TO BE LOVED

Walt Disney World Swan and Dolphin Resort, Orlando, Florida, by Michael Graves Architecture & Design (photo by James Cornetet, Stringio)

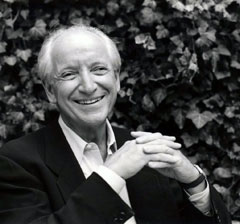

In my last year as an undergrad, the brilliant (to some) Michael Graves gave an evening lecture. As one of the founders of Post Modernism, Graves sparked a movement of creative but tradition-bound architects.

The lecture hall on the UC Berkeley campus was packed; no, over packed. Architecture, art, and even philosophy and history majors plus faculty filled the large auditorium. Alongside filled seats, students littered the aisles and corridors—on the steps, on the floor, wall to wall. Even the entire stage, typically left empty for the dramatic effect of the lecturer at his podium, was covered with eager audience members. This forced Graves to reach the podium by crossing the stage as if it were a minefield.

Which in a way it was.

Delivering a fascinating presentation, Graves entertained with wonderful wit. At one point, he showed a slide of a city downtown, and said disapprovingly, “You can have office towers like these that are black, white or maybe grey.”

Then Graves displayed a slide of his misunderstood but enjoyable 1982 Portland Building in Oregon. He declared with enthusiasm that the freshness of his building lay in the happy shades of yellow, maroon and turquoise. “Or you can also have color!”

The esteemed architect concluded his two-and-a-half hour lecture by unveiling his ongoing design process for a big addition to the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City. The original museum, a brutal mass of a building faced with dark grey granite, presented only one window facing Madison Avenue. For those who support the friendliness of Post Modernism, Marcel Breuer’s 1960’s Whitney was an uninviting and even mean building—the worst of Modernism. (I admit that this building is a personal fave.)

That night, Graves displayed his multitude of designs being developed for the Whitney, each one already rejected by the museum committee. There were so many designs that it seemed to be an excessive, mindless path of creativity.

Was it the architect? Was it the client? Each design iteration was more bizarre than the last. Regardless of whether my young mind could comprehend the architect’s meandering artistic journey, a Post Modern addition to an existing Modern building exhibited the battle between the two artistic movements.

At the end of the epic presentation, the audience was split right down the middle. Some students cheered in support for this courageous architect’s vision. Other students booed his philosophy of architecture.

Graves tried to hold his ground at the podium, but even this senior diplomat could not handle the mix of admiration and disdain. Of love and hatred.

Graves raised his arms to quiet the audience. With tears running down his face, he felt defeat and embarrassment. Silence fell. Despite his stature in the industry, the very mortal designer expressed that night what many an artist must feel again and again, whether in private or in public. Here, he did so in public.

Exhausted of all defense, Michael Graves simply said: “All anyone wants, is to love and be loved.”