#73: PETER ZUMTHOR AND ELEMENTAL IDEAS

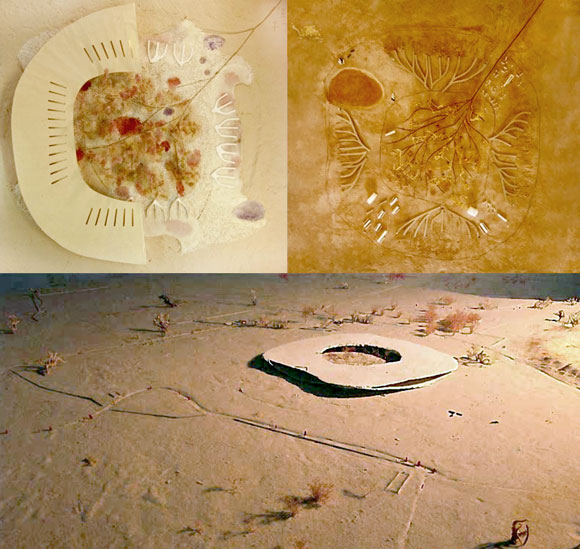

Zumthor’s original 2013 presentation model for LACMA. Though it looks like a conceptual diagram, this is actually the complete design for the project. (photo from inexhibit.com)

There are the usual suspects: Frank Gehry, Rem Koolhaas, Zaha Hadid, I.M. Pei, and so on. Call them celebrity architects or call them “Starchitects,” but one greater walks amongst these mere mortal rock stars. I speak of the one who is called an “architect’s architect.” He is Pritzker-winning, Swiss architect, Peter Zumthor.

Many non-architects may not even know the name of the enigmatic Zumthor, for his Haldenstein-based practice is small and artisanal, perhaps even cultish. But in a short time to come, Los Angeles will know Mr. Zumthor’s work.

upper left: William Pereira (photo by George Carrigues); upper right: Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Architects (photo by Alison Martino); middle left: Albert C. Martin Sr. (photo from thepowerplayermag.com); middle right: Bruce Goff (photo from thepowerplayermag.com); lower left: Rem Koolhaas (photo by Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times); lower right: Renzo Piano (photo by Museum Associates / LACMA)

He has proposed a courageous addition to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (“LACMA”). This museum campus has had a string of prominent designs of their time, from the 1965 concrete structures of William Pereira to the curious 1986 Post Post Modern addition of Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Architects (my previous employer), from the 1994 purchase of the iconic Streamline Modern May Company department store by Albert C. Martin Sr. to the quirky yet poetic 1988 Pavilion for Japanese Art by Bruce Goff, and from the controversial 2004 unbuilt $300 million glass roof from Rem Koolhaas (my previous teacher, here, here and here) to the elegant but underwhelming 2008 and 2010 buildings of Renzo Piano.

Contrasting all this noisy activity, Zumthor’s proposal is so elemental and simplistic that you have to wonder if this is pure genius, or is it a blob of ink that accidentally got turned into the $600 million dollar project?

However, this is how Zumthor excels. He generates ideas like we all did in architecture school or even as a child. Innocently.

Simple ideas come to us all, and if we stay true to our opening statement, then our architecture can result in greatness. But in the real world of client changes, limited budgets, unrealistic schedules, and construction shortcomings, our ideas of greatness are at best compromised. At worst, our ideas drown in a tidal wave of mediocre practicality and code compliance.

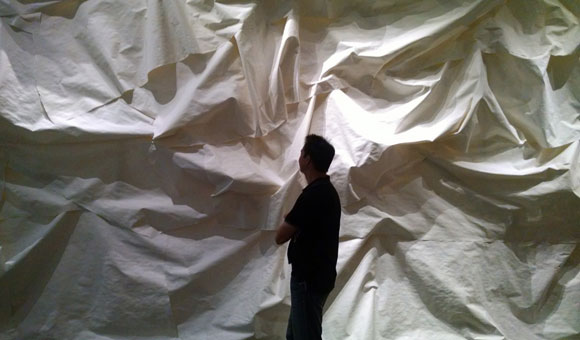

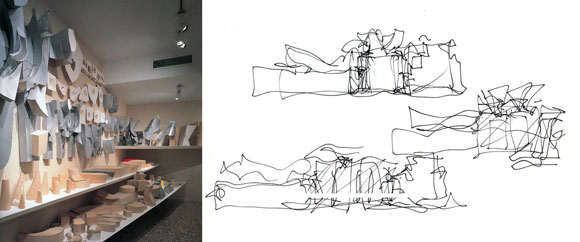

Somehow, project after project, Zumthor keeps his conceptual visions alert and alive from the first day of the design process to the final day of construction. Take for example some of his concepts, such as this one for a hotel in Chile. The presentation appears to be no more than twigs, rocks and debris—literally. Yet , Zumthor addresses the mundane necessities of things like bathroom plumbing and air conditioning, or budget and constructability, and time after time, his final building parallels the essence of his first idea.

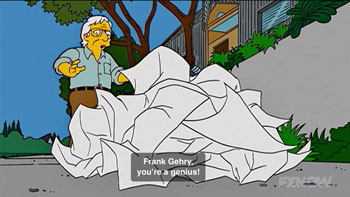

If we common architects delivered such a presentation as the hotel above, in what seems like no more than a teenager’s effort, we would be laughed out of our client’s conference room. The genius of Peter Zumthor is almost Warholian. Not only are the ideas of Zumthor artistic in nature, but he is able to artfully convince a Board of Directors that his ideas are artistic and worth pursuing at all costs. As often critiqued, Andy Warhol’s genius was most profound not in the work, but rather, in how he convinced everyone that he was a genius.

Peers would not take this kind of cynicism with Zumthor. As the media discouraging called Zumthor’s LACMA scheme the “ink blob,” reminiscent of the neighboring La Brea Tar Pits, we had faith in our hero. This architect of poetry and practicality will work in the fire escapes and exit signs, the desert sun beating through the enormous panes of glass, and the structural engineering to bridge over six lanes of traffic on Wilshire Boulevard.

With recent museums in Los Angeles, such as The Broad , the Petersen , the above mentioned Renzo Piano buildings at LACMA, and the in-construction Academy Museum of Motion Pictures also by Piano, each of these projects will look like what happens when talented architects try too hard, yelling like a child for attention. And then, Zumthor walks in the room with grace and calmness.