MASSACRE AT HARVARD

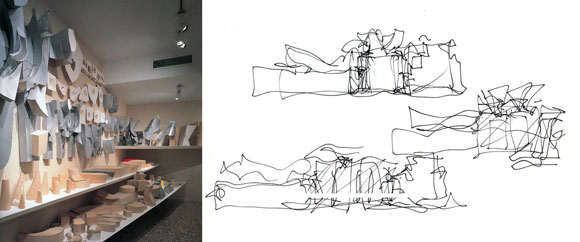

“The Trays,” design studios at the Graduate School of Design, Gund Hall (photo by Kris Snibbe, Harvard University News Office)

I looked up at the packed house, my heart racing.

Students, faculty and interested parties filled the uninspiring concrete theater. Fifty onlookers growing to a hundred. Almost sadistically, the review of our mid-term work at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design is a guaranteed public spectacle. A few stars would be made that day; others might go down in flames.

Down front were my dozen classmates, most of whom hadn’t slept for days, arriving at this event having subsisted for weeks on a diet of cigarettes, coffee, and sugar. The evaluation of our work, an open forum called “crits,” is an event of theatrics, melodrama, and catharsis. There would be no covert submitting of our papers like an English major, at a specified time into some designated box, quietly, secretly.

No, we would each leave this day knowing where we stood, where our future might lie. Everyone else would know too. After each student’s elaborate presentation fueled by months of a creative high, with our drawings pinned to the wall and scale models on a solitary table, with our note cards embellished with the most convincing air of intellectual bullshit, the “jury” begins their critique comprised of praise, appreciation, judgment—and/or ridicule.

The audience was larger than usual, as the professor of my class was a rock star of architecture, coined lamely by the media a “Starchitect,” a man of incomparable intellect, intimidating presence, and literal massiveness of forehead, Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas. (Years later, Koolhaas was awarded the highest honor in the architecture industry, the Pritzker Prize, akin to a Nobel Prize. And yes, his name is Cool House.)

As if that wasn’t enough to ensure a sold-out show, Koolhaas invited his New York colleague, Steven Holl, another impressive force in the field of design. (Holl would go on to be the Gold Medal recipient from The American Institute of Architects.)

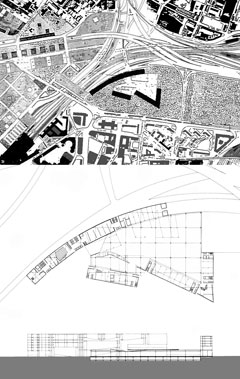

The project assigned to my class was the design of a convention center in Lille, France, at a location that would soon be the continental arrival zone of The Chunnel—an engaging and challenging student project—and a real commission on which Koolhaas was working. When completed, his behemoth project totaling eight million square feet would become known as Euralille, one of the most ambitious architectural statements of the time.

It was my turn to present. I did my best to exude not only confidence but heartfelt belief that my design was the right direction for the project. As a student of the creative arts, I felt emboldened to take a righteous or even moral stance with my thesis.

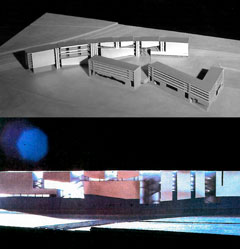

With the size of buildings unlike anything ever conceived, my design would hover over train tracks through some wild fantasy of structural engineering about which I knew nothing. I supplemented my formal presentation of large black-and-white ink drawings with artifacts of my so-called artistic process. As much as professors liked seeing the final product, they also appreciated the evidence of introspective process, such as numerous sketches and crude cardboard models. From drawing to drawing I dashed. Waving my arms, shaking my head in self-affirmation, I spoke about grandeur and ambition.

I concluded. I took a breath. I awaited my public review.

Holl spoke first. “I appreciate the work here, and the background story of how you got from the beginning of the semester to this point.”

He continued, his voice lowered—and I could feel everyone in the fishbowl lean in closer.

“I am sorry, Anthony.” He picked up the small, earliest conceptual paper model. “Maybe you had it right here.’’

Oh shit, I thought.

“I am sorry, but you not only had it right here, you wasted the rest of the semester making your first concept worse, exploring bad ideas, wasting the contributions of your fellow students and your professor . . . and . . . you are wasting our time right now.”

The gasps from the spectators in the coliseum were not only audible, but physical I swear. I looked up. More people were arriving. The word in the hallway must have been that a classic crit massacre was going on. Whispers in the audience had begun even before Holl completed his diatribe. “Anthony’s a failure.” “I thought he was better.” “Let’s see if he will cry.”

Without even the most banal compliment for my effort, without my even being granted the proper allocated time of twenty minutes, Koolhaas stepped in to end it. Out of mercy, I am sure.

“Let’s move on to the next student’s presentation.”

Koolhaas’ blow was so swift that it was neither here nor there; it was just an end to the whole miserable circus of public humiliation. Koolhaas was bored, as so many smart people are when in the presence of the mediocrity of mere mortals.

I picked up my models, gathered up my drawings and sketchbook, and crawled out of the auditorium. I walked out into the early, crisp cold of Cambridge, and ended up at my dimly lit, ground floor, one-bedroom apartment. I let all my work fall to the floor. I fell into my bed, face first.

This is my future. Whether a city hall or a shopping center, architects design in a public forum. Our work is out there for a generation or more, in the glaring eye of acclaim, criticism, and sometimes, mockery.