EIGHT THINGS I LIKE ABOUT ARCHITECTURE

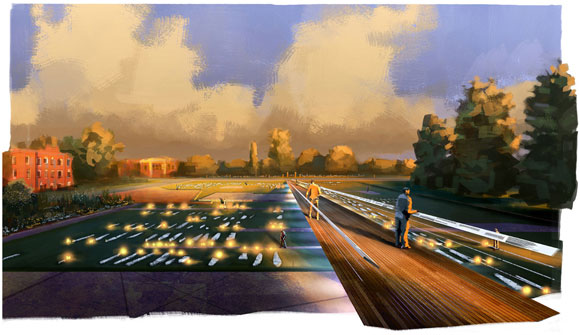

Contraband & Freedmen’s Cemetery and Memorial Park, Alexandria, Virginia, by Poon Design (rendering by Zemplinski)

(This list is a follow up to Eight Things I Dislike about Architecture.)

ONE.

The social importance of what we do. Architects design everything from a retreat home to a veterinarian office, from a homeless shelter to a public school, from a park to a temple. Doctors have been plagued by insurance headaches. Bankers have confronted corruption. Well, lawyers? Not too much new to say there. What fields still have nobility?

TWO.

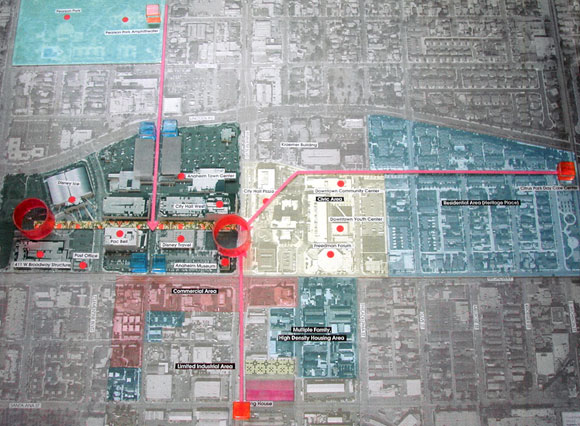

Being creative. Whether problem solving the client’s schedule/budget or envisioning a downtown district, architecture is at the wonderful intersection of art, science and business.

THREE.

Always learning. No matter how long one has been an architect, a new graduate or an expert of 50 years—all architects have new things to learn every day. The field is a challenge, and we love challenges. And we enjoy learning about new clients, new companies, new cities, and new institutions—and building new worlds for them.

FOUR.

The diversity of each day. We go from one interesting project to another. In a matter of months, we will have created several new restaurants. But a performing arts center might take five years. Nonetheless, each project is a unique adventure: having design presentations, finding the right species of wood, coordinating with the electrical engineer, debating with city agencies, sketching in my notebook.

FIVE.

It’s just plain cool to be an architect. Many architects have studied various pursuits alongside architecture: art, literature, photography, history, math, and science—and even real estate, publishing, coding and music. Also, thank you to Hollywood and the likes of Tom Hanks, Michelle Pfeiffer, Ellen Page, Keanu Reeves, Henry Fonda, Wesley Snipes, and so many more, for projecting an exciting image of architects in film. See Celluloid Heroes.

SIX.

The entrepreneurial path. Architects can be a designer at a big company or a sole proprietor, a husband-wife studio or a technology manager. Regardless of role, the journey involves independent thinking, creative contributions, business acumen, and risk taking.

SEVEN.

Rewards. Though the rewards are rarely financial, architects are compensated through the growth of our soul, the smiles and handshakes of clients, participating in the realm of beauty, and embracing each year with worthwhile ambition.

EIGHT.

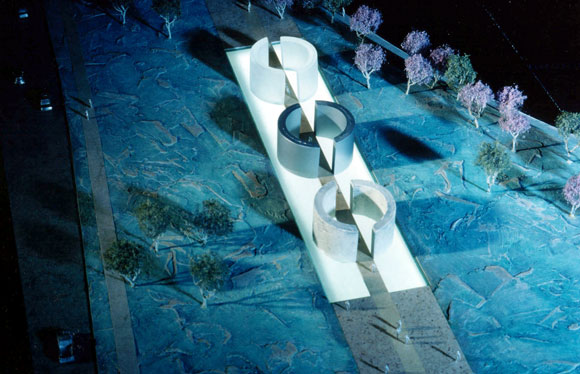

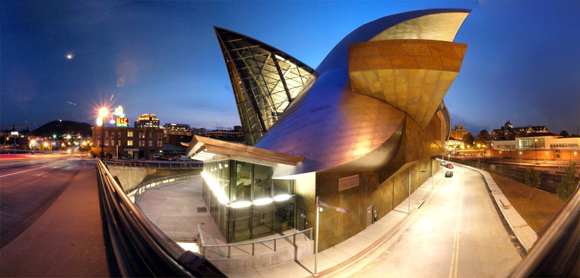

Dreams become reality. One day, we are creating abstract concepts in a sketchbook or Revit. Not much later, concrete is poured, steel is erected, windows are installed, and an architect’s vision is constructed for the world to witness.