#186: ANOTHER BAKER’S DOZEN

Broad Beach Residence, Malibu, California (photo by Iwan Baan)

A few years ago, I listed some of my favorite buildings in the city of Los Angeles. Today, I offer another dozen favorites from Southern California, but outside of Los Angeles proper. There are many wonderful works of architecture in our region that to choose only thirteen is impossible. Regardless, here are some in no particular order, from residences to retail, from restaurants to religious to research.

1: The 10,800-square-foot, six-bedroom Broad Beach Residence offers a new form to residential architecture. The triangular composition by Michael Maltzan Architecture starts narrow at the street and expands towards the beach and ocean, maximizing views to the horizon. This martini glass-shape houses two major bedrooms hovering above a courtyard with swimming pool and basketball court, replete with indoor-outdoor enjoyment of the Malibu coast.

2. The old saying goes, “Love me, hate me, but don’t ignore me.” So it is for this Culver City office known as the (W)rapper, by Eric Owen Moss Architects. The 17-story structure has the honor of being 2023’s most written about building. The bizarre steel exoskeleton with its aggressively cantilevered stairs, oddly shaped glazing, and large expanses of solid walls result in a sublime and grotesque presence in a low-lying skyline. The verdict: I admire the courage.

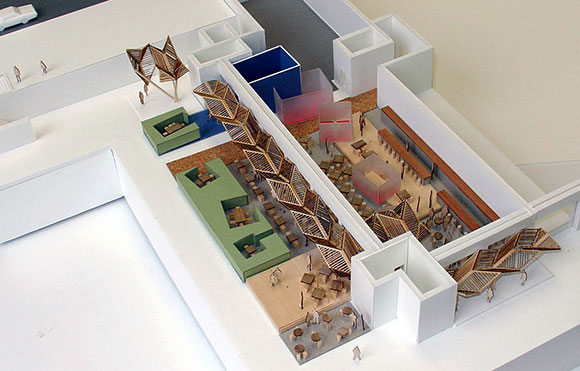

3. In Beverly Hills, OMA reinvents shopping at the Prada Epicenter on Rodeo Drive. From the street, the floor rolls up to the second level, becoming an amphitheater to display fashions or socialize. The traditional storefront display is subverted by eliminating the condition. Instead, the store opens to the street in its entirety—secured at closing by a massive aluminum panel that rises out of the sidewalk. Street retail displays are set in the concrete floor, where a shopper looks downward on, separated by elliptical glass panels upon which one stands, if feeling courageous. Unfortunately, many of the architect’s original ideas did not survive recent renovations.

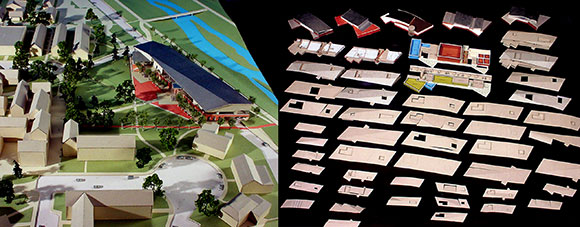

4. MAD Architects—creators of the upcoming, monumental, 300,000-square-foot Lucas Museum of Narrative Art—designed a whimsical mixed-use project of 18 condos and commercial spaces. Entitled Gardenhouse, the architects envisioned a 48,000-square-foot “hillside village” in Beverly Hills, where an assemblage of quirky house-like forms rise from the building’s living façade.

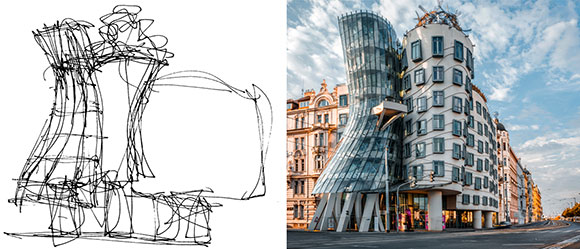

5. During the many decades of its making, the neighbors hated this house. To their astonishment, the masterful creation has become one of the most famous residences in the world, a living thesis of and personal residence to Frank Gehry’s seminal ideas. For the existing Dutch colonial, Santa Monica house, the architect engaged the traditional personality with torn apart walls and roofs revealing a skeletal expression of wood studs. Enter the 1970s premiere of chain link fence, raw plywood, and corrugated metal to the world of high design.

6. Gehry at it again, this time in Venice. Often called the “Binocular Building,” the Chiat/Day headquarters, now occupied by Google, blurs the line between art and architecture. Visitors and cars enter the 75,000-square-foot building through the binoculars, a functional sculpture with offices within, created with artists Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Brugge. On the right sits a tree-like composition in copper panels, and on the left, a contrasting enameled metal ship form.

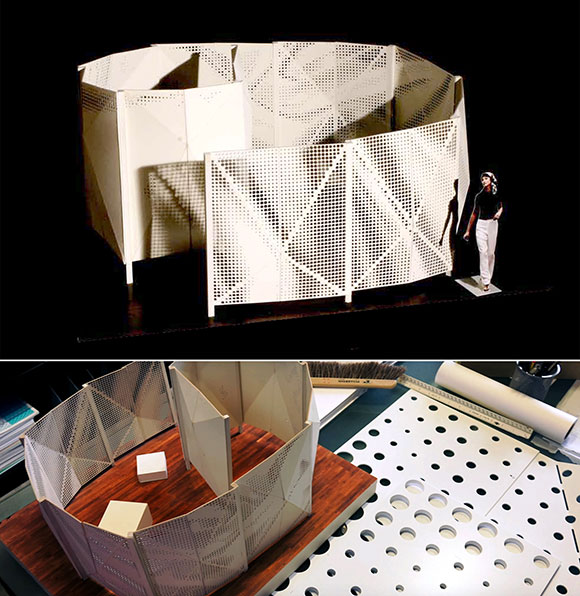

7. Thinking of the Maison Martin Margiela store in Beverly Hills, I am reminded of the Sparkletts water delivery truck and its tiny shimmering discs—a kinetic surface reflecting the sun. Played out on a much larger scale, architects Johnson Marklee covered the Margiela’s façades entirely in these mirror-like discs. Always in motion (and not captured well in a photograph), this visual treat sparkles while displaying wind patterns swooshing down the retail street.

8. Though Kate Mantalini closed in 2014, this Beverly Hills restaurant was an icon, both socially and architecturally. As a place to see-and-be-seen, the design was no quiet backdrop. Architect Morphosis created an energetic living room of art, sculpture, and architecture: angled walls, oculus/skylight sundial, steel beam compositions, curved mural of boxers, striped black and white tile floor, and irreverent giant headshots of Andie MacDowell (why her?). The final result remains in memory as a local attraction and an influential early work from the Pritzker-prized architect.

9. When the Wayfarers Chapel first opened in Rancho Palo Verdes, the 1950s site was not the lush forest of trees as one encounters today. On a bluff overlooking the ocean, Lloyd Wright (son of Frank Lloyd Wright) designed a crystalline glass and wood structure surrounded by majestic skies and vast land. As dramatic as the chapel’s origin was, the current state is no less powerful—now a magical building surrounded by dense trees. One enters as if in a romantic fairy tale. Last year, the chapel was named a National Historic Landmark. (Unfortunately due to recent land movements, the chapel has been slated to be dismantled and reconstructed at a new location TBD.)

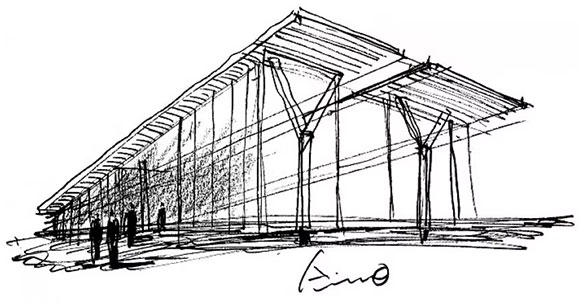

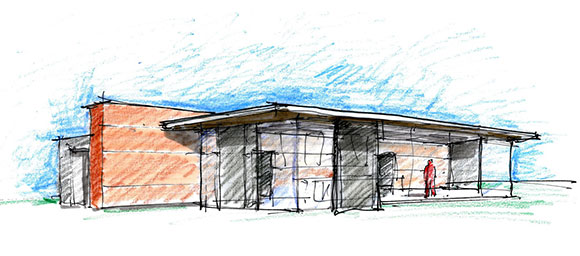

10. A lesser known work from Richard Neutra, the Riviera United Methodist Church displays the simplicity and elegance of colleague Mies van der Rohe’s “less is more.” Neutra introduced the International Style to California, alongside his once-roommate at the famed Kings Road House, Rudolf Schindler—architect of said house (which was no. 14 on this list). Coincidentally in the early 1900s, both Neutra and Schindler arrived from Austria and worked for Frank Lloyd Wright. For this church, Neutra embraced the rectilinear nature of post-and-beam construction, adapting it to the fresh air of Redondo Beach.

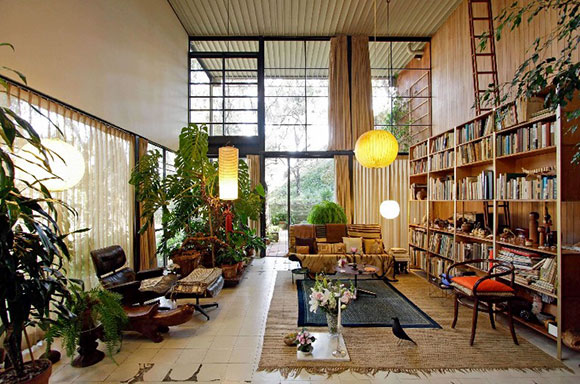

11. The Case Study House No. 8, also the Eames House, served as the modest 1,500-square-foot personal residence and 1,000-square-foot design laboratory for husband-wife architects, Charles and Ray Eames. For this National Historic Landmark in the Pacific Palisades, the house should possess an “unselfconscious” and the “way-it-should-be-ness.” Through new technologies, off-the-shelf materials, and standard components, the architects pioneered much of today’s pre-fab, modular construction industry. (L)

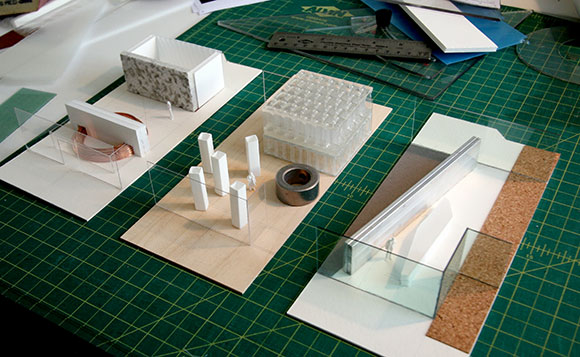

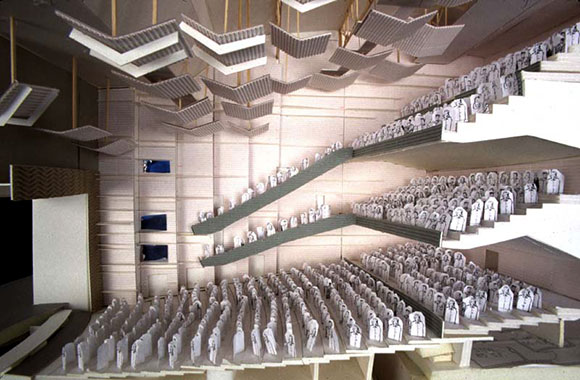

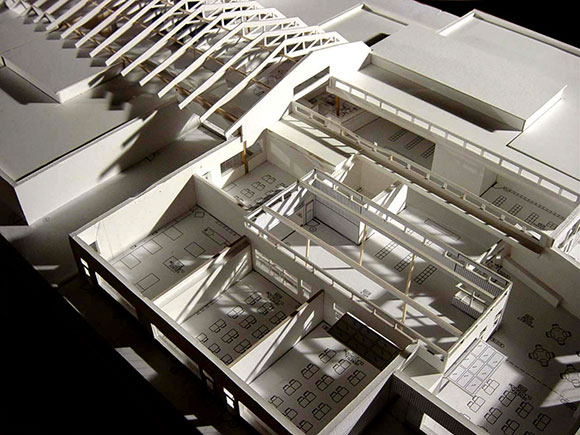

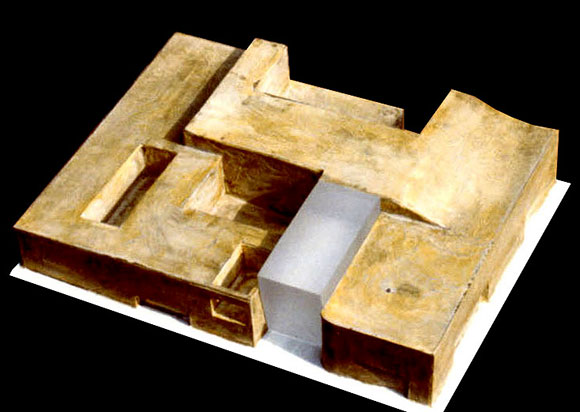

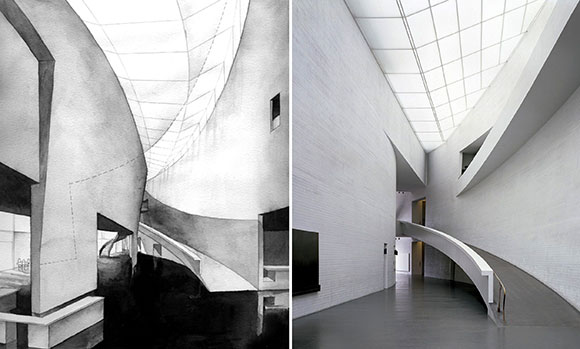

12. With the Neurosciences Institute, Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects created a “monastery for scientists.” In La Jolla, three structures—theory center, 350-seat auditorium, and labs—nestle into the earth and form a courtyard. As is typical of the architects’ work, this research campus explores the most sublime and fetishized (obsessive?) details and materials: sand blasted concrete, redwood panel sun shades, bas-relief surfaces, jade green serpentine stone, fossil stone from Texas, and bead-blasted stainless steel. This tactile environment confronts all the senses.

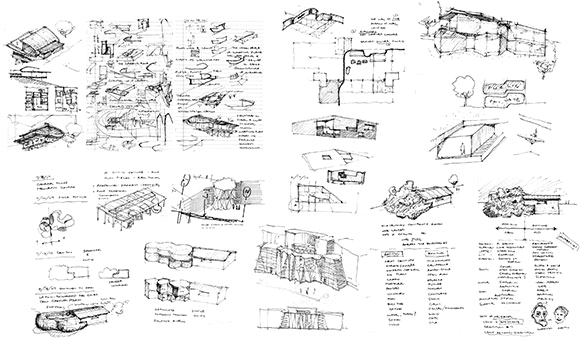

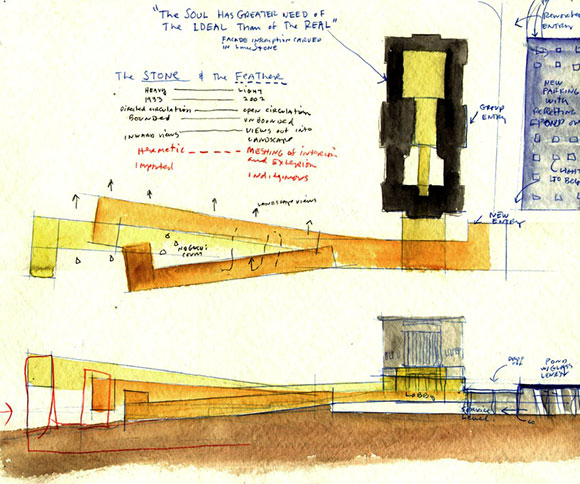

13. Ask any architect, this is the hero of them all: the Salk Institute. If a work can be named one of greatest of all time, Louis Kahn’s 412,000-square-foot research center in La Jolla is high on this list. Jonas Salk, who created the polio vaccine, asked the architect to “create a facility worthy of a visit by Picasso.” With influences from monastery design, Kahn’s profound composition inspires scientists, architects, and everyday visitors, with its otherworldly beauty and axial relationship to the clouds, horizon, and beyond.

(For my 2023 favorites from around the world, visit here.)