#172: A DAY AND A HALF IN NEW YORK CITY

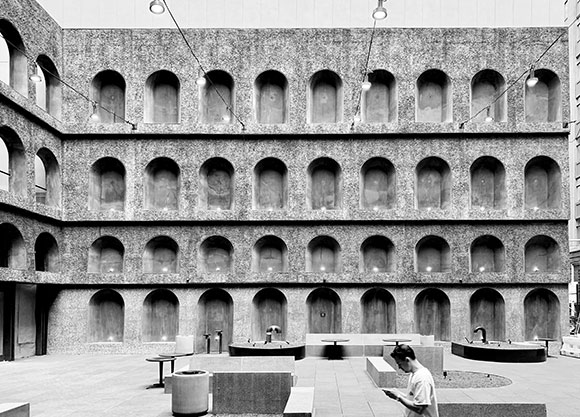

Lobby of 130 William Street (photo by Anthony Poon)

Having wrapped up client meetings in New York City, I had some time to myself. With nothing on the agenda, no one to meet, not much in particular to do, I put on walking shoes to wander this island of Manhattan (here and here). In a day and a half, I visited 20 new architectural works, walking 44,631 steps. Doing the math, that is nearly 20 miles.

THURSDAY

Midtown

11:30 a.m.: I launched from my Times Square hotel, Philippe Starck’s acclaimed Royalton hotel. In the 1980s, Starck renovated this 1898 hotel, his first hotel re-envisioning. This stylish, irreverent renovation propelled Starck onto the global stage of design. Today, some of the ideas have become questionable, e.g., no mirror directly over the bathroom sink?

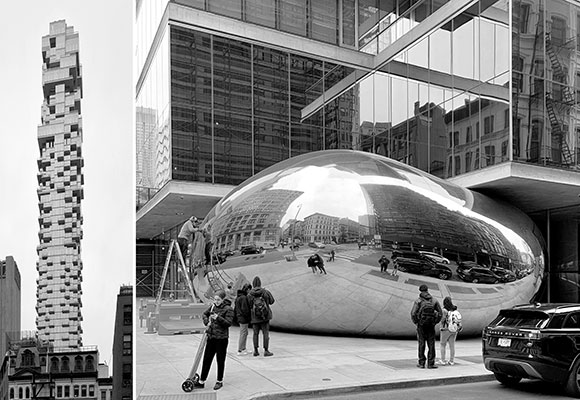

11:52 a.m..: The Steinway Tower displayed optimism and technological/construction advancement, earning the title, the “World’s Skinniest Skyscraper,” designed by SHoP Architects.

12:12 p.m.: Within the famed “Billionaire’s Row” and its collection of “Supertalls,” the Central Park Tower cantilevered (somewhat awkwardly) building masses to grab views of Central Park. Architect AS+GG offered the tallest residential tower in the world, also the 15th tallest building in the world.

12:25 p.m.: How could I not stop into this random find, the Museum of the Dog? I toured an extensive collection of dog-related art, from paintings of presidents’ dogs to porcelain dog statuettes, from an exhibit on the history of the leash to the comprehensive library of books on dogs.

2:02 p.m.: Formerly the AT&T Building completed in 1984, Philip Johnson’s design with its infamous Chippendale crown received both Post-Modernist acclaim and the worst of ridicule. Last year, Norwegian Snohetta offered this new public garden, a wonderful oasis tucked into dense urbanity.

2:29 p.m.: Artist Brian Donnelly, also known as the popular KAWS, blurs fine art and corporate art. Inside this generic corporate lobby, Donnelly installed a work of surrealism and wackiness.

4:31 p.m.: Yoshio Taniguchi’s 2004 redesign of MoMA mined the complexity of many levels, galleries, security points, and city facades to provide a coherently, exquisitely tailored museum.

7:09 p.m.: “When in Rome…” as the saying goes. I visited Times Square’s Hudson Theatre to watch the Tony-nominated performance of Jessica Chastain in Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House. Was the outrage back in 1879 really about a wife merely forging a husband’s signature? Seriously?

FRIDAY

Midtown

9:14 a.m.: I have always enjoyed a modern addition colliding into a traditional building. At the Hearst Tower, Norman Foster added a 40-story steel and glass structure on top of a 1928 Art Deco, limestone, six-story landmark. “Juxtaposition” is an overused word in architecture, but here it is appropriate.

Upper West Side

9:53 a.m.: Certainly to be the next New York architectural icon and tourist mecca, I arrived at the Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation just days before its grand opening. Jeanne Gang authored an oddly beautiful and Grotesque structure inspired by the geologic flow of wind and water—expressed by spray-on structural concrete, akin to that of a swimming pool.

Chelsea

12:02 p.m.: Plenty has been written about the successes (and some failures) of the Highline. But artist Pamela Rosenkranz’s Old Tree caught my eye, a fuchsia-red sculpture standing within the grays and grit of its city backdrop. She questioned what is artificial vs. natural.

2:14 p.m.: Created by Heatherwick Studio, the Vessel heroically rose 16 stories with 150 interconnecting staircases and 80 landings. But after three suicides from the top in one year, the Vessel closed. Today, only the ground level was available to visitors—ending the once-promised Eiffel Tower of Manhattan.

2:36 p.m.: Mere steps from the Vessel sits the kinetic Shed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro. It is rare for architecture to move, yet the retractable shell of steel and fluorine-based plastic opens and closes on eight massive wheels 6 feet in diameter, transforming an outdoor space into a theatrical performance space, event hall, or exhibition space.

3:09 p.m.: A quirky visionary project, entitled Little Island, sits on 132 concrete structures called “tulip pots.” Heatherwick Studio, the same architect for The Vessel, created a 2.5-acre artificial island of rich topography and luxurious greenery, accented by a 687-seat amphitheater.

Lower Manhattan

3:31 p.m.: At the street level of the aptly titled “Jenga Tower,” sculptor Anish Kapoor brought an iteration of his famous “bean” from Chicago. Whereas that city was often called “The Second City” to Manhattan, it is here that Manhattan is second place getting a self-derivative art piece.

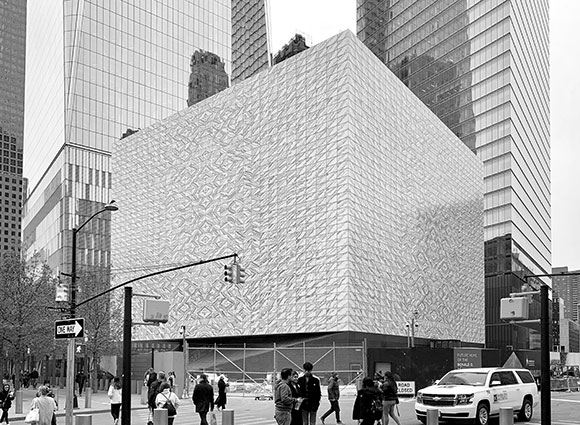

4:35 p.m.: Architect REX’s Perelman Performing Arts Center will, when completed, serve as a hopeful beacon, transforming day to night, from a mute white cube to a glowing marble lantern. The design will complement the World Trade Center, its 9/11 Memorial, and the infamous Oculus, the most excessive subway station.

5:38 p.m.: Speaking of Santiago Calatrava’s Oculus, this architect/engineer brought a second landmark to the area, the St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church & National Shrine. Replacing the original 19th century church destroyed on 9/11, the new Byzantine-inspired building glowed, like the Perelman Center, as a lantern of renewal—through the use of thin slabs of translucent Pentelic marble—the same kind of stone used at the Parthenon in Athens.

6:32 p.m.: Sir David Adjaye’s work is reductive, raw, deceptively simple. This 66-floor luxury condo tower explored arches and arches . . . and even more arches. The darkly-tinted, heavily-textured, hand-cast concrete panels expressed both an enigmatic mystery and somber toughness.

7:00 p.m.: I concluded my NYC tour with a sumptuous meal at Tom Coliccho’s Temple Court restaurant set within the historic 1883 Beekman Hotel. The 2016 renovation of the Romanesque Revival structure, one of the city’s first skyscrapers, restored the splendor of its nine-story atrium.

(I thank John Fontillas, Principal of H3, for his insights into generating this list to play architectural tourist.)