#93: PODCAST PART 1: THE ART WITHIN MUSIC AND ARCHITECTURE

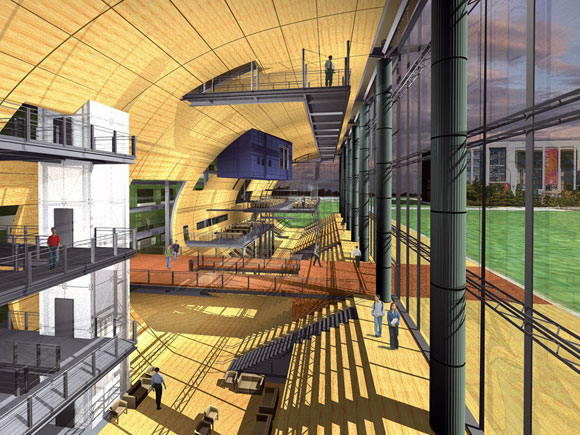

Golf resort hotel villa, California, by Poon Design (rendering by Mike Amaya)

Recently, I had the pleasure of being interviewed on Josh Cooperman’s podcast, Convo By Design. We talked about architecture, art, music, life, and all the things that encompass our creative existence. This is an excerpt.

YouTube clip here. Audio podcast here.

Josh Cooperman: I had the chance to sit with Anthony Poon: author, musician, speaker, artist, teacher, award-winning architect and interior designer. Poon received his bachelor of arts from Berkeley and his master of architecture from Harvard. We talked about architecture, but we also discussed music and art, compared and contrasted these disciplines, and explored ways to incorporate new ideas into traditional applications using nontraditional methods.

I talk to a lot of creative types, and the people that I speak to are really masters of what they do, be it architecture, design, chefs, set decorators, musicians. The point is that everyone I talk to has a creative specialty, but very few have all of them at the same time like you do. So explain this to me. Artist, musician, architect—obviously you’re an architect by trade, but do you enjoy all of these creative pursuits the same?

Anthony Poon: I enjoy all of them. I enjoy them all differently and in similar ways. My passion has always been music and that’s led me to many other things, generating my interests in art, painting, mixed media, and writing too, having recently published my first book.

Josh: Isn’t that a little selfish, taking all of the arts for yourself? Doing everything? Most people can only do one at a time.

Anthony: Well, it is selfish in that it makes me happy. But all of these art forms do require an audience. And I am grateful to have the opportunity to share.

Josh: I have a theory that you have an artistic side and then you have an educational side. By joining the two, you can figure out how to do what you’re trying to do in a systematic way. That you’re limiting the cost of improvisation.

Anthony: I think the thing is this: In architecture and in most arts, there are two components. Architecture has the problem solving component, where you have to figure out the square footage, you have to figure out for the client what the program is, how many bedrooms or how many seats in a restaurant. You have the problem solving of construction costs, of city codes and getting building permits.

On the other hand, completely different, you have the level of artistry, of creativity. Take classical music. Part of the work is learning all the notes on the page. A classical musician can spend years learning one piece, trying to master the flurry of 10,000 notes that fly by in three minutes. That’s not music though. That’s just getting the notes right. After you get to that point, you then have to make it sound beautiful. You then have to add your interpretation, the lyrical aspect that makes it a work of art.

I go back and forth between the problem solving and the pragmatic vs. the poetic and aspirational sides. A building has to be part science in that it can’t fall down. It has to withstand rain. It has to put a roof over your head. But it has to be a little more enlightening than just a structure. It has to be beautiful. It has to make you have a reason to get up every day and go to work, and go to this office building. Or on the weekend, go to the park or go to the museum.

Josh: As you look at your work now, what would you like it to be in 10 or 20 years from now? What is the short term legacy value of what you’re doing right now?

Anthony: The legacy is that, I hope, that my explorations become an inspiration for someone else. I see any artistic endeavor as a constantly moving target, as an evolution, and we’re all only contributing one small step to this evolution. I may work my whole career and only master three buildings that I actually think are worthwhile. Similarly to a musician who says, “Yeah, I’ve composed 500 pieces, but I actually only think these few are great.”

I hope those few pieces that I’ve created are enough for someone to see one day, and it inspires them to move their art process to another level, in another direction, and that’s progress—moving forward. That’s what I call civilization. And that’s what I hope to do.