#164: THE PURPOSE TO REPURPOSE

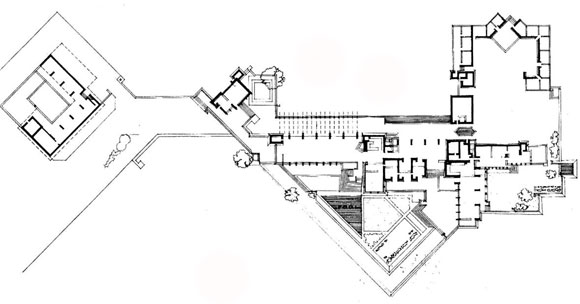

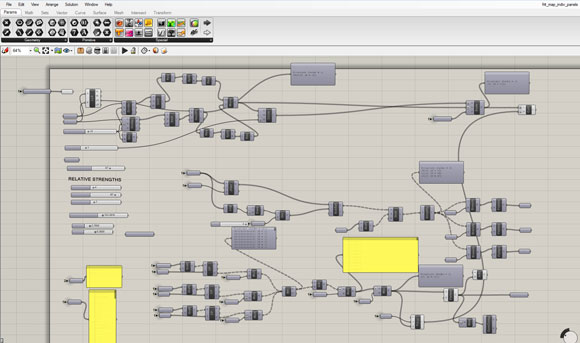

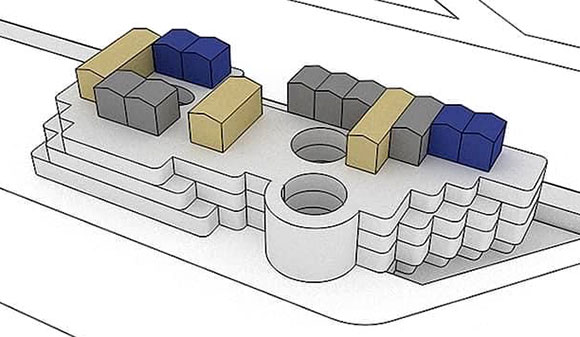

Proposed office-to-residential conversion, Beverly Hills, California, by Poon Design

Some have called it renovation or maybe remodel. Everyday lexicon might use recycle. Architects strive for adaptive reuse. And the most current language enjoys re-purpose. Whatever is your R-word of choice, the world of design has become less fascinated with the new and more committed to the re-new or renewal.

The New York Times recently wrote, “First, on a planet with limited resources and a rapidly warming climate, it’s crazy to throw stuff away; second, products should be designed with reuse in mind.” Calling out architects, “Buildings are responsible for nearly 40 percent of the world’s carbon emissions.”

Poon Design has been rethinking an existing 104,000-square-foot office building in Beverly Hills. Due to the pandemic, remote work, and changes in corporate culture, office buildings all over town are only partially occupied or worse, entirely vacant—empty carcasses of once thriving corporate activity. Accompanying this downturn is the demand for housing—apartments, condos, affordable/attainable housing, and/or workforce inventory. The Los Angeles Times summed it up, “Since the pandemic, the significant drop in employees showing up to work at an office has signaled building owners to consider converting office space into residential units.”

Our vision for repurposing this four-story office building into apartments involves renovating the existing structure and infrastructure, inserting more elevators and stairs, creating balconies and garden areas, adding a rooftop village of residences, and offering community functions, e.g. gym, café, meeting rooms, and social areas. And the building already comes with hundreds of underground parking. And repurposing doesn’t have to apply to entire buildings. Here are examples from architecture to furniture, toys to art.

At our design for Chaya Downtown, we collaborated with London-based artist Stuart Haygarth to repurpose 1,500 toys and collectibles into this feature chandelier. Countless toys are discarded by families each year. Thousands are lost at the beach or park. Many end up in the trash. Why not resurrect all these lost colorful playthings?

For this same project, we obtained handwoven baskets from Ten Thousand Villages, a global, maker-to-market, fair-trade retailer of artisanal crafts. We transformed these African baskets into garden lights. One might wonder how such a basket of fibrous tree and plant material can withstand the heat of an exterior light fixture. Our solution was clever: The light source is in the planting below the basket, not inside. Light shines up, the red and yellow colors of the basket transform the light into a warm glow, and reflect the beam downward.

Back to toys, I found myself looking at six dozen discarded stuff animals from my grown two daughters and a niece. Using an Ikea lounge chair as a frame, I hand stitched each animal to create this very comfortable and nostalgic piece of furniture. Sitting in it recalls one’s youth as she laid in bed surrounded by her favorite stuffed animals.

At Deluca’s Italian Deli, our millworker repurposed old wine crates and gave a curated personality to the community table, where Poon Design also custom designed all the furniture.

Ai Weiwei, the Chinese contemporary artist and activist, has explored several avenues of renewal and transformation in his large art installations. In London and more recently in Los Angeles, the artist led the production of 100 million “sunflower seeds” (hand-crafted in porcelain by 1,600 workers over two and a half years), and meticulously laid them out over the museum floor. The work asserts that the people of China can stand up together to counter communism.

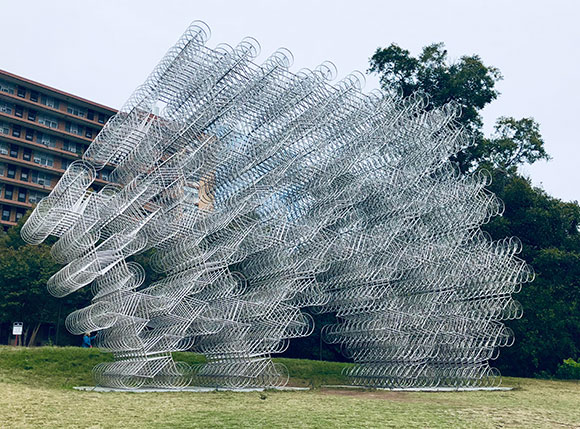

Weiwei’s gathering of a thousand ancient stools highlights the handcrafted nature of the three-legged seat passed down through generations, while simultaneously demanding attention from a world where such artisanal work has been discarded and replaced by the government’s latest identity, one of mass produced plastic and metal.

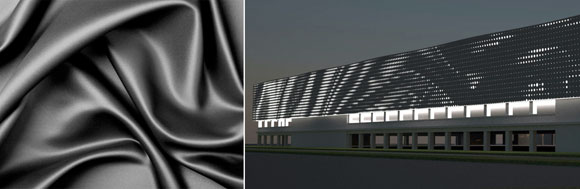

Similarly, this artist yearns for the authenticity of Chinese peasantry and their bicycles, the method of transportation most used by that class. Once expressing movement, the bikes now are combined together as sculpture, representing the current lack of freedom and the fixed society of contemporary China.

Through my mixed-media art, I too have explored the telling and re-telling of narratives, where I repurpose discarded old paintings, having a conversation with an artist I have never met.

Resurrection has its many Christian connotations. The Latin root, surgere, references a resurgence or revival–literally “to rise.” Whether a building or basket, stool or stuffed animal—whether repurpose or adaptive reuse—Merriam-Webster states that resurrection is “an instance of coming back into use or importance.” Again, why do we “throw stuff away”—from household items to entire buildings?