THE PERFECTION OF IMPERFECTION IN ARCHITECTURE AND MUSIC

Patina’d signage of Vosges Haut-Chocolat, Beverly Hills, California, by Poon Design (photo by Poon Design)

Wabi-sabi: This Japanese aesthetic concept has been around for centuries. Today, in our worrisome world, Wabi-sabi has returned with a vengeance and popularity. This philosophy describes a type of beauty that is imperfect, ever changing, and even, wonderfully flawed.

Intensely and vividly sculpted, Auguste Rodin’s sculptures displayed a desire to express an incomplete craft. Rather than the predictably perfect, classical marble sculpture, this 19th century French artist’s works are imperfect sculptures from the human hand. And he is eager to display his flawed humanity.

In Rodin’s finished pieces, one can see the imprints of his tools and fingers—and even his fingernails.

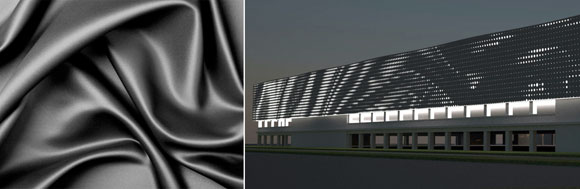

At Poon Design Inc., certain projects request that we celebrate what might be wrongly judged as flaws and inconsistencies in our architecture. We prefer hand-crafted architecture, not things machine-made or mass-produced. Like jazz, like weathering, like life with patina, our architecture expresses the perfection of imperfection. Or even the imperfection of perfection.

If technology in design and fabrication produces items that are too perfect, then technology can be a crutch. Although technology has made our production efforts efficient, technology has also made our activities too textbook-finished. Today, we can design any kind of wall pattern on a laptop, and then have water jet or laser cutting machinery create that exact pattern on several large slabs of marble or steel panels. With a push of a button, the quality is flawless, the exercise is easy, and the pattern is perfect. But perhaps too perfect.

If too perfect, is such a work impressive? Where is the human hand?

The graphic weight of a classical music score suggests a complete work, while the jazz score wants more notes. A jazz score is beautifully incomplete and imperfect. No matter how many musicians fill in the missing notes, the music may never be perfect. And folks, this is okay.

When I practice my classical repertory, it is at times painful and laborious—as I try so hard to hit each of the 500,000 notes perfectly. I strive for perfection, truth and the absolute.

In jazz, I am given only a basic outline. A jazz player fixates little on classical perfection. Jazz is intuitive and improvisational. As I stated that life with patina is good, jazz music encourages patina, imperfections and powerful individuality.

In classical music, when a wrong note is played, it is quickly buried under a flurry of other notes. When a mistake is made in a jazz performance, that ‘mistake’ is exploited as a wonderful and positive thing. The jazz musician will bang on that wrong note a few more times to make sure the audience hears it. The performer makes something new and special out of the wrong note. Wabi-sabi.