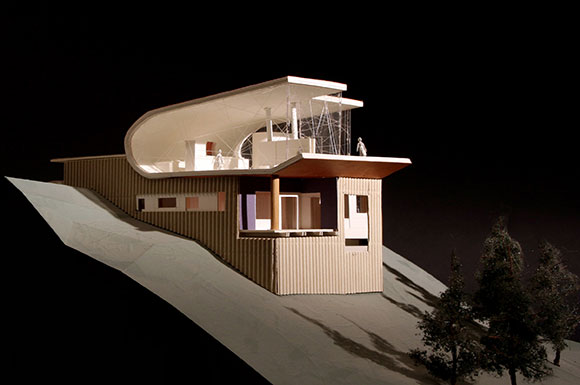

#176: THROWING A CURVE BALL

Absolute World Towers, Ontario, Canada (photo by Tom Arban)

In the good ol’ days of architecture, walls were straight, flat, and perpendicular. With the introduction of drafting triangles, we were excited to draw walls that were angled. But drawing a curve was tricky. Those French curve templates had limits.

With today’s drafting and 3D technology, we can throw a curve ball at the past and explore simple bends, compound curves, organic forms of all shapes and sizes.

For vernacular houses, such as a yurt or igloo, curved surfaces were not an indulgence of the architect’s ego. Rather, common sense coupled with the laws of nature resulted in rounded shapes, wind resistance, structural efficiency and reduction of wasted materials.

Frank Lloyd Wright explored curves, but as pure circles and arcs—meaning, as simple forms limited by the tools of the trade and indifference to the Avant-garde. As graceful as Wright’s Guggenheim museum is, the design is carefully composed compared to the fluidity and excess we see with today’s explorations with curvature.

I remember in architectural school (here and here), teachers of limited imagination associated curvaceous forms with the woman students, stating supposed allegiance to sensual “feminine” shapes. On the other hand, straight lines were hard and masculine, even threatening. For children, a protruding right-angled corner of a coffee table could be literally dangerous, as compared to a voluptuous round table—thought of as maternal even. In 1909, American psychologist Kate Gordon Moore argued, “Curves are in general felt to be more beautiful than straight lines. They are more graceful and pliable, and avoid the harshness of some straight lines.”

Recent brain scan studies have shown how curves in architecture contribute to positive emotional experiences and psychological health and calm. The opposite results: Corners, straight walls and perpendicular lines bring upon a sense of fear, such as with a sharp weapon.

One reason for our allegiance to curved surfaces and forms lies in nature, which contains more curves than straight lines. And the field of Biophilia has demonstrated our instinctive desire for nature and the resulting well-being and happiness. Similarly, the human face—its shapes and forms—contains curves. A joyful smile is one of the most powerful and elemental curve.

Perhaps for centuries, we have favored softer forms—walls that curve, roofs that bend and structures that arc. Thanks to today’s technology, we can explore the curvaceous shapes within our imagination, then represent them on the computer screen or on paper. Technology allows the architect and engineer to develop curvy ideas as virtually implementable in brick and mortar. And it is technology that ultimately allows a builder to construct the curved shapes in reality.

I conclude with Jessica Rabbit and her explanation of her curvaceousness, “I’m not bad. I’m just drawn that way.”