#160: THE BRAVERY OF HAYDEN TRACT

(W)rapper: Moss' most ambitious project to date, a highrise with a striking exterior frame which eliminates all columns on the inside, Los Angeles, California (photo by Anthony Poon)

Good architecture takes vision. Great architecture takes courage. Within Culver City lies Hayden Tract, a former industrial zone named after the main streets, Hayden Avenue and Hayden Place. For the past four decades, this neighborhood has served as the national stage for the audacious vision of architect Eric Owen Moss and developer/builders Frederick and Laurie Samitaur Smith.

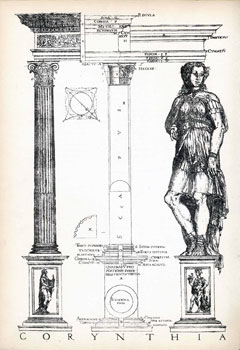

Recently, I got a behind-the-scenes tour of Hayden Tract, organized by the AIA with members of Eric Owen Moss’ studio. Regarding the architecture, the Baroque and Mannerist art movements of 17th and 18th century Europe came to mind: sensual excess, grandeur and daring, and an idiosyncratic sense of awe.

In the 80s, husband-wife, real estate developer team, Frederick and Laura, launched an agenda of city transformation unlike no other. Prior to that, the husband was Pablo Picasso’s assistant, and the wife, a Los Angeles dancer and performing artist. The couple founded their organization, Samitaur, and found their lifelong pet project in Hayden Tract. At the time of their property acquisitions decades ago, the area was not much more than a rag-tag collection of crumbling buildings and streets.

Eric Owen Moss, a Los Angeles native with degrees from UCLA, UC Berkeley, and Harvard, started his design studio in 1973. The three individuals met a decade later through an ordinary circumstance: Moss was a tenant paying rent to his landlord, Samitaur. Since then, Frederick and Laura have been an unwavering loyal client to Moss, commissioning project after project, year after year, decade after decade. This patronage mirrors one of the most fruitful benefactions in history. From the Renaissance, I call it the Medici Effect.

These days, Hayden Tract has become a pilgrimage for architects seeking landmarks of renewal and artistry—a flexing of muscles on the other-side-of-the-tracks. The nearby predictable redevelopment of downtown Culver City brings the expected offerings of shops, bars, and restaurants (and traffic!).

Herbert Muschamp, New York Times, pronounced, “Moss’s projects strike me as such a form of education. The knowing spontaneity of his forms, the hands-on approach implicit in their strong, sculptural contours, the relationship they describe between a city’s vitality and the creative potential of its individuals: these coalesce into tangible lessons about how a city should face its future.”

Neither Modern, Post-Modern, Post-Structuralist, or Deconstructivist, the work of Moss side steps the labels. His architecture defies both lessons learned and the successes of history, paving an individualistic path. The designs also resist the standard definitions of the industry, being architecture and art, sculpture and theater. From the 18th century movement, the Grotesque, such adjectives may apply to Moss’ work: deformed, bizarre, and uncomfortable, yet strikingly beautiful.

The materials are raw and honest, elemental even—unassuming concrete, metal, wood, and glass. The details are extreme. Like a car crash, one cannot advert the gaze, as I wonder how such twisted and decadent details are imagined, engineered, drawn, city-approved, and built in the field. Not only do the personalities of each project— nearly all unique—resist categorization, the forms and shapes appear to disregard even gravity itself. For architects—fans or not of the quixotic collaboration between Moss and Samitaur—the result is an extraordinary city-size amusement park of architectural indulgences, a wonderland of spatial and visual treasures not to be overlooked or presumed arbitrary. I think of the axiom, “Love me or hate me, but don’t ignore me.”