THE ORIGINALITY OF BEING ORIGINAL

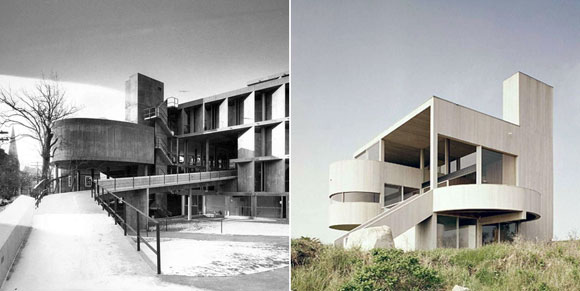

A bold proposal: Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, Los Angeles, California (photo by Lucas Museum of Narrative Art)

In the 2004 film, Garden State, Natalie Portman asks Zach Braff, “You know what I do when I feel completely unoriginal?” She then performs a few awkward dance moves accompanied by shrieking and squealing.

Portman states, “I make a noise, or I do something that no one has ever done before, and then I can feel unique, even if it is only for like, a second.”

She proclaims, “You just witnessed a completely original moment.”

I ask this: Is there such a thing as originality, and is there value to being original?

For the first question, originality is hard to spot. Sometimes we see it and are convinced that we are experiencing something original. Later, we realize that it derivative of something else, or simply part of an evolution of ideas throughout time.

Additionally, two creators could come up with the same original idea. Having done so independently, we still claim that each person’s idea is indeed original.

To the second question, what value is there in being original? Is there purpose to being novel for novelty’s sake, or being unusual simply for being different? For the most part, being forcefully unique in the creative process has little weight. But here and there, that one innovative idea might be the catalyst that ignites a truly original invention from another innovator, artist or genius. In the arc of evolving ideas, I personally assign value to those that seek to be novel if only to do something different.

As unique and bizarre as the examples below are, one might say that they serve no purpose other than to indulge an architect’s whimsical agenda. On the other hand, these examples do no harm (do they?) and again, they might prompt me to challenge my own creative complacency.

Additionally, originality has to do with context. Just because one person experiences something as original, does the creation in question automatically win the label of originality? A tree does make a sound in the forest even if no one is listening. Also, you did have a great vacation even if you forgot to Instagram your photos. Similarly, if an unaware person experiences originality, like a child discovering ice cream for the first time, then so be it.

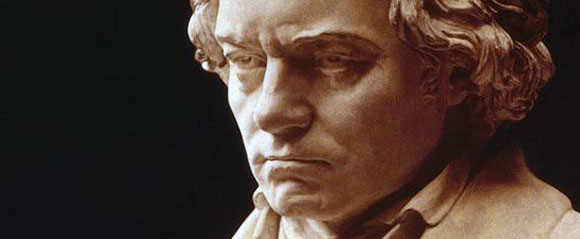

In regards to context and evolution, Beethoven’s third and final period of composing was so original that it left his colleagues far behind in terms of creativity. In such works as Beethoven’s Late Great Piano Sonatas, no one could understand what the mad composer had written, and the result was the breaking of the linear progression of music evolution. Not only did composers leave Beethoven’s third period of work unstudied until decades later, colleagues like Schubert and Schumann chose to pick up where Beethoven left off in his second period. Because they just didn’t understand what the heck was going on in this third period of original music.

Though last year’s The Shape of Water took home the award for Best Picture, I found the movie an unoriginal creation. Fully packed with weary story clichés and formulaic visual devices, critics everywhere complained of similarities of this Oscar-winning film to 1954’s Creature from the Black Lagoon, 1969’s Let Me Hear You Whisper, and 1984’s Splash, just to name a few. Regardless of being unoriginal accompanied by one legal case of plagiarism, The Shape of Water collected three additional Academy Awards with record-setting 13 nominations, alongside box office accolades.

As I work hard to offer innovative ideas to the world, perhaps recognition will arrive at my doorstep if I simply discard the pursuit of originality, and instead copy, imitate or steal. (Not serious, of course.)

(I further studied the idea of uniqueness in design and style with my companion essay, It All Sounds the Same to Me.)