#180: PRACTICE MAKES PERFECT

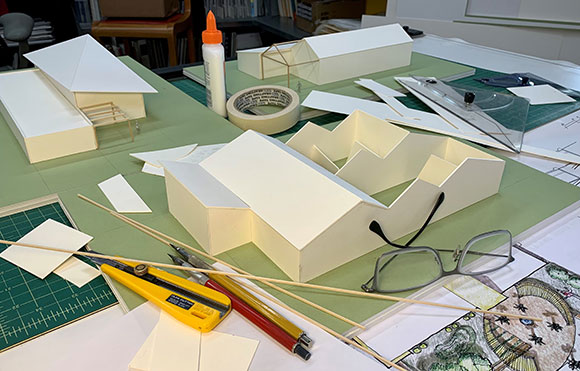

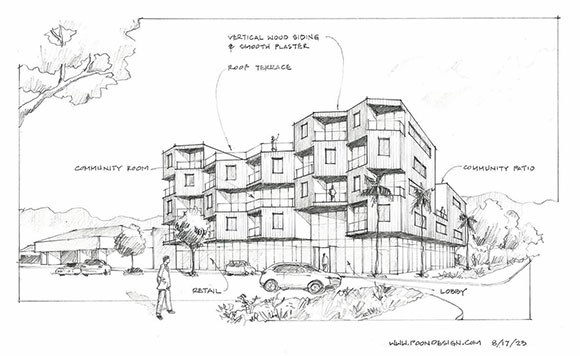

Study models, Golf Performance Center, Los Angeles, California (photo by Anthony Poon)

We architects call our industry the “practice of architecture.” This is so, because we are still practicing. It is not called the accomplishments of architecture or the perfection of architecture. It is rare that architects consider themselves accomplished. Even after several decades of professional practice, I am still just practicing.

The practice of architecture embraces the unreachable goal of perfection. As a classical pianist, I relate. To perform a work of Bach or Chopin, for example, you have to practice…and practice…and practice. The goal is perfection, but in classical music, is perfection attainable? Consider the odds: Can even the most accomplished concert pianist play a piano sonata consisting of one-million notes and not make a single mistake? And make it beautiful?

In architecture, no matter how great a completed building is, we always think it could be better—should be better. Even when a glorious beam of sunlight gracefully illuminates an art gallery the we successfully designed, we will still judge our work. “Oh, the stone trim should have had a sandblasted finish instead of honed, then the reflection would be a few degrees softer. And the window should be moved over two inches for optimal, blah, blah.” No one cares, but we try and try again to get it right.

A moving target, we must try to learn all the code requirements, whether structural engineering, fire exits, energy compliance, water percolation, or ADA compliance. Such items and hundreds more change constantly as a city plan checker issues yet another addendum. The process has become so convoluted that even the plan checkers themselves do not know the requirements they have drafted.

At times, technology moves at a pace faster than the practice of architecture. With AI, 3D printing, modular, BIM, AR/VR, computational design, robotic fabrication, building performance analysis, etc., we are always learning, or falling short of learning, the latest and greatest in software and equipment.

If each new client, good or bad, was the exact same as the previous, then we could practice our client service skills to perfection. The meetings, presentations, and decision-making processes would become routine, hence being well-practiced and eventually needing no more practicing. But of course every client is different in personality, expectations, experience, and thinking.

Poon Design is a boutique design studio. Each project is custom designed, never a cookie cutter solution. If our work was like Richard Meier’s elegant white structures, then when it comes time to pick a paint color, the choices are white 1 vs. white 2. That’s it. But for our projects, each being unique, the choices are endless, not just the 98 shades of white, but maybe vivid colors, pastels, or earth tones.

Beyond the creative world of design, the practice of architecture also involves the logistics of running an office, e.g., marketing and business development, hiring and staffing, payroll and accounting, insurance and rent, state employer laws, and so on.

So in the end, with each project, with each client, with another year under our belt, with another national design award, we get closer to being accomplished as a professional. But even then, we will all say this is still the “practice of architecture.”

Bruce Lee once said, “Practice makes perfect. After a long time of practicing, our work will become natural, skillful, swift, and steady.” But for architects, such perfection may take a lifetime or longer.