#137: NO BED OF ROSES, PART 1 of 4: PANDEMIC RESPONSE AND THE THREE-LEGGED STOOL

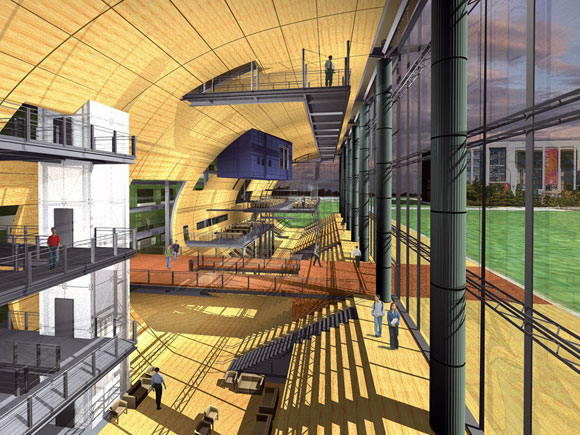

Whitefish River Run, Montana, by Poon Design (rendering by Mike Amaya)

“Host Jeff Haber shares conversations with interesting people from all walks of life, using a positive, uplifting and funny approach,” from the podcast series, No Bed of Roses, brought to you by Kenxus. Edited excerpts below are from the full podcast, episode #1030.

Jeff Haber: Hey there, everyone, from beautiful Fort Collins, Colorado, halfway between Cheyenne in Denver and 5,003 feet above sea level. The dictionary defines architect as a person who designs buildings, and in many cases also supervises their construction. That definition is fine, but barely scratches the surface as you’ll learn from today’s guest.

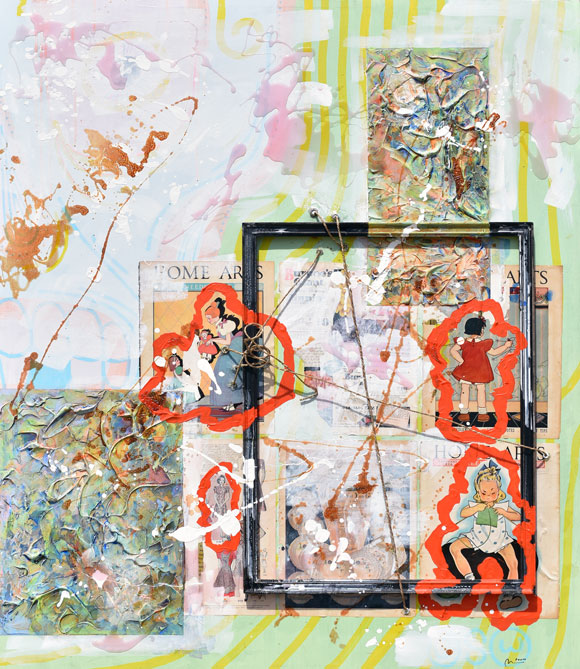

Anthony Poon is an award-winning American classical pianist, mixed-media artist, published author, interior designer, guest lecturer, and oh, yeah, he’s an architect—a really talented one.

Anthony, let’s talk about the pandemic: You work primarily in California, or do you work in other areas as well?

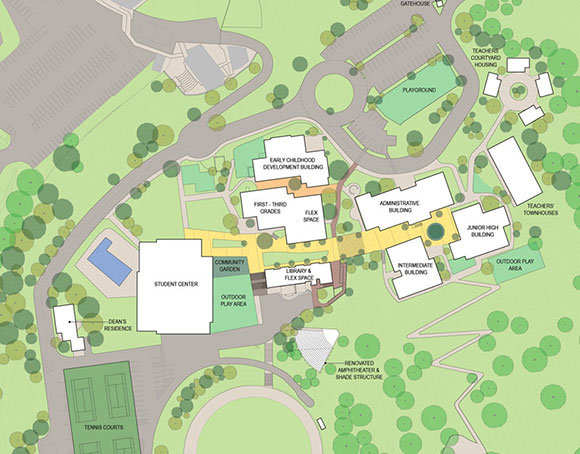

Anthony Poon: Primarily California, but we get our fingers into other locations. I’m also licensed in Virginia and Montana. We’ve also done a lot of work in the Chicago area, and we’ve designed projects as far as Saudi Arabia.

Jeff: How much of an impact has the pandemic had on you currently? And how much of an impact will it have on the way you now go through your design process? How does this make you approach communal spaces?

Anthony: A lot of things that we responded to and changed due to the pandemic—well, a lot of these ideas will stay in place. For example, people have learned that their company teams can work remotely and still be effective. Or, the new views on hygiene and cleanliness should apply into the future, pandemic or not, i.e.: for a school, restaurant, retail, or going into any public space.

I think of one of our clients, a development office in Beverly Hills. We’re asked to redesign their office because they now realize they don’t need to have 100% of their staff back in person. We are looking at a “hotel concept” and micro-offices where there are multiple areas that are shared and used at different points of the day. The office can be smaller in square footage, but still support the same size company or even bigger. Remote connections will stay around, but people will certainly come back together in person and collaborate. Human contact is so important. There’s also so many things we’re learning about mechanical systems, ventilation, and air conditioning. It was a crash course for everyone this last year. We’re not going to throw away that knowledge.

Jeff: What about the use of outdoor space? Is there anything you’re kind of ruminating on?

Anthony: When we talk about outdoor space, I’m thinking two things. One is the smaller scale spaces like that of a restaurant patio. And the other is the concept of public space. I’m talking streets, parks, communal spaces, and plazas.

Generally in California, you’re only allowed outdoor space that’s about half of your interior dining room. Well, that’s obviously changed because of Covid. New ordinances will be created to allow restaurants to keep doing what they are currently doing: have a permanent large outdoor patio. And it can’t be just temporary chairs and tables thrown up. The patio should include ideas like we did at Chaya Downtown where the outdoor dining is as thoroughly designed and detailed as the interior.

Now shifting to the other thing I said, public space. We need to start thinking about cities, say San Francisco or New York. People wonder, are they are coming back at the same density? How do you walk down the street when there’s hundreds of people? Who knows what’s going to happen in terms of distancing? So we need to think about street life and our public spaces, our parks. Certain communities closed down parts of streets for distanced foot traffic. Take Culver City, for example. There’s so much more outdoor dining downtown and public space. They city closed down certain traffic lanes to allow for that to happen. It’s very European, and no one is complaining about traffic and parking. We all still know how to get there, how to get to parking. Point is, we don’t have to design cities, particularly Los Angeles, to be about the car and this automobile street. We should think about the public spaces, pedestrians, where you can enjoy outdoor spaces.

Jeff: Heresy! What this man is saying for the car capital.

Anthony: Blasphemy!

Jeff: It’s not just designing. There’s the business of design. On a weighted basis, is it 50/50 between the creative flow and then client facing and all the ops that you have to deal with? What is that ratio, do you think?

Anthony: First, I would redefine it as a three-legged stool. The ratio is 1/3, 1/3, 1/3.

The first leg is the creative.

The second is the logistics of science and engineering—and things like gravity. So you’ve created a beautiful project, but you still need to make sure it stands up, you still need to figure out the thickness of those concrete walls, and how much steel is being used. You need to coordinate with your structural engineer to make sure it all works.

Now the last third is that of a business, that of an entrepreneur and a business owner. We have to go out there and we have to get work. We have to sign contracts. There are insurance policies. There are things to review with lawyers. There’s billing and making sure you get paid so that you can pay rent salaries. So it is a

Jeff: For any young person considering a career in architecture, any pro tips?

Anthony: Realize that you’re going into architecture for tremendous artistic rewards—that it’s an incredible profession because it is a career based around being creative. But I say ‘artistic rewards’ only because the financial rewards are challenging. It’s a roller coaster ride. You don’t often hear of architects being rich and famous, earning salaries of investment bankers and attorneys. And that’s okay. People go into architecture because it is hard and it is creative, not because they’re looking to be rich and famous.