced them into pieces, and used them as building blocks for an early model design.”

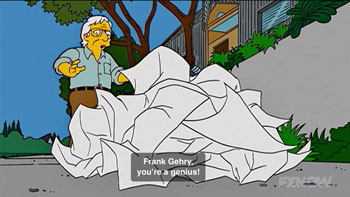

Such tales subscribe to the mad artist genius syndrome. True or not, it makes Gehry sound like less of a thoughtful architect creating wonderful spaces for the public, and more like an awkward child who believes that the broken pieces of a guitar can represent a work of architecture.

Five giant building masses sit at the base of the Space Needle, each mass clad in enigmatic surfaces, like fire-engine-red stainless steel or fuchsia-fluorocarbon-coated aluminum—comprising a total of 21,000 individually cut metal shingles. As an object, as architectural sculpture, the composition is stunning. Does not disappoint. Having the monorail pass through the building is yet another daring move that delivers a thrilling creation.

But the 140,000 square feet of interior space underwhelms, fails to translate the exterior exhilaration to the indoors. Whereas the Seattle Central library sings with its visionary interior design, MoPOP falls out of tune. Aside from a few flourishes, like a dynamic staircase or a contorted lobby space, most of the museum’s inside is not much more than generic exhibit space. One might argue that a museum’s interiors should be flexible and so inherently boring, but I would then direct your attention to the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, also by Gehry.

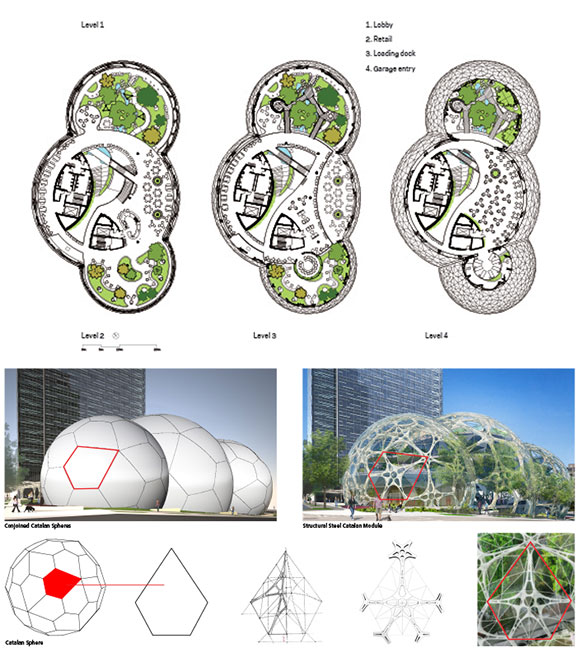

THE SPHERES, AMAZON

You don’t need the singular vision of great artistic minds like Koolhaas and Gehry to deliver good architecture. Unlike the first two projects, NBBJ played the role of Design Architect and local Architect-of-Record, meaning both the creative lead as well as the development and production team.

Aptly named The Spheres, Amazon’s new workplace and quasi-visitor center is made of three giant glass and steel spheres, colliding like a kid’s exhaled soapy water bubbles. Recently completed in 2018, Amazon claims, “The Spheres are a place where employees can think and work differently surrounded by plants.”

Is it just another glamorized office? Just more “creative office space” glorified by real estate agents? But the phrase “surrounded by plants” fascinates me.

The spherical structures, conservatories actually, house 40,000 plants from over 30 countries. Within a meticulously engineered structure of 2,600 pentagonal hexecontahedron panes of glass alongside 620 tons of steel, I see one of the finest examples of biophilia. For reference, a past article, “Biophilic Design refers to our instinctive association to nature and the resulting architecture that enhances our well-being.”

Aside from the obvious design reference to Buckminster Fuller’s utopian geodesic domes of the 60s, the Amazon Spheres offer a new narrative for office space, retail, café, and meeting places. NBBJ has shed the dogmatic aim of developers to maximize floor area. Similar to Koolhaas, NBBJ celebrates the magnificence of volume, as in cubic footage (or in this case, spherical footage) and the capture of air, light, and a more productive work culture.

The total result is impressive, likely to be a local fan favorite and on every city tour guide. The design is good, even great, but is it inspired? Will it change the world? Probably not.

But the Seattle Central Library has already influenced the way architecture students think, the way teachers teach, the way professional architects design. Most of Rem Koolhaas’ projects deliver new ideas beyond form-making, embracing social engagement and re-inventing the meaning of living, shopping, or learning.

Frank Gehry, on the other hand, seems to be playing the same note over and over again. But is that wrong, especially if this one note is sheer genius played with virtuosity?