TRIBUTE: MICHAEL GRAVES INSPIRES (1934-2015)

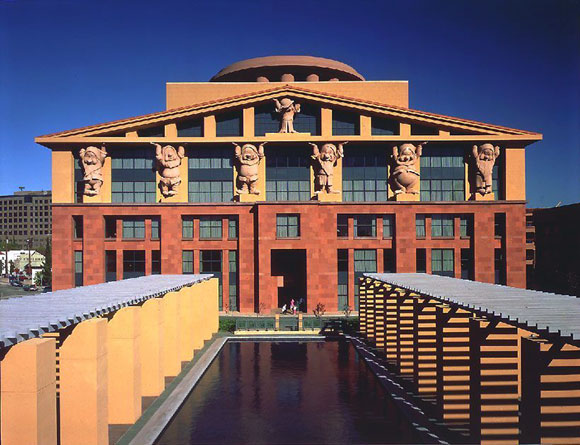

Team Disney Building, Burbank, California, by Michael Graves (photo by MGA&D)

Writing my business plan for Poon Design Inc. decades ago, a small paperback on entrepreneurship suggested that I think about an existing company that might be a model for my future company. The topics at hand were not about the business model, profits, size of staff, or geography—or even design style.

Rather, the topic was about design culture. What kind of design culture did I envision for Poon Design, and what architectural firm inspired me?

The answer was a New Jersey company: Michael Graves Architecture & Design.

My interest did not have anything to do with Michael Grave’s colorful Post Modern buildings with their whimsical motifs and cartoonish proportions. My interest was in what Grave’s entitled “Humanistic Design.”

Graves designed for people. He did not design for headlines and critics, for academic debates, or for personal legacy. Designing for people—sounds obvious, right? It is no easy task to make good on this philosophy, as well as build a culturally impactful, artistically significant, and prolific career around designing in this basic manner. For people.

Graves and his team applied this belief system to every aspect of design, from hotels to houses, from office buildings to toasters, from university research centers to the design of a wheelchair. Sure, many architects believe their repertory is this broad. During his time, Graves was a pioneer in designing without borders.

Late 1980’s, beginning my young adult life in Manhattan, I was a fan of the New York Five. For a national conference with a seminal follow up book, the Museum of Modern Art assembled five architectural voices. All five held a common interest in Modernism and the landmark architecture of Le Corbusier (1887-1965). The five architects became instantly celebrated: Peter Eisenman, Charles Gwathmey, John Hejduk, Richard Meier, and of course, Michael Graves.

Though I was fascinated with the (mostly unbuilt) work of Hejduk (1929-2000), Graves was the individual that I studied, even as he abruptly departed the New York Five. He rejected the Five’s philosophical Modernist common ground. In a heralded crusade on the intellectual battlefields, Graves led a Post Modern movement that was diametrically opposed to the repertory of the New York Five (now Four). Alongside him stood other leaders, such as Robert Venturi and my past employer, Robert Stern,

A new chapter for him, Graves used bright colors instead of stark whites. He used classical elements such as pediments and columns, instead of abstract forms and zero ornamentation. He used humor and wit, instead of severe Bauhaus rationalism.

In the late eighties, I was fortunate to be invited to Graves’ 25th anniversary celebration at Princeton University, where he was the Professor of Architecture Emeritus for 39 years. As a young architect in my twenties, I joined the most influential voices of our industry to honor a man of artistic virtuosity and commitment.

Michael Graves passed away in March of this year. All of us who work in his shadow, are standing in an impressively long shadow.