#153: SOCIAL IRRESPONSIBILITY: SCALE AND OPTICS

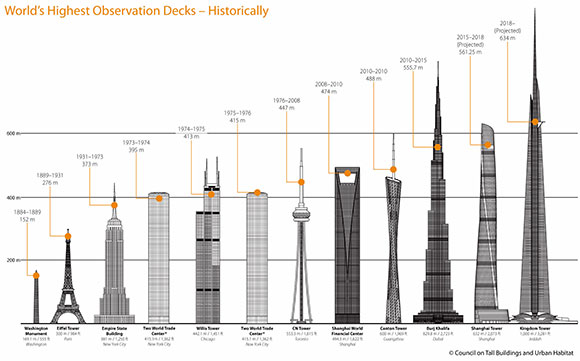

“Supertalls” (photo from sinelab.com)

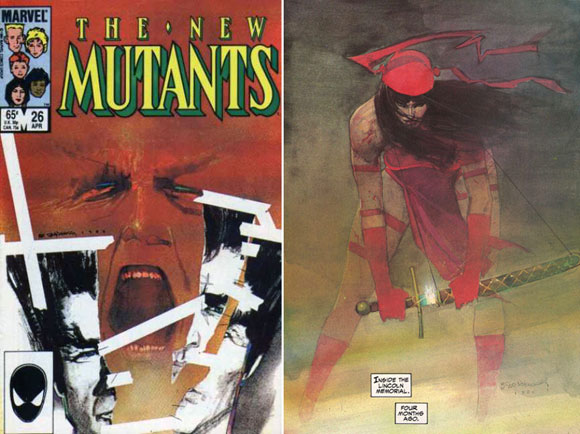

(This essay comprises excerpts from my presentation, The Creative Process and The Ego, on February 18th at Modernism Week 2022, Palm Springs, California. An additional excerpt on ego and arrogance is here.)

The architect’s responsibility to society goes far beyond the state legislature of “protecting the health, safety, and welfare of the public.” Certainly, a design must ensure that a movie theater has the right number of emergency exits, for example. But social responsibility extends far beyond compliance with building codes. Just to name a few topics of accountability: carbon footprint reduction, community engagement, equity and equality, industry diversity, ethical labor practices, philanthropy, resilience, and affordability of housing.

Please heed Stan Lee as he proclaimed, “With great power, there must also come great responsibility!”

When I ponder social responsibility, I also confront social irresponsibility. As I prepared my notes for a presentation for Modernism Week 2022, out of a number of unfortunate examples of imprudence, two come to mind: scale and optics.

First, how tall do we need to build? When the Eiffel Tower was completed in 1887, we reached the limits of our engineering and creative ambitions. At 1,083 feet tall, Eiffel was a marvel and over time, has become one of the most beloved structures in the world. Who knew we would need or want to build taller?

In 1930, the Empire State Building shattered records, completed with a height of 1,454 feet. Over the years since, clients, developers, corporations, engineers, and architects continued an obsession to pierce the sky with vertical and priapic structures. Perhaps, ego and arrogance were the fuel.

Currently, the award of conceit goes to the Kingdom Tower in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Exceeding $1 billion in construction cost, when completed, this literal skyscraper of hotel rooms, residences, and offices will be 3,281 feet tall—three times the height of the Eiffel Tower and more than twice the height of the Empire State building.

The social responsibility of height is not just a numerical indicator. Height is also a concept of scale, meaning responsibility requires architects to understand a building’s height in relationship to its surroundings—whether to be complementary or intentional divisive. The early photo of New York City above displays a red line suggesting a consistent height the buildings, resulting in a cohesive scale and compatibility of neighbors.

The above image depicts NYC today with a similar red line. Half a dozen projects, about 120 to 150 floors tall, counter the scale of the area. Called “Supertalls,” these skyscrapers south of Central Park—mostly residential units serving the super-affluent—pose the questions: Just because we can build this tall, should we? What is the responsibility towards the scale of the existing urban fabric?

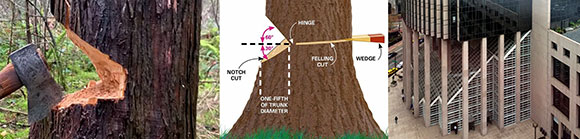

The irresponsibility with optics is evident with the 48-floor office building at 101 California, San Francisco. For the design at the street level—though it is likely that the architect and structural engineer have completed a safe structure, the optics of the sliced bottom with slender columns leaves one to wonder. Is this the responsible and appropriate look for a city known for earthquakes? Does the design idea not remind one of a tree ready to fall?

There are many areas of social responsibility, from low-hanging fruit to visionary ambitions. Architects should not shirk the leverage they hold. With societal precedence having granted architects tremendous influence, let’s not let our creative thinking be impaired by ego and poor decision making.