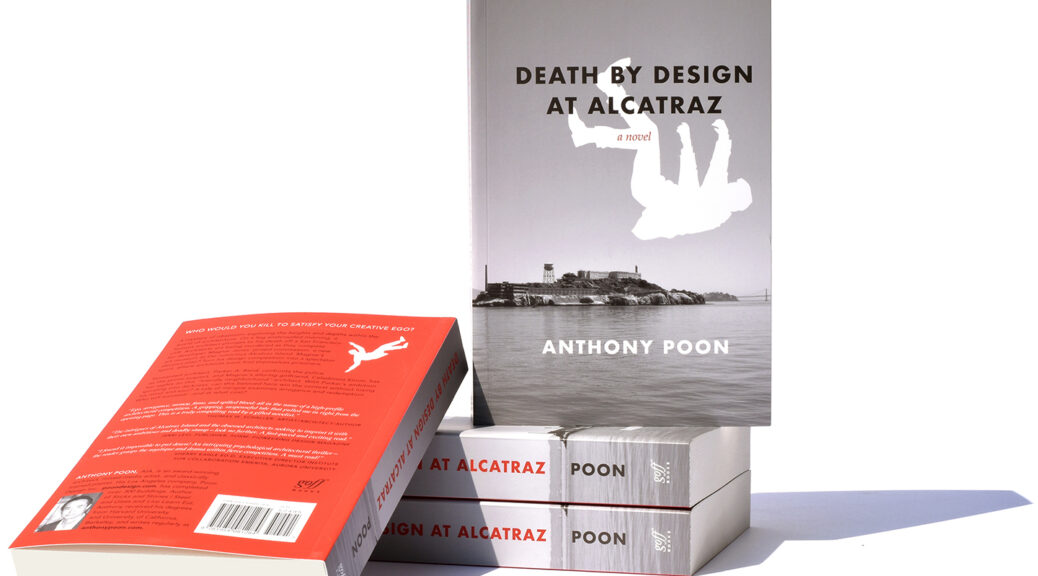

#135: WHO WOULD YOU KILL TO SATISFY YOUR CREATIVE EGO?

Book cover design by Anthony Poon (photo by Anthony Poon)

Here’s the pitch for my debut novel. “San Francisco cloaked in fog and secrets: Architects are being murdered as they compete for a new museum of art at the notorious Alcatraz Island. This mystery of death and intrigue examines ego, arrogance, and redemption within the creative process. Who will win and at what cost?”

Due to the quarantine, there was a slow down at my office. So, I decided to author another book, entitled Death by Design at Alcatraz. For this blog and other outlets, I have written about design, architecture, art, music, and life. I have published two non-fiction books (Live Learn Eat and Sticks and Stones | Steel and Glass), and decided to take a stab at fiction.

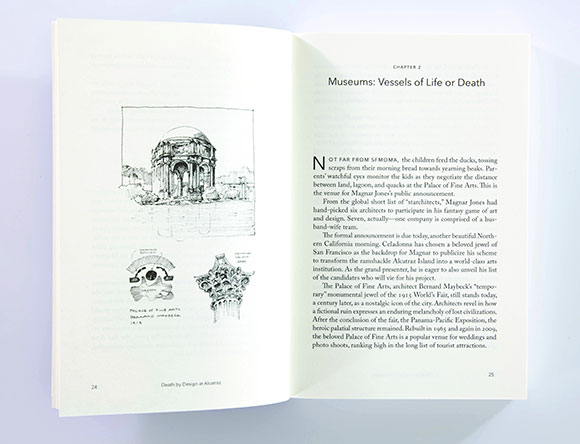

My idea was this: an ‘architectural thriller.’ This 330-page novel with illustrations is a mystery of obsession exploring the heights and depths within the world of architecture. An editor once told me that if I were to try my hand at fiction, it would be best to write what I know. Here are the things I know:

1. San Francisco

2. Architects and clients (good apples and bad apples)

3. Design competitions

4. Ambition and ego

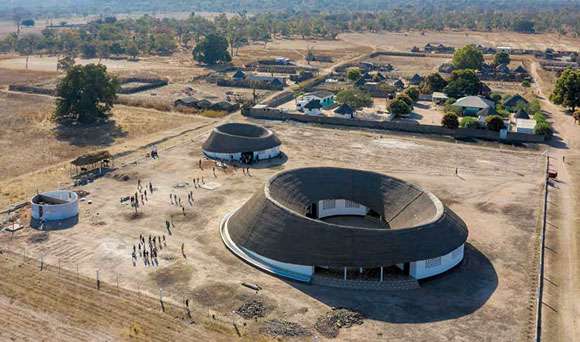

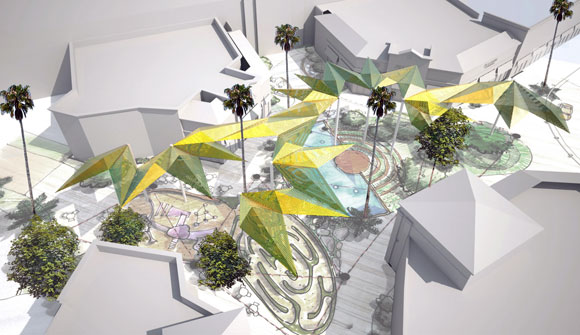

The book summary: On a fog enshrouded morning, a world-famous architect plunges to his death off a cliff. Yet, Magnar Jones, billionaire developer, does not allow death to interfere with his twisted agenda. He still has five architects competing for his prized commission: the redesign of Alcatraz Island, the notorious federal prison, into the World Museum of Abstract Art. Magnar’s devious plan? To turn his design competition into a spectator sport, where architects soon find themselves prisoners. Who will succeed—and at what cost?

The architects in my story are as follows.

– The Neurotic Entrepreneur: university professor and Post Modernist

– The Husband-Wife Team: Ivy League-educated

– The Corporate Jerk: armed with the formulaic resources of a global company

– The British Dame: pseudo-intellectual arrogance and trust funded

– The Mid-Century Modern Fanatic: Los Angeles’ flamboyant designer

– The European Starchitect: dressed in black on black, pretentious master architect

There is also the billionaire Oklahoman Narcissistic Developer Client—vain, egotistical, and talks too much. And of course, his Enigmatic Girlfriend—young “Blondasian” influencer.

Excerpt, “The setting of Alcatraz is both solemn and beguiling. Surrounding the group sits remnants of old buildings, storied concrete carcasses. Cracks on the island’s tough surface show the arcs of beginnings and ends, both life and death. One fissure hiding under broken glass welcomes a tiny struggling patch of grass, a flourishing survivor in a vast surface of ruined asphalt and compacted dirt. Standing guard, the remnants of the taller buildings peer down upon the visitors and demand that the island is respected. Twisted corroded iron bars protrude from beaten stone walls, as if a child’s cow lick that won’t lay flat regardless of the amount of saliva. The counter balance to this, these disparate elements, is the surrounding icy-cold waters that extend until unseen within a silky veil of fog, which on a luminous enough day, provides a cryptic silhouette of the city docks.”

Published by Goff Books, Death by Design at Alcatraz is available at Amazon. Shana Nys Dambrot, Arts Editor, LA Weekly endorses, “The Fountainhead meets Squid Game in this mystery of obsession and murder set in the fancy but cut-throat world of contemporary architecture.”

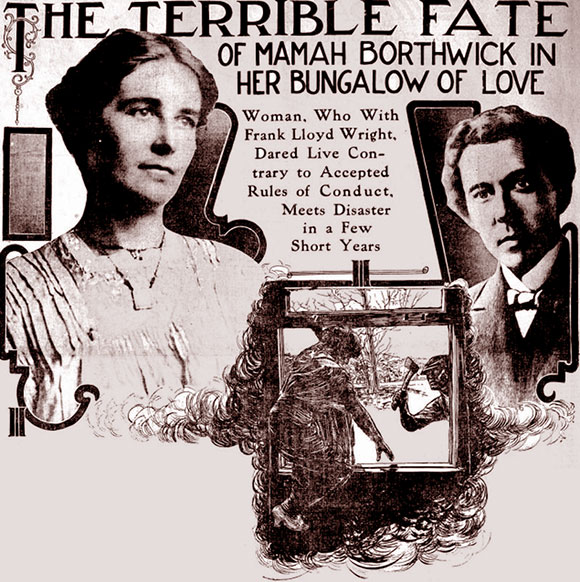

Maybe my next project will be a screenplay about Frank Lloyd Wright. True story: An unfortunate 1914, while Wright was working, his servant set fire to Wright’s Wisconsin residence. The servant bolted all the windows and doors shut. Except for one. As the inhabitants exited through the only escape from the blaze, the servant waited at this open window with an axe. Seven people were brutally murdered, including Wright’s mistress.