#214: IS 85% GOOD ENOUGH?

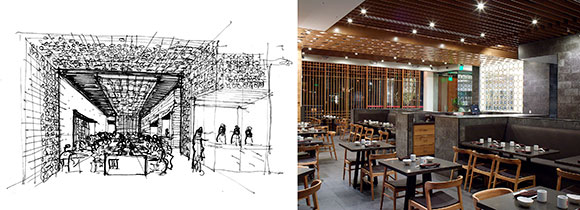

Score: 93%. WV Mixed-Use Project, Manhattan Beach, California, by Poon Design and Steve Lazar (drawing by Anthony Poon, photo by Gregg Segal)

At Poon Design Inc., we evaluate the completion of each project. The question is this: What percentage of the original design is evident in the built work? If we are successful, the final results capture the initial concept, and we pat ourselves on the back for achieving 95% or higher. But sometimes, we get only 70% or lower, meaning the original design got compromised along the way. Why/how?

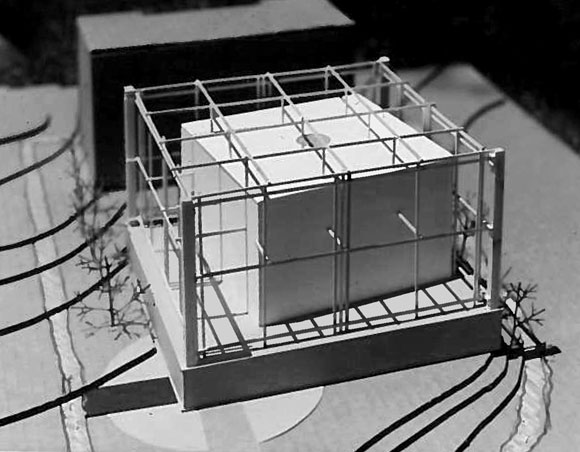

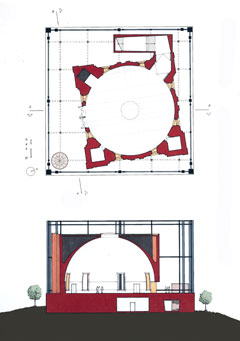

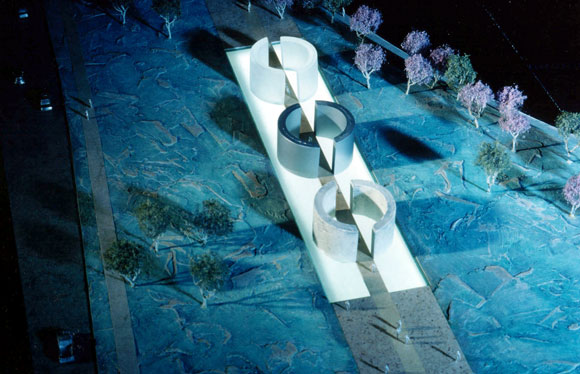

Every new project commences with bold ideas captured in initial sketches, conceptual models, preliminary computer renderings, or even a powerful written statement. All architects have great genius designs in their heads. But keeping alive the spirit of the original thinking can be a challenge over the duration of a project, whether a house, school, or restaurant. During these years in the making—sometimes one, sometimes ten—several influences impact a project as it progresses from the early design work to phases of development, technical refinement, approvals, and construction.

From the start, the architect evaluates the client’s wishes compared to their budget. So many projects begin with an ambitious client program followed by a creative architect vision. When the construction costs arrive, we often find the dollars lacking. In turn, the creative vision gets paired down, or as some colleagues like to say (misleadingly), “value-engineered.”

The realities of a project, such as structural engineering, can also hinder a valiant design. Sure, the architect might envision a museum without columns or a concert hall with a glass roof, but are such things physically possible? Perhaps they are within the laws of science, but at what cost? When reality sets in, the museum ends up with a dozen columns and walls, and the glass concert hall has a conventional metal roof.

All projects go through the city Plan Check process, where the design is examined by various agencies for approval. Often the moving-target city codes can be a damper on a great design. For example, the gourmet restaurant with an open kitchen and big sliding doors to a patio will not be approved by the health department due to flies getting in the kitchen.

If a design survives the above, then comes construction. Will the contractor follow the architect’s drawings? What is the quality of the contractor’s work? Will materials be substituted for inferior ones? Will the client make changes during construction?

Let’s also look in the mirror. Did the architectural team have the know-how and guts to develop a good idea? It’s about courage. Is the architect brave enough? Clients too need some pluck as well as faith. Architects need to earn the trust of the client to pursue the right ideas for the right project.

Poon Design is fortunate to have a few projects score above 90%. 100% is probably an impossibility. The projects that fall short are 50% to 75%. If our average is about 85%, is that good enough? (The project shown here are, or course, ones that have scored on the higher side.)

It takes a tremendous amount of perseverance, tenacity, and dedication to keep one’s ideas alive through the many phases of a project, through the many forces that aim to water down the original thinking. Most architects are perfectionist, so 90% or even 95% might not be good enough.

As the 18th century French philosopher, Voltaire, suggested, “good enough is the enemy of perfection.”