#152: DESIGNING COMMUNITIES: RISKS AND REWARDS

One of five prototype residences, Saudi Arabia (rendering by Encore)

Architects like to put their stamp on as much as possible, from the design of a chair to the whole house, from a theater to a museum. How about entire neighborhoods? When designing a community of homes, there are risks and rewards. Sure, the ego is stroked to see design ideas implemented across an urban fabric. But there are also pitfalls. Beware.

At Poon Design Inc., we have been fortunate to have designed eight communities from scratch, from California to Montana to Saudi Arabia—totaling over 200 built homes and another 100 on the way.

When designing one residence, there is an overly precious approach, a fetishization of exploring the domesticity of a single client. But when designing a community of over 100 dwellings, the architect now confronts not just the house as a single object, but the relationship between the objects—not just each note of the music, but the connection between the notes.

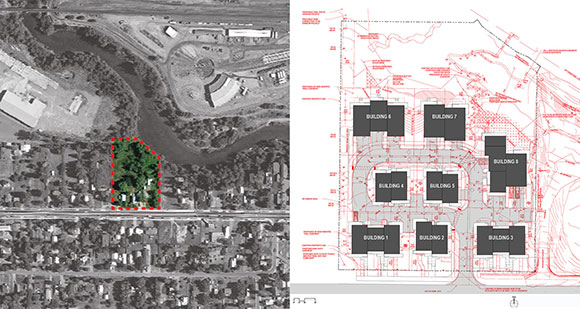

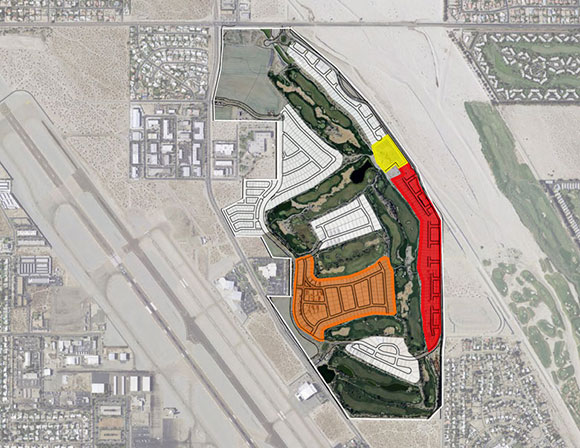

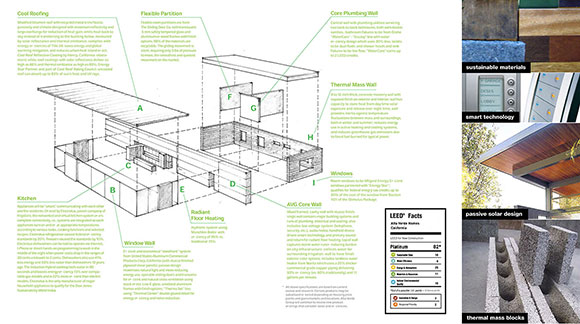

Here, the composition is no longer a single structure, but a body of dozens upon dozens of residences, as well as the open spaces between and around them. Take for example: roads and sidewalks, gardens and entry gates, motor courts and driveways—yes, even a stormwater water management. Designing a neighborhood is creating a place where diverse families intersect, where lifestyles overlap, where utopian ideas are possible. The scale of our work still includes the design of kitchen cabinets and bathroom tile patterns, but it now explores how a fire truck enters the community, puts out a fire, and turns around. We are shaping the land, like a giant given ablank canvas the size of a city.

Some of our projects mentioned above fall into the category of tract housing or mass production housing, meaning that the 40-home community is not a design of 40 unique homes, but rather, a composition of four homes strategically curated to ward off architectural monotony. From a financial standpoint, the four-house-approach allows the developer efficiencies in construction costs and schedule.

For aesthetic variety, unimaginative architects only apply superficial ideas. Yes, you can alter paint color, exterior materials, and landscape. But we do not support the typical tract home methods of adding artificial roof forms, like a fake gable on one and a token trellised porch on another, when both happen to be for the exact same floor plan. No, any modifications must have a reason that is supported by the design concept of that particular house.

Though rewarding and artistically challenging, the big risk with designing entire neighborhoods is frightening yet simple. If you make one mistake, 100 homes have this mistake, so now you have made 100 mistakes. For example, if the roof is not designed appropriately and leaks, now 100 homes probably leak. So have your lawyer and liability insurance ready for a class action lawsuit. In contrast, when designing a single custom house, a problem is usually addressed with a question from the client, then a meeting with the contractor. But with designing entire communities, the architect doesn’t likely know the homeowners who bought these mass produced, spec homes.

In everything ones does, there are risks, and there are rewards. We pick our battles, and we gauge the return on investment. What happens if we fail? What happens if we succeed?