#158: LOS ANGELES BAKER’S DOZEN

(photo by Julius Schulman)

As a Los Angeles architect, I am often asked, “What are your favorite buildings in the city?” Considering houses, concert halls, schools, temples—it is difficult to answer. There are so many great works of architecture. To have parameters, I stuck to the City of Los Angeles. I did not include the many treasures in adjacent cities like West Hollywood, Santa Monica, Beverly Hills, etc.. Also, I couldn’t decide on the typical “top ten,” like I have done each year (2019, 2020, and 2021). So in no particular order, here you go: a Baker’s Dozen.

1: In the evening, the John Ferraro Building, commonly known as the LADWP Headquarters, glows like a beacon of downtown. More than a 1960s office building, architect A. C. Martin created an iconic structure metaphoric of the department’s command over water and power. Floating in a massive reflecting pond that hovers over the parking, the building captures one end of the city’s grand axis that aligns the Music Center and Grand Park, and terminating at City Hall.

2: A city-within-a-city, Emerson College by Morphosis offers a collegiate identity unlike anything before. Within 107,000 square feet, two large sinuous structures sit within a ten-story, frame-like building—providing housing for 190 students, educational spaces, production labs, and offices. The technology of computational scripting guided the patterns of the aluminum sunscreens and organic building shapes.

3: Few homes capture the zeitgeist of the Mid-Century Modern movement alongside the family life of the homeowners. Husband and wife design giants, Charles and Ray Eames, created this Case Study House No. 8, simply called the Eames House, to serve as their residence, work space, and design laboratory. The beauty of the architecture stems from the simplicity of form, lightness on the site, and prefabricated materials. Each year, 20,000 design fanatics tour this National Historic Landmark.

4: Rafael Moneo Arquitecto graces the urban landscape with his Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels. Serving as the mother church for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, this design explores a myriad of tilted lines (an avoidance of any right angles), solid concrete walls several feet thick, and the dramatic control of light and shadows—delivering a complex composition of tension/calm, grandeur/intimacy, and mystery/faith.

5: The 1892 landmark Bradbury Building by George Wyman and Sumner Hunt is a classic masterpiece of traditional materials, ornate details, and sun and air. Appearing in numerous works of fiction, movies, television, and music videos, the five-story office building was honored as a National Historic Landmark in 1977, Los Angeles’ oldest landmarked building—today restored to perfection. The skylit atrium—casting intricate shadows of ironwork against surfaces of tile, brick, and terracotta—delivers the beating heart of the building.

6: The existing 1953 Getty Villa—a passable recreation of a 1000 A.D. Roman house—pales in comparison to the 2006 addition by Machado Silvetti. For this museum dedicated to the classical arts, the contemporary renovations and surgical insertions offer a contrasting dialogue of old and new , of history and the future. Like a palimpsest, the layers upon layers of materials, exquisite details upon exquisite details border on excessively articulate, yet reaches the sublime.

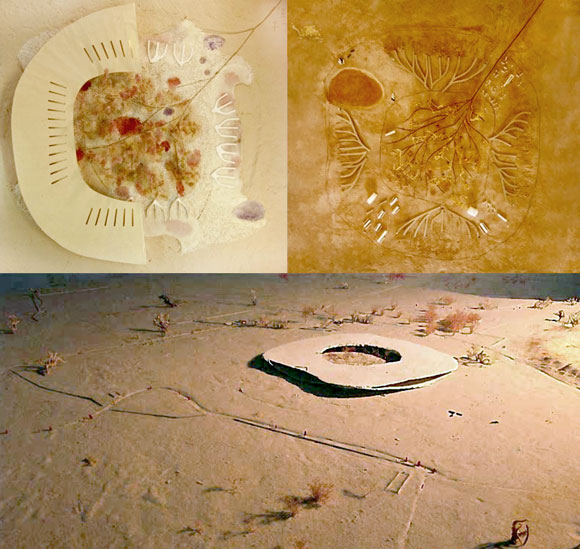

7: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House was the first American work of contemporary design added to the UNESCO World Heritage List. Sometimes referred to as Mayan Revival, the ambitious courtyard house of 1921 comprises an intricate balance of split level floor plates, roof terraces, and steps throughout. The hollyhock—the favorite flower of the owner and oil heiress, Aline Barnsdall—drives the architectural patterns, decorative details, and stained glass windows.

8: Upon completion in 1988, the Pavilion for Japanese Art baffled visitors. The enigmatic 32,000-square-foot building by Bruce Goff—a bizarre combination of sweeping roof forms, cylindrical towers, tusk-like beams, green stucco, and translucent windows—divided critics. Was the work visionary or grotesque? Master architect Peter Zumthor has decided the Pavilion’s worth: His master plan for the campus of LACMA (Los Angeles County Museum of Art), has already demolished nearly all existing structures. Goff’s building will remain.

9: The honeycomb exterior skin of The Broad captivates passersby on this busy downtown street. An instant architectural icon and Instagram-able moment, this three-story museum by Diller Scofidio + Renfro presents a porous wrapper the architects call the “veil”—composed of 2,500 rhomboidal forms of fiberglass-reinforced concrete. Within this “veil” sits the “vault”—the concrete core of the museum housing laboratories, offices, and the massive collections of art not currently on exhibit.

10: The Stahl House, or to many, Case Study House No. 22, is one of the most famous homes in the history of the architecture world. Designed by Pierre Koenig and made known by Julius Shulman, considered the greatest architectural photographer of all time, the soaring hilltop residence made the 2007 AIA list of “America’s Favorite Architecture.” My one criticism is this: The kids have to walk through the master bedroom to get to their two bedrooms. Perhaps an exploration of domesticity?

11. Both a work of art and architecture. Sabato Rodia, Los Angeles’ own Antoni Gaudi, constructed the Watts Towers with few tools and mostly his bare hands. From 1921 to 1954, this Italian immigrant construction worker toyed with concrete, rebar, wire, and tile—even ceramics, seashells, and broken bottles. Recognized with honors over time, the project was designated a National Historic Landmark, and one of only nine folk art sites listed in the National Register of Historic Places in Los Angeles.

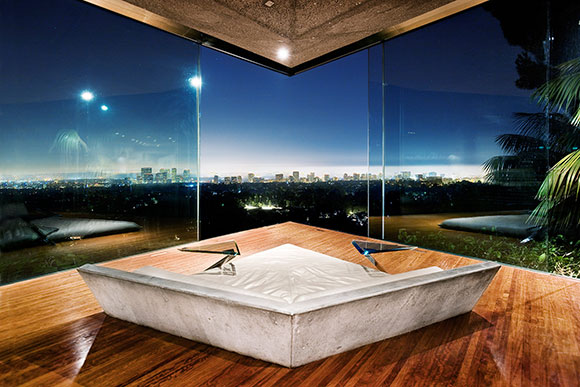

12. A master class in late Mid-Century Modernism, John Lautner gave us the Sheats-Goldstein Residence, a daring home set into the ledge of a sandstone hill. The intimacy of the arrival counters the living room’s explosive embrace with the city view and surrounding nature. The geometry of triangles upon triangles, a revolutionary concrete roof structure, and endless glass walls have captivated pop culture with cameos in films from Charlie’s Angels to The Big Lebowski.

13. No list of local great buildings can exclude Frank Gehry’s almighty Walt Disney Concert Hall. Though the architect had to travel to Bilbao, Spain to prove he is the most famous architect of our time, though the Disney Concert Hall took 15 years to complete and resulted in 300% over budget, the project stands as prominent as the Eiffel Tower, the Louvre, or the Sydney Opera House.

As mentioned, there are so many iconic masterpieces just outside of Los Angeles. Here are half a dozen. And for my favorite buildings of all time, here.