#72: CROSSOVER: FROM ONE TO THE OTHER

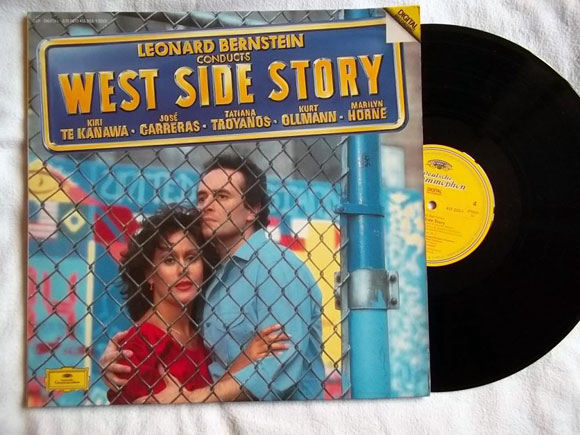

Album cover of 1984’s West Side Story, featuring opera giants, Kiri Te Kanawa and Jose Carreras, instead of Broadway stars Marni Nixon and Jimmy Bryant

In 1984, opera legend Kiri Te Kanawa sought success in an unexpected arena. Courageously stepping into the world of Broadway, she recorded her jazzy version of the 1957 Bernstein and Sondheim musical, West Side Story.

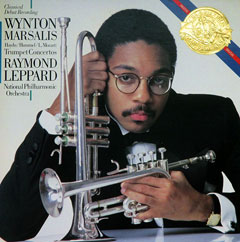

One year prior, jazz great Wynton Marsalis waltzed onto the classical stage with trumpet concertos by Mozart and Haydn—setting aside Marsalis’s New Orleans Dixieland roots.

Whether these two artistic efforts were successful or not, the term “crossover” entered the mainstream lexicon. Te Kanawa and Marsalis crossed over to uncharted universes, creating new sounds and challenges.

Fascinating crossovers continued when Cole Haan combined their leather dress shoes with a Nike athletic sole. With the shout out to the two worlds that have collided, Cole Haan expressed both types of shoes in one intentionally un-unified design.

Crossovers challenge complacency. Critics panned BMW’s 2009 X6 for being a confused crossover. Was it an SUV, a luxury sedan or a wagon? The car performed poorly at all three, thereby not succeeding as a crossover.

In architecture, one version of a crossover is the building type known as mixed-use. As the name implies, this kind of architecture contains a mix of uses—a single project that mixes various functions. What does such a building look like? For a mixed-use design that, for example, houses apartments, corporate spaces, an Apple store, and an art gallery—what should be the building expression and personality? A big house? An office building? A shopping center? A museum?

For one of our mixed-use projects, we designed our building to display each of its components individually, much like the Cole Haan / Nike shoe. Calling our approach the Layered Cake, our University Center comprised four levels—each level expressing a different style of architecture.

On the ground floor, curved limestone volumes with playful windows contain the student retail stores. Consistent with campus standards, red brick wrap the second floor, the cafeteria. The third floor, all contained in sleek corporate-y glass, holds the administrative offices. The student activities and organizations perch themselves on the fourth floor. Clad in zinc shingles, each student club projects out to the campus, cantilevering to get attention.

We continue the exploration of our Layered Cake concept with a project soon to start construction. Our design ideas crosses over between retail, offices, apartments and parking.

Exploring a visually cohesive approach, our mixed-use building in Manhattan Beach weaves together various programs through lines and shapes, such as the folding roof and the folding glass storefront of the ground level commercial spaces. The folding forms capture the recreational culture of a beach town and the graphic quality of ocean waves. In a subtle and playful manner, the folding roof also displays the name of the project “WV,” coined after the name of the client developer.

At the VitraHaus, the various mix of uses are contained in the most common form known in architecture, a gable roof house. Except here, the volumes are not only stretched to strange proportions, but stacked haphazardly one on top of another, offering an unlikely personality. These house-like forms are more than a collision of homes. The various buildings contain retail galleries, arrival spaces, conference center, and restaurant—literally crossing over each other.

A crossover project could also be expressed by expressing nothing in particular, implying no specific functions and thereby is multipurpose. The spaces are flexible and poetic, and unlike the BMW X6 which fails at doing nothing well by trying to do many things, this visitor center in Connecticut succeeds by not trying to do anything at all.