#200: THE MYTH OF THE MULTI-HYPHENATE

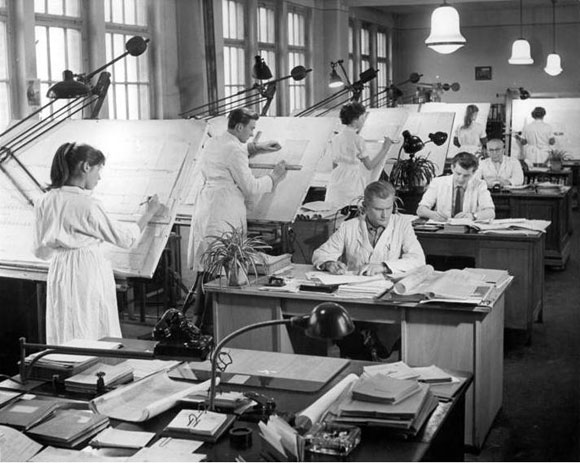

(photo by Anthony Poon)

For my 200th essay (I congratulate myself for this achievement), I look inward: What does it mean to be accomplished, if one ever is?

J. Lo (as in Jennifer Lopez) is often called a “triple threat” or a more popular label, the “multi-hyphenate”—as in singer-dancer-actress, as in singer hyphen dancer hyphen actress. But I question her multi-use of hyphens.

Yes, she is successful as a pop singer, a “threat” to her colleagues and competitors. But as a dancer, is she a threat to other dancers? Is J. Lo taking away ticket purchases from Alvin Ailey and Martha Graham. Or for acting, does Meryl Streep feel threatened by J. Lo because she might steal away Streep’s next Oscar? The point is that J. Lo is more of a single threat, and the hyphens aren’t authentic.

A colleague once published a tiny article for a magazine. From that point on, she called herself an “author,” though she never wrote another article, let alone any books. But her supportive friends graced her with the descriptor, “Renaissance Woman,” in reference to the Renaissance legends like da Vinci, who hyphens identify him accurately as an architect-artist-scientist-sculptor-mathematician-engineer-inventor, and so on.

My LinkedIn handle states, “Architect-Author-Musician-Artist.” I don’t consider myself a quadruple threat, but I do consider my hyphens earned.

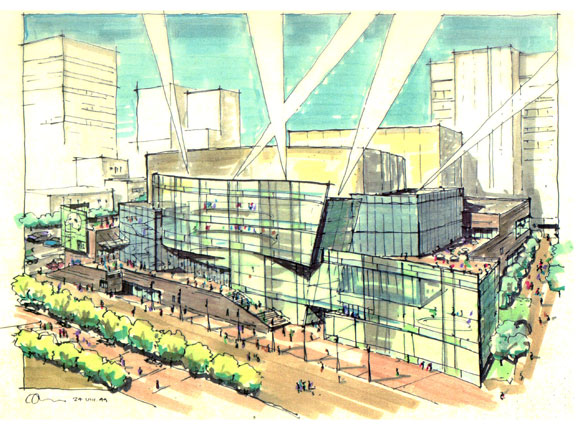

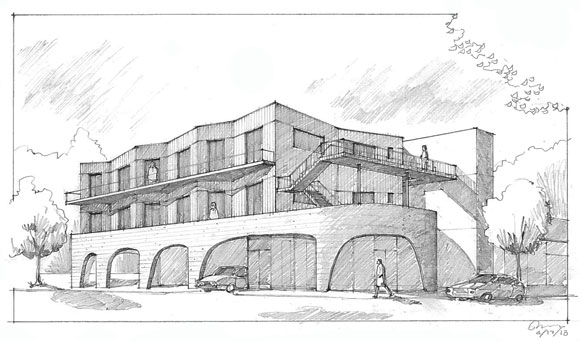

I aim to be an above-average architect. I have won many national awards and have been written about in hundreds of articles. I have the distinct honor of being deemed FAIA, the highest membership honor in the AIA, for “exceptional contributions to architecture and society nationally . . . awarded to the top 3% of the country’s industry.” I believe I am an above-average architect, but I don’t have the Pritzker.

I aim to be an above-average writer. I have published three books (here, here and here), with a fourth in the works. I have written over 200 industry articles. And I even wrote a screenplay about architects being murdered as they compete for a career-making project. I believe I am an above-average writer, but I don’t have the Pulitzer.

I aim to be an above-average musician. I have trained in all the classics, from Bach to Beethoven to Brahms. I have performed in regional recitals and engaged piano competitions, winning a few. I have taught my two daughters piano, and I have even attempted to learn Thelonious Monk’s, Round Midnight—a challenge for a classical pianist, like asking a ballerina to dance hip hop or an opera singer to rap. I believe I am an above-average musician, but I don’t have a Grammy.

I aim to be an above-average artist. I paint all the time. My work has been exhibited from California to Cambridge, from cafes to galleries. I have sold a number of my works, and recently won a prized ribbon at the annual Beverly Hills Arts Show for my mixed-media paintings. Drawing was my first creative endeavor as a child, placing a large piece of plywood on the carpet and using it as a makeshift drafting board. I believe I am an above-average artist, but I am not exhibited in the Louvre.

What does it mean try to be above-average, to be accomplished? Perhaps if I didn’t fiddle so much, I could focus on one field and excel from above-average to truly great. But as I consider limiting my creative pursuits, I only think of more. What’s next? Car design? Writing a musical? Being a chef? Knitting?

I view all my explorations as one, that there is little difference between each of them. Joy comes whether I am designing a university building or writing a novel, learning a Mozart sonata or painting a portrait. It is all a singular force of needing to make something, tell a story, and leave behind something worthwhile. This might mean the common link is that all my exercises appear to involve an audience—one attendee, dozens or thousand—a visitor to a temple I designed, a reader of my essays, a listener of my music compositions, or an observer of one of my paintings.

We all have ambitions, and more often than not, we don’t reach them. Maybe it comes down to finding happiness.

And happiness is based on defining what makes you happy. How have you crafted your life? Where have you chosen to live? What is your work? Who is your partner? Who are your colleagues? What interests you? Is being accomplished the goal?

Add to this how reality TV (

Add to this how reality TV (