#188: THE IMPERFECT FARNSWORTH HOUSE

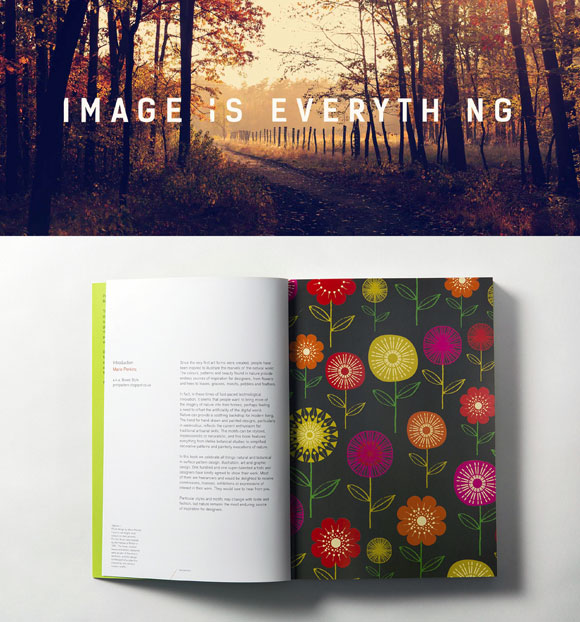

Sitting lightly on the earth. (photo by Anthony Poon)

Considered one of the most iconic houses of Modernism, a masterpiece of the International Style, the Farnsworth House is near perfect. And the imperfections make it more thought-provoking. Finished in 1951, the design from Ludwig Mies van der Rohe has been revered for all its ambition: minimalism and glass walls, connection to nature, groundbreaking engineering, painstaking attention to detail and craft, and of course, “less is more.”

Thousands of books, articles, and university classes have studied this 1,500-square-foot, one-bedroom, weekend retreat. As a freshman at UC Berkeley, my very first assignment was to study this house, then design a hypothetical guest house in the style of. Four decades later, my study continues here.

Client: Dr. Edith Farnsworth (1903-1977)—graduate of literature and zoology, fluent in English, French, German, and Italian, and a concert violinist—attended nearby Northwestern University, only one of four women in her class at medical school. Afterwards, Farnsworth became a successful and wealthy Chicago physician, seeking an architect of greatness for her weekend cottage.

Budget: Back in the 50s, the average construction cost of a home was merely $5,000.00. Though Farnsworth allowed Mies an outrageous budget of $40,000.00, the house costed $74,000.00! Why and how? Many factors contributed to a cost 15 times the average: perfectionist details, costly steel structure (compared to conventional wood framing), expansive glass panels, Roman Travertine, remote location, and so on—not to mention the architect’s requirement for Primavera wood for the cabinetry. At the time, this Central American species was the most expensive wood in the world.

Lawsuit: No surprise. Farnsworth sued Mies for going over budget and malpractice. In turn, Mies sued Farnsworth for unpaid invoices. In the end of a bitter public battle, Mies sort of won and was paid, not a victory worth celebrating.

Flooding: The region is notorious for flooding with water levels reaching over 10 feet. Famous for sitting lightly on the earth, the house floats on its signature steel posts. Raising the structure is a smart countermeasure, but why only 5’-3”—clearly a dimension that is useless during a big flood? Not long ago, catastrophic waters filled up the house like a literal aquarium. The water’s weight and pressure shattered out one of the large panes of glass.

Lighting: I wonder if less is truly more. Within the living areas, there is only one light fixture in the house: the undercabinet strip light over the kitchen counter. Mies designed this first-of-its-kind fixture, now a standard in nearly all kitchens. But the living room has no recessed ceiling lights, dining room has no chandelier, bedroom has no wall sconces, no cove lighting, no floor uplights, no nothing. The architect’s solution to the homeowner: Purchase a floor lamp, and carry that around from room to room, plugging and unplugging into the few floor outlets.

Heat: Though one might think a glass house would not fare well in a cold climate, Mies created an innovative system. Rather than standard floor registers, the ceiling has a barely visible, continuous slot near the top of the glass walls. Running the interior perimeter of the entire house, warm air washes down the windows, countering any outside cold transfer.

Counter: Impressively, Mies designed the longest stainless steel counter at the time. At 17 feet in length, the counter isn’t just a single continuous span; it has a built-in backsplash and integral sink, and has been customized for the cooktop.

Storage: Again, is less more? Is less storage actually better? Though designed as a weekend retreat, the lack of storage could be challenging, even for a patron client of Minimalism. Take the master bathroom for example: no medicine cabinet and below the stone counter, no drawers or cabinets. Where does one put their toothpaste and extra toilet paper?

Infrastructure: Within this most elegant of interiors, where are all the guts of the building: roof drain, electrical panel, water heater, mechanical system, etc.? Within the guest bathroom, the back wall of the shower contains a secret door, and behind it sits the infrastructure. From there, pipes and conduits are gathered into a cylinder, called the “umbilical cord,” that punctures the floor in a single spot, then drops into the earth for connection to county-provided services

Setting: The residence once sat peacefully on 60 acres of lush green nature with a nearby picturesque river. The county made an unfortunate decision to transform a nearby side path into a major road that not only passes uncomfortably close to the house, but is elevated on a slope so that cars view intrusively down upon the structure. Due to this disastrous compromise to the once-idyllic environment, Farnsworth sold the house in 1971 to Lord Peter Palumbo, a British developer and collector of art and architecture.

Today: In 1996, the house opened to the public as a museum, included on the National Register of Historic Places in 2004, listed as a National Historic Landmark in 2006, and currently owned and operated by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. If ever in Chicago, drive to Plano (110 miles round trip) and visit an imperfect stroke of genius.