#173: MODELS AND SUPERMODELS

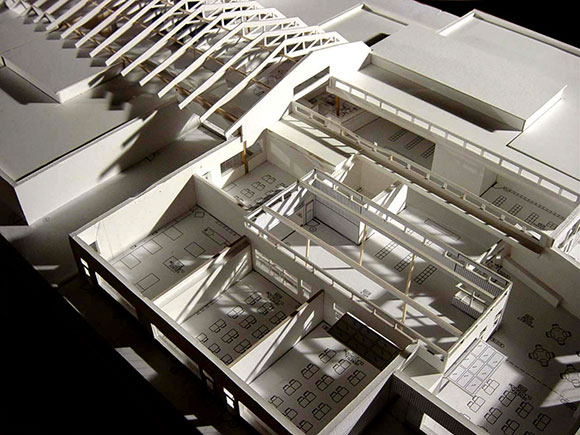

Staples Center and downtown Los Angeles, California – materials: acrylic, lacquer paint, LED lighting, incandescent lighting, fluorescent lighting, and mini-television, by Anthony Poon (w/ NBBJ, photo by John Lodge)

It makes me uneasy when architects replace physical models with computer renderings, replacing a centuries-old craft with software-driven images that pander more to marketing and promotion than exploration and abstract thinking.

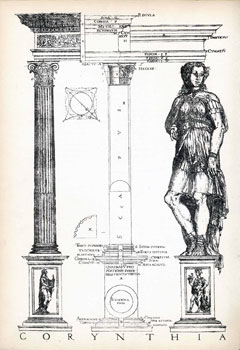

Frank Lloyd Wright’s mother gave her young son the Fröbel blocks, to encourage the inquisitive boy to think three-dimensionally, to create structures like an architect. German educator, Friedrich Fröbel (1782-1852), conceived of a set of wooden cubes, spheres, and cylinders for children to capture their curious need to organize, create, and build. Fröbel proclaimed, “The active and creative, living and life-producing being of each person, reveals itself in the creative instinct of the child. All human education is bound up in the quiet and conscientious nurture of this instinct of activity; and in the ability of the child, true to this instinct, to be active.”

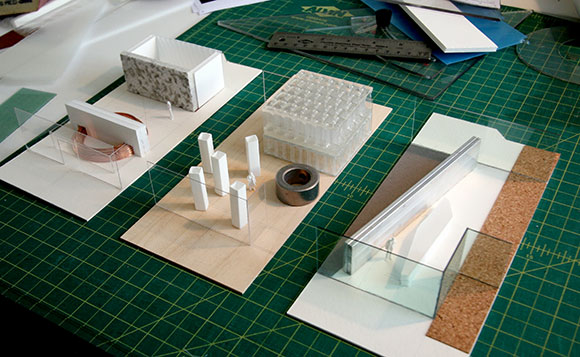

For generations, architects, young and old, engaged in a process of building miniature physical representations of design ideas. Whether Lego or Lincoln Logs as a kid or laser cutting and a 3D printer as a professional, the making of a physical model in scale was inherent in the process of all architects.

I separate “physical model” from today’s “digital model,” the latter meaning a computer file, a virtual three-dimensional object. Digital modeling has reaped tremendous advancements in photorealistic renderings and “fly-throughs.” The sexy presentation drawings provide a client with an image as if standing there looking at the real building.

At times, computer renderers can’t seem to control their self-indulgence as the renderings are over-the-top with multiple light sources, mirror-like reflections on glistening surfaces, over saturation of colors and patterns, perfect skies and sunsets, and supermodels populating the buildings—all resulting in a surrealism that overtakes any substance of the rendering. These exciting images try to show the real thing, but often fail. Renderings should capture the personality and emotion of the space, the story of the design, not a photorealistic replication of materials and surfaces.

There is limited tactile connection in computer processing, other than the clicking of one’s mouse. And architecture, both its process and final product, is tactile and physical. I like feeling how a graphite lead gently wears into the toothy surface of a sheet of vellum. I like scoring a piece of chipboard with an X-Acto No. 11 blade, then carefully bending the chipboard with both hands.

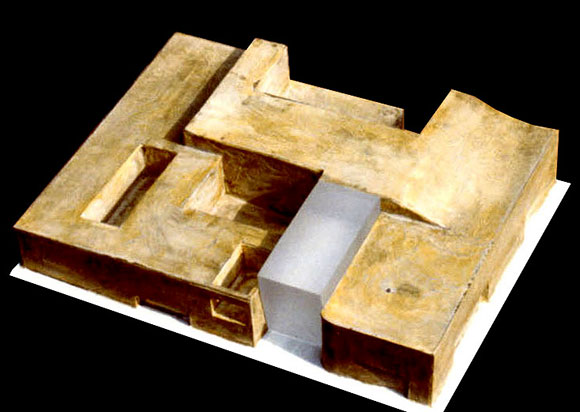

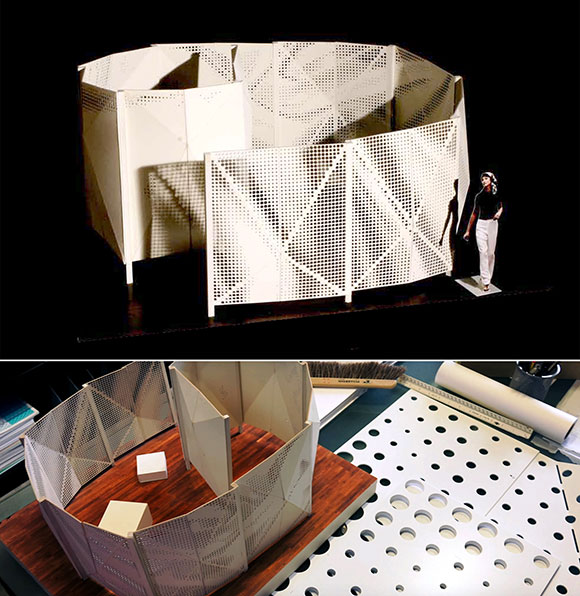

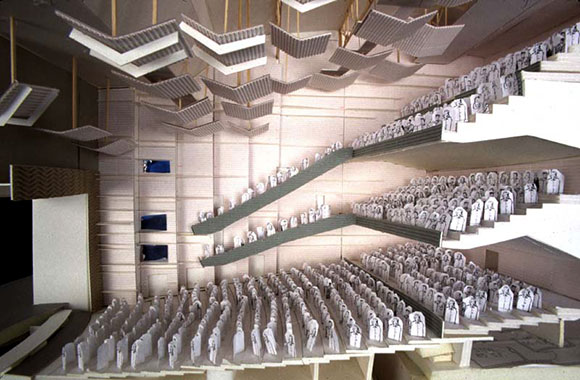

As a physical object, a model is the closest thing to the physical building. But of course, it is a smaller version. But it is through such abstraction that one can comprehend the concepts driving the design. The client can hold a model and study it from infinite angles, or place her eyes, head even, into a large model to experience the space.

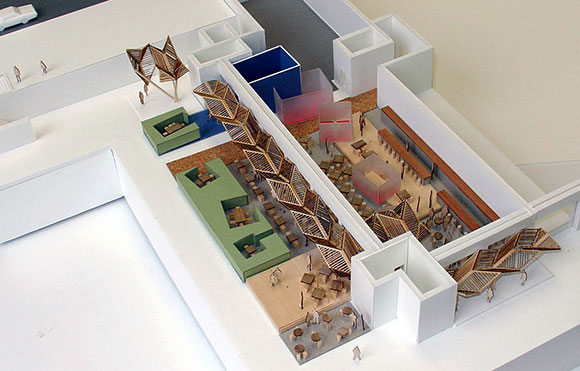

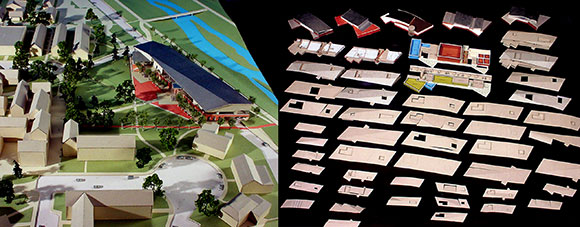

Whether a detailed representational model with little people, cars, and trees, with colors and textures suggesting the actual materials of construction, or a concept model made fast and crude, torn apart and glued back together experimenting ideas that flash into the imagination of the designer—models are an investigative design tool.

Frank Gehry’s process centers around making models with his famed model shop, as does Morphosis with its obsessive use of a large format 3D printer, evidenced by the new book, M3: Modeled Works. This 1,008-page tome focuses exclusively on photos of physical models that span founder Thom Mayne’s career, displayed in reverse chronology, from high tech to low tech model making tools.

Whether architectural models are created with recycled corrugated cardboard and discarded scraps or exotic woods and archival museum-quality materials, the design themes told are can be powerful, poetic even. The thing to keep in mind is that model making is but one tool in the process, as is rendering software, as is A.I. or color pencils.