THE NOISE OF ARCHITECTURE

(photo from jimjenningsarchitecture.com)

I am not referring to the acoustic engineering of a concert hall or the aural quality of a restaurant. Rather, all works of architecture have a certain artistic volume level, from blank mute to in-your-face loud. The visual and experiential clamor of a building can reverberate with a subtle hum, or brash feedback and distortion.

Here I list fifteen projects that represent the dynamic range of architecture’s capacity to blare, starting with silence and increasing to an uproar.

1. If you are wondering where the architecture is, that is exactly the point. The Tidal Pools de Leca da Palmeira intentionally blur the lines between nature and manmade. In so doing, Alvaro Siza (here and here) created a quiet structure for Porto, Portugal.

2. Present though voiceless, Jim Jennings’ Art Pool + Pavilion in Calistoga, California, provides the visitor nothing to relate to. The project is powerfully hush and abstract. (Black and white image above.)

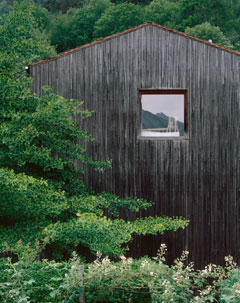

3. Looking like not much more than a barn, rock star architect, Peter Zumthor, delivers a house/office, offering only a single window for scale. Here in Hadlerstein, Switzerland, Zumthor barely speaks and shows off his capacity for restraint.

4. The Benesse House in the Kagawa District of Japan does not need to yell to get your attention. Practicing a meditative Zen-like harmony, Tadao Ando’s (here and here) building is at noiseless peace.

5. What appears to be a typical sacred building starts at first through its name, the “Cardboard Cathedral.” Then it hits you: Shigeru Ban literally used cardboard tubes for this New Zealand project.

6. Like a child’s toy, a cylinder on top of a box comprises the Stockholm Public Library in Sweden. But for Gunnar Asplund, this is no simple toy. The sheer scale and volume makes the building’s presence loud and clear.

7. Wang Shu’s China Academy of Art seems to be contextual with the vernacular of Hangzhou, China. But it is the architect’s details and use of materials in innovative ways that provide this project a slight degree of commotion.

8. For his Experimental House in Muuratsalo, Finland, Alvar Aalto generated an outcry with his brick patterns.

9. Rafael Moneo (here and here) used a cylinder, as did Asplund above. But for Moneo’s Atocha Train Station in Madrid, the crisp brick pillars form a cylinder in an untraditional way. And they resound with a majestic boom.

10. For a housing project cutely entitled “Xanadu,” Taller de Arquitectura (here and here) created something that demands more attention that your generic hillside apartment. In La Manzanera Alicante, Spain, Xanadu may have some items that appear to be normal, like clay tile, gable roofs, painted stucco and residential scale windows—but upon a second look, the overall composition is a hullabaloo.

11. The green, glazed terra cotta, exterior tiles on this addition possesses a visual bark, especially in counterpoint to the traditional original building. In Sarasota, Florida, Macado Silvetti clearly wanted the Center for Asian Art to create a racket when having the new holler to the old.

12. I typical attribute the work of Antonio Gaudi to jazz. His fantastical improvised vision of the world, seen here at Casa Batlo in Barcelona, breaks the rules of composition and color, resulting in an intuitive, lyrical work.

13. The historic collaboration between Chinese artist, Ai Weiwei, and Swiss architects, Herzog & de Meuron (here and here) offered up the 2008 Olympics’ Chinese National Stadium, also known as the famous “Bird’s Nest”. This artistic structure in Beijing blasted onto the world stage with its surreal knitting of massive steel members, alongside the building’s enormous presence.

14. This image of the Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas has not been distorted. Frank Gehry (here, here, here, here and here) designed an interior that has quite an uproar—one that questions if such noise is good for the purpose of this facility, the healthiness of one’s brain.

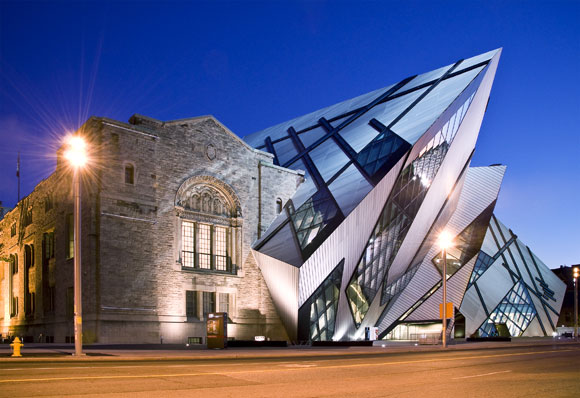

15. Similar to the Center for Asian Art, above, this Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto represents a dialogue between old and new. But here, Studio Libeskind’s (LINK best friends) new addition screams and cries for attention. The juxtaposition fascinates, but does architecture need to bellow like this?