#23: JOURNAL ENTRIES FROM THE LIFE OF DESIGN

View of Los Angeles from my Hollywood Hills house

In designing a house for myself, the process became a diary of sorts. This design journey documented the chapters of my life.

In being my own client and in never actually implementing any construction, each proposed design captured my evolution over the years—from single, young couple, adulthood, married life, baby, to two children. All six design studies below (there are dozens more) addressed domesticity, views of the city, designing for a steep hill, adaptability, and new aesthetic ground.

Over fifteen years ago, I purchased a 1957 tear down in the Hollywood Hills, in an enclave of exclusive homes known as the Bird Streets. The following designs track my existence and evolution.

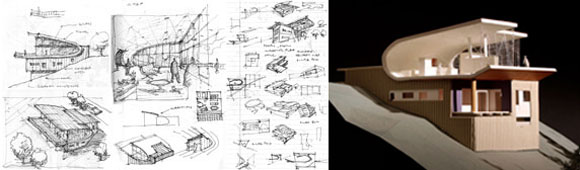

1998. Called the “Wrapping House,” this first scheme explored my joy of entertaining. The iconic loft combined the living room, dining room, kitchen, and other public functions into one space. A continuous walnut plank floor/wall/ceiling wrapped this great room.

2000. Then arrived a design entitled the “Glass Courtyard House.” My interest in hosting extended to the outdoors. A sizable courtyard was the canvas for socializing under the stars. A perimeter of glowing rooms embraced three sides of the exterior space. The open side faced the sparkling city lights below.

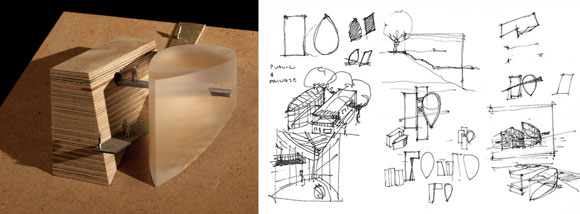

2002. I sought some privacy as I aged, wanting a distinct separation between the general living areas vs. the bedrooms. As I matured, I also chose not to brazenly demolish my Mid-Century house. With a parasitic idea called the “Floating Addition,” I created a polycarbonate and steel structure of bedrooms that hovered over the existing building.

2004. Furthering this notion that I desired both a public social life and a private personal life, the “Public/Private House” explored a home comprised of two abstract shapes. The glass and aluminum public building contained the kitchen, dining room, family room, and living room. The wood clad private building had the bedrooms, bathrooms and art studio. The simplicity of forms signified an agenda to simplify my increasingly busy life.

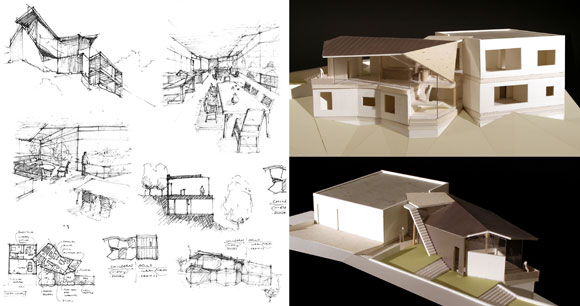

2005. Then came a baby. Two juxtaposed halves composed this “Adult/Child House”: sophisticated and serious for adults vs. whimsical and animated for the child. Luxurious with marble, stainless steel, and dark exotic woods, the adult half was intentionally strict. Playful with exposed ducts, the child half employed novel materials like colored rubber, bright acrylics, and translucent resins.

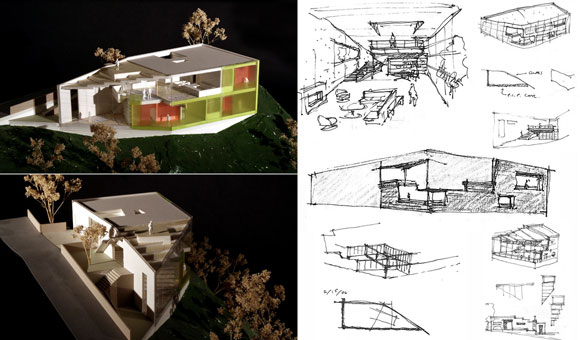

2012. With children, my growing family needed a bigger home, both inside and outside. Simply called “The Point,” I created a geometric house, with a double height rumpus room pointing towards downtown. With my daughters needing an exterior area to play, the rooftop amphitheater provided a zone for the young to imagine, with the surrounding tree tops as audience.

As in life, the creative process is not a closed loop—never a sentence with a period. Design and life are works in progress. They are open-ended acts. Ralph Waldo Emerson acknowledged, “Because the soul is progressive, it never quite repeats itself, but in every act attempts the production of a new and fairer whole.”

2015. None of the above designs were implemented. I sold my property to a developer who has his own plans for a dream estate. In turn, I purchased yet another old house on yet another hillside property. Also with nice views. My design journey starts again.