#67: “WIPE THAT SMIRK OFF YOUR FACE”

Crowds gathering for the public reviews and professor critiques of student project, Wurster Hall, University of California, Berkeley (photo from ced.berkeley.edu)

Late 80’s, College of Environmental Design, University of California, Berkeley. This public review of my studio project concludes my undergraduate studies. The class assignment: design a hypothetical church on the banks of Lake Merritt, Oakland. Analogies of good vs. evil, discussions about faith, designs representing religion, etc. saddled every student’s work.

More than an academic exercise for a mere letter grade, The American Institute of Architects co-sponsored our class, structuring it as a design competition. The winners’ drawings and models would become a public architectural exhibition.

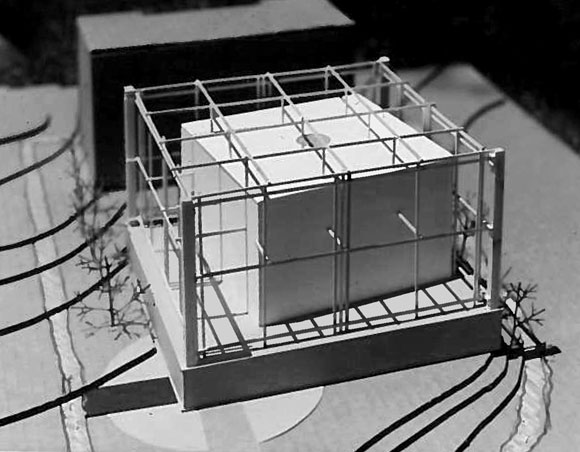

Carefully balanced on two feet, I stood at the front of the class. 40 people in the audience and counting: classmates, faculty, professionals, and members of the AIA. Dauntlessly, I presented my heroic and sardonic church: a boxy concrete temple imprisoned in a giant steel frame, seven stories tall. My artistic composition equated religion to a sanctuary within a constricting cage.

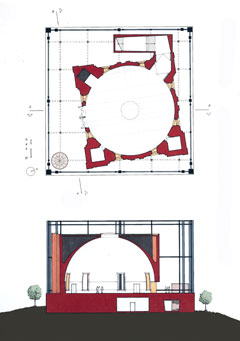

I knew my idea was good. For my drawings, I created a technique that preceded computer generated images. I employed diamond tipped technical pens filled with black Indian ink, drawing on large translucent plastic sheets. On the backside, I applied adhesive color films, each layer surgically cut by hand with an X-Acto No. 11 razor blade, known for its similarity in shape to an actual surgeon’s knife.

Concluding my bold presentation and audacious metaphors, I beamed a self-assured smile.

My professor, Lars Lerup, was already revved up. He lambasted my design, hurling bombastic criticism at my “sad attempt to understand the meaning of architecture and the sublime.” The professor’s assault was both self-servingly theatrical and pretentiously dogmatic. For twenty minutes, not stopping for a single breath, Lerup was clearly on the offensive against a foolish student. As Lerup’s back-up dancers, the faculty seated with my professor propped him up with their complete silence.

Tired from the past sleepless nights, I didn’t mind too much. Perhaps I knew my work was good. Or maybe I just didn’t care because I was soon to graduate.

My professor glared at me for any kind of reaction, any kind of acknowledgement that I was learning at his world class institution. Not responding, I stood there smiling politely. Carefully balanced on two feet.

He would not, could not stand for this, as his shrieking reached an all-time high in melodrama, and an all-time low in appropriateness from an educator towards his student.

The professor shouted, “Anthony, why are you smiling?! I want you to WIPE THAT SMIRK OFF YOUR FACE! Or I will do it for you!!”

Continuing this tirade for a few more minutes, Lerup eventually lost steam against an opponent that was not interested in being his opponent. And then, it was over. I jigged and hopped out of Wurster Hall.

EPILOGUE: The American Institute of Architects selected me as one of the competition winners. I also graduated with High Honors, Magna Cum Laude. As I said, I knew my work was good.

OUTRO: I ran into Lars Lerup in New York a year later, and that my friends was an even more outrageous story. More another day.