#166: FLATTERY OR THEFT

right: Colline Notre Dame du Haut, Ronchamp, France, by Le Corbusier; left: chapel in Zhengzhou, China (photo rom pinterest.ph, RMJM)

Often, two separate architectural projects by two separate architects appear similar. Sometimes too similar. Hmmm . . . it is simply a coincidence, did one design inspire the other, or has an idea been “appropriated”? In other words, stolen.

In 2011, Lady Gaga released Born This Way, and comparisons to Madonna’s 1989 Express Yourself were swift, exacting, and accusatory. The two songs sounded more than just similar, and Lady Gaga was considered a plagiarist, a common thief. Gaga tried flattery stating that her song was not a copy, but rather, that she was inspired by Madonna—that the work was a tribute to the Queen of Pop.

In architecture, there are many creative overlaps between separate projects which can lead to the legal phrase, “likelihood of confusion.” But often the overlaps are innocent. The zeitgeist of ideas invades the media, websites, and magazine covers. Subconsciously, we design buildings that accidentally conform to pervasive aesthetic themes. But sometimes, there is thievery.

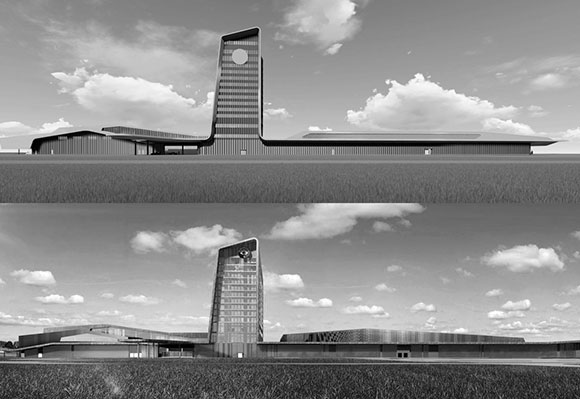

In 2017, Marlon Blackwell Architects (“MBA”), designed the Saracen Casino Resort in Pine Bluff, Arkansas (top image in the above collage). In 2018, HBG Design supposedly “collaborated” with MBA to develop the project. When the client dismissed MBA for unclear reasons, they filed the now infamous 2019 lawsuit. According to Architectural Record’s January 2020 reporting, the suit “claims that HBG has continued to use MBA’s intellectual property without credit or payment, and asks for a judgment of no less than $4.45 million . . . and a declaration indicating MBA’s original authorship of the design.”

MBA won, and HBG’s design (bottom image in the above collage) must now be credited as “an original design by Marlon Blackwell Architects.” Though the financial settlement remains confidential, this victory for the original creator contributes to the ongoing discussion of intellectual property and authorship.

What about Las Vegas producing themed-casinos based on great cities, e.g., Paris, New York (here and here), Venice, and Egypt? What about when an architect in China brazenly reproduces one of the greatest works of the International Style? (See opening image at top.)

For my personal exploration below, admittedly tongue-in-cheek, I mined some of my past designs and found many similar projects by other architects, some explicitly similar. Are they copies or merely independent invention?

As a Harvard graduate student in 1990, I designed this seven-story, vertically-slatted building in downtown Boston (right). In 2015, Stanley Saitowitz (one of my undergraduate professors at UC Berkeley designed this eight-story, vertically-slatted building in downtown San Francisco (left).

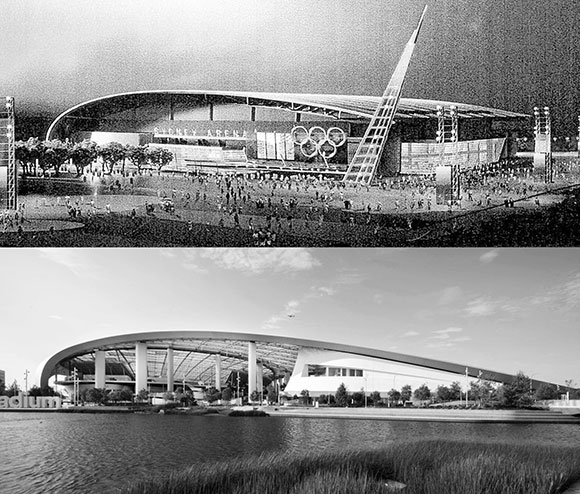

While employed at NBBJ, my design partner, Greg Lombardi, and I designed this sports building for the 2000 Sydney Olympics (top). Our design never got built, but SoFi Stadium opened in 2020 to much fanfare (bottom). Both projects feature an iconic roof curving up from the ground and soaring towards the other side.

As Co-Founder and Design Principal of A4E, I led the team to create this school in Yuba City, California (left)—a design expressing structure, horizontal textures, and a folding roof. Years later after I left the company, A4E designed this Fontana school (right)—a design of similar sentiments.

My studio, Poon Design, designed this 2008 restaurant bar framed by an innovative, back-lit, decoratively-etched mirror composition (left). We won the 2009 International AIA Award, and our design was published extensively. Years later, this store installed a back-lit, decoratively-etched mirror composition (right).

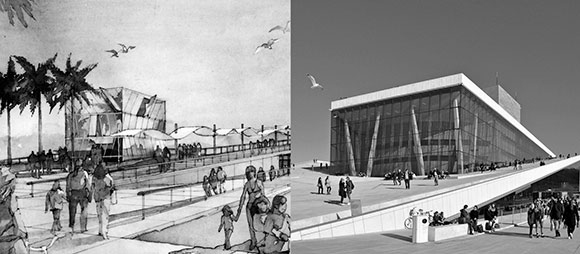

In 1993, Lombardi and I designed this glassy building situated on a plaza that slopes upwards to the sea (left). We won the 1995 AIA Merit Award, and our design was published extensively. In 2008, Norwegian firm, Snohetta, designed this glassy building situated on a plaza that slopes upwards to the sea (right).

Yes, the above commentary possesses some glibness. I understand that we architects sometimes design what is exclusively in our heads and sometimes what is non-exclusively part of a larger dialogue. I accuse no one of plagiarism, but often the resemblances are too striking to ignore.