#178: THE SUPERNATURAL AND JUST PLAIN WEIRD STUFF

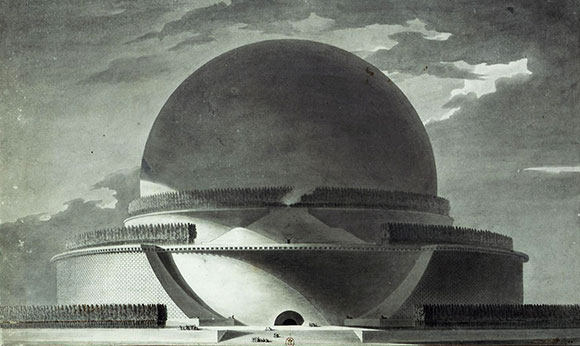

Cenotaph for Newton, by Etienne-Louis Boullée (1784)

A common misconception is that architecture strives to be beautiful. The famed 1st century Roman architect, Virtruvius, did proclaim that architecture must have venustas—the Latin term for “beauty.” But for every Mozart seeking beauty, there is a Beethoven pursuing other qualities—challenging ones even. Indeed, some works of architecture are odd, strange, and even supernatural—if such a word can be used to describe a building.

Merriam-Webster defines supernatural as “relating to God or a god, demigod, spirit, or devil,” and “departing from what is usual . . . to transcend the laws of nature.” Below, I describe a few projects that have peaked my interests, that perhaps relate to a demigod, bucking the rules of the expected.

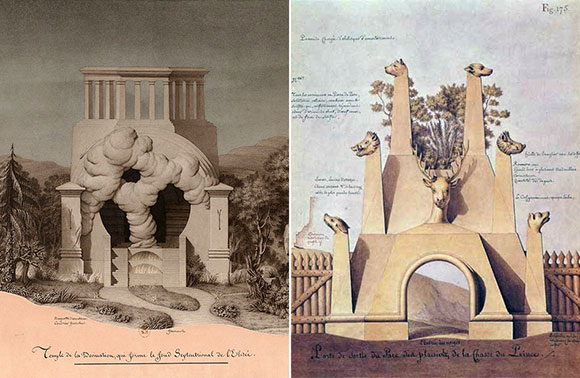

18th century French architect, Jean-Jacques Lequeu—alongside colleagues, Claude-Nicolas Ledoux and Etienne-Louis Boullée—offered peculiar visionary designs that, though never constructed, stoked curiosity. On the left, Lequeu offers a river of fire entering a Greek temple, while honey perfume counters the burning odor. On the right, the design of a hunting gate celebrates the spoils of victory, displaying the heads of the hunted and defeated.

In 2009, artist Henrique Oliveira birthed the Casa dos Leões, a parasitic organ-like visitor within a townhouse in Porto Alegre, Brazil. Oliveira comments, “My works may propose a spatial experience, an aesthetic feeling, a language development and many more nominations to refer to the relation it establishes with the viewer.” Just random words. For me, the message—whatever it may be—is one of uneasiness.

Perhaps it isn’t just the official title: the Steilneset Memorial to the Victims of Witch Trials. Or not just the experiential results designed by artist Louise Bourgeois and architect Peter Zumthor. The eeriness of this 2011 Norwegian project arrives through its thesis: To commemorate the 1621 trial and execution of 91 individuals suspected of witchcraft.

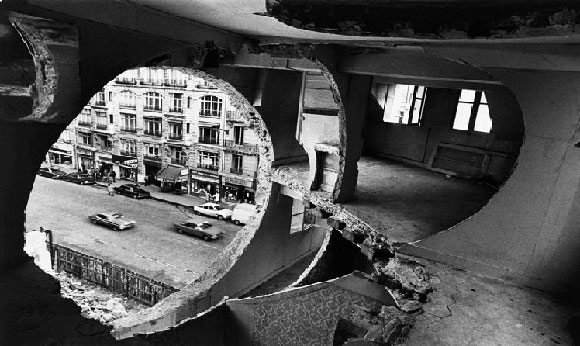

Commenting on the demolition of a building and the destruction of a community, American artist Gordon Matta‐Clark presented an ambitious architectural intervention in 1975. Through excavation and carving, he juxtaposed the history of a location with the recent eviction of the inhabitants—a commentary on memory and powerlessness, origin and futures unclaimed.

Austrian architect and theorist, Adolf Loos, authored this 1903 room of intimacy, luxurious, and whiteness for his wife, Lina. He was 32, and she was 19. The angora sheepskin bed skirt that becomes the floor is sensual even erotic, but also bizarre even creepy.

It’s as if the conventional steel and glass high-rises dissolved away revealing 200 quirky cantilevered apartments, like a residential canyon carved into corporate masses. Located in Amsterdam, the 2022 design of three towers includes apartments, offices, restaurant, and cultural facilities—as well as contradiction and the unconventional.

Petra, the surreal and archaeological city in present-day southern Jordan, holds a rare accolade as one of the Seven Wonders of the World. A town chiseled into the sandstone cliffs, Petra displays the advancements of the Nabataean Arabs, a civilization dating back 2000 years ago. The city was not constructed by traditional building methods of adding materials one on top of another. Rather, Petra was created from cutting and removing stone sections of a mountain—construction through subtraction.

North Carolina-based sculptor, Patrick Dougherty, works with tree branches and twigs as a painter would acrylics and oils. Not just mind-boggling, multi-story bird nests, the projects are temporal like much in nature, intended to make a statement then dissolve and disappear.

Known as the Cave Village of Spain, this southern town comprises whitewashed homes constructed into the surrounding cliffs. The earthly masses hovering over the residences become an omnipotent daily presence to confront, a physical burden to accept. Most would build a city atop a mountain, or within like Petra, but not underneath.

Back to music—adjectives of Mozart’s music might be delightful, lyrical, and exquisite. Whereas for Beethoven: intimidating, discordant, and aggressive. And so it might be with some architecture.