#48: HALLOWEEN AND ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM

(photo from whitewaydelivers.socialtuna.com)

Halloween costumes are typically representational, not abstract. Costumes are always something—like a princess, pirate or witch. On Halloween, Harry Potters, President Obamas and Katniss Everdeens roam the streets.

But. What about costumes based on abstract concepts? Can one dress up as wonder, rigor or overtime?

As with the Post World War II art movement known as Abstract Expressionism, can Halloween costumes be non-representational? Can costumes be non-thematic, non-literal and non-figurative?

Whereas traditional artists painted water lilies, ballerinas and the crucifixion, Abstract artists painted subjects like color and emotional output or the action of paint drippings. Abstract artists rejected portraying objectified and recognizable classical content.

So I ask: Can trick-n-treaters attempt a similar philosophical position? This could offer entertaining debate when responding to the prerequisite question at a costume party, “Who are you supposed to be?”

Rather than answering Darth Vader, the sexy nurse or Donald Trump, the answer would be complex, because the question is actually “What are you supposed to be?”

Or maybe, “How are you supposed to be?”

The Halloween tradition known as “guising” or going out in public with a disguise, started as early as the 16th century in Scotland, and was first documented in America as 1911. Guising is a design topic as well.

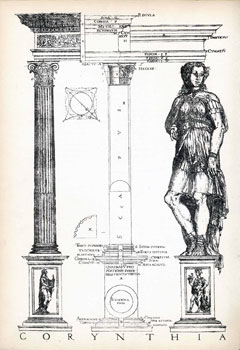

Classical architecture used figurative themes so as to establish rapport with the visitor. For example, the Greek column comprises three components: 1) base, 2) shaft and 3) capital. This composition was intended to reference the human form: 1) feet, 2) body and 3) head.

Modernist architects, many stemming from the seminal Bauhaus period of 1919 to 1932, discarded this idea of representation. Akin to Abstract painters, these architects designed buildings of abstraction and lack of traditional adornment.

As a contemporary example, Pritzker-winner Thom Mayne turned away from Old School theories, such as the 1st century BC Vitruvian rule that architecture must be “firmatas” (strong), “utilitas” (functional) and “venustas” (beautiful).

For Mayne’s 1987 design of the Cedars Cancer Center, he offered a complex vision that was intentionally unsettling. The design is a “tough” building, so as “to instill confidence in patients’ ability to fight the disease,” according to Paul Goldberger, architecture critic for the New York Times.

Besides being a ninja, the Batman, or a zombie from The Walking Dead, I suggest exploring new ideas during the Halloween frenzy. How about going as: the sky or appetite, or maybe frequency or generosity? Hmmm, food for thought.